North Adams is one of many small cities across the country that developed alongside, and, in many respects, was built to accommodate, local industry. In the 1950s, North Adams received federal funds that the government dispersed to cities across the country to aid in their adjustment during their difficult transitions into the post-industrial era.

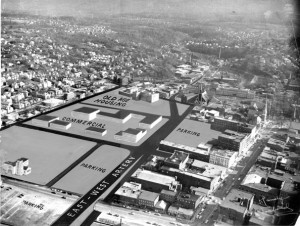

Early plans for urban renewal circa 1950

Under the purview of city government, these funds initiated a series of “urban renewal” projects that were intended to physically restructure the city’s downtown area to better accommodate the perceived needs of the modern resident and consumer. When urban renewal concluded in the 1970s, an astonishing number of downtown buildings and businesses were either demolished or displaced.

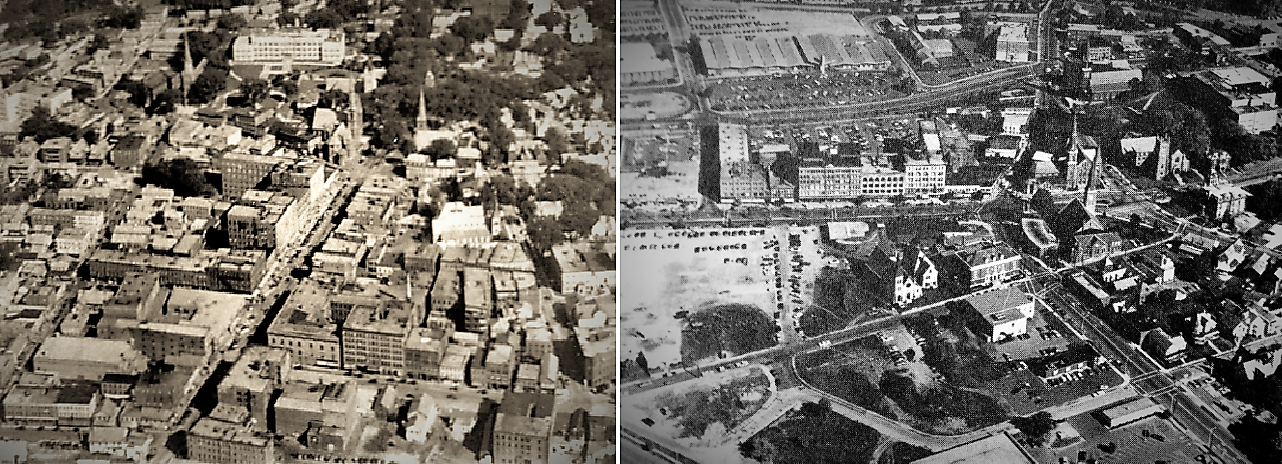

To the left is a part of the 1950 city directory map. To the right is a googlemaps rendering of current downtown North Adams. In the excerpts below, our interviewees cite Main Street, Bank Street, Lincoln Street, Center Street as some of the streets that urban renewal affected most. Demolition during urban renewal made space for the parking lots and big-box retail complexes to the north of Center Street and to the South of Main Street that can be seen in the googlemap.

For residents, urban renewal marked a turning point in North Adams’ history, a watershed moment that affected the city’s architecture, geography, social life, and culture. Billy Perenick portrays North Adams’ various institutions, buildings and businesses as interconnected nodes, securing his sense of place within the community. His interview frames urban renewal’s toll within these contexts. For Perenick, redevelopment displaced people and dislodged important anchors in the local community, affecting people’s connection to the city and community.

Urban renewal came in and they had, 1950s, they tore down the old Saint Anthony’s church. And they built a new Saint Anthony’s church over on Holden Street, next to the… Grand Army Hall. And right there there was a big tree in front, I would never forget, there was a horse chestnut tree and it’s gone. You know, I hated to see that go because where are you going to find a hundred-year-old tree in downtown North Adams? And the Saint Anthony’s church was there… then they had that urban renewal, they tore down Lincoln Street and all those people had to be moved to different areas in town…There was a place over there called….Clark family in town, two brothers, one was a schoolteacher, the other one ran the laundry, that was, you’d bring your linen there, they took care of the hospital, the motels or hotels, no motels- well, whatever they took care of. And that was in that urban renewal project, Lincoln Street that was all gone…that was an area that everybody missed.

These pictures provide a sense for the sheer scale of demolition that occurred within the renewal period. Pre-urban renewal circa 1940s on left, post-urban renewal circa 1980 on right. Note that in left-hand picture, Main St runs west to east from bottom-left to middle-center, while in the picture to the right, Main Street emerges from the left-middle and cuts across horizontally to the east.

Judith McConnell also has vivid memories of the “booming community” of downtown businesses before redevelopment.

And then coming down Eagle Street, there were shoe stores and, it was a booming community. I mean there were all

kinds of, there was an army and navy store where the pizza house is, and all stores all the way down. Riseberg’s dress shop. And across that little narrow Eagle Street there were all kinds of ladies’ shops and where we used to get our gowns for the proms. And then even on Main Street the side that’s all wiped out, there was a stationary store, there was Pizzi’s right on the corner, which was a nice ladies’ store…. I mean there was restaurants and banks and the banks were all marble that when you went inside the tellers’ windows and floors, everything was all marble… And that was an empty hole for like, over 10 years. We used to set up a carnival there, so it was pretty bleak for a long time.

In the excerpt below, Perenick recalls Bank Street. The North Adams Transcript was originally located on Bank Street, and where Bank Street intersected with Main Street stood the city’s most venerable banks (such as North Adams Savings and Trust, First Agricultural), which many of our interviewees consider some of Main Street’s most beautiful buildings.

there was electric company office, there was a hat man there that used to form and shape hats, steam hats, you don’t see that anymore, he’s gone. There was the cobbler shop in there, a little small diner, there was a thriving, one-way street like a European street. They didn’t have cobblestones but there was only room for one car, and you know, if you got too close to the curb… you stayed next to the building! Now that was all gone.

Many of our interviewees mention the banks, the hat store and the small diner [Delaigo’s]. The beautiful buildings and the success of the businesses that occupied them continue to hold prominent places in people’s memories of pre-renewal downtown and suggest that urban renewal displaced not only people and businesses, but also affected their sense of familiarity and their connection with the area.

To the left, Bank Street facing northward to Main Street circa 1968. To the right, the same view today.

Furthermore, Perenick’s comment regarding how narrow roads may have inconvenienced drivers, which the picture above illustrates well, highlights a potential justification for urban renewal. Many of the streets were similarly built, and many of the buildings were crowded together, as the construction of downtown largely occurred during the latter half of the 19th century. In conjunction with downtown’s outdated layout, the poor condition of the buildings and the high cost of repairs likely made demolition seem much for viable to local government. Justyna Carlson, who now works with the city’s historical society and historical commission, states that Bank Street and the south side of Main, was in need of a lot of, of work. And people just weren’t going to be living there anymore. She recalls an anecdote from someone whose father worked demolition during renewal that suggests some demolition was likely unavoidable. At the same time, however, sturdy and often magnificent buildings, were demolished alongside their dilapidated neighbors.

a great deal of that side [south] of Main Street was facades, and once you went beyond what you saw, it went to the back, where you had a beautiful…granite bank building on the front, the back was wood. They were fire traps, there were kinds of fire escapes…. The First Agricultural Bank, First National at one time, which was beautiful, it was all marble inside, that and the YMCA building were the only two that—they had to work hard on to tear down. The others came down quite easily, they—really were in need of so much TLC and hadn’t gotten it, and so they…they took them down very easily. The one story that we tell about is the Berkshire Bank which, on the front, was…massive, and when you went in the front door they took you all the way through the bank and went through the gates that they had locked to get into your safe deposit box, and when they were starting to take the building down, it was on the corner of Main and Bank Street, and on the Bank Street side it was brick, it wasn’t these beautiful big stones that were on the front. And they took out one brick, and could reach right into the vault.

Regarding her excursions to Main Street as a teenager, Linda Saharczewski commented that there was always some type of urban renewal stuff going on, so there was always some kind of an excitement. Rose Marie Thomas recalls that she had been similarly optimistic, but the lack of subsequent development slightly disillusioned her: urban renewal was good, but when you take a building down you got to know what you’re going to put in its place; they didn’t, they just took buildings down.

Looking at the north side of Main Street from the empty lot of former south Main Street and Bank Street in 1981. Initially, some residents were eager for the redevelopment local government promised. After a decade’s long wait, many grew weary, and when development finally did occur, it fell short of many residents’ expectations.

In response to whether people viewed urban renewal as progressive or negative, Judith McConnell states,

There was a big dividing group. One group thought “oh, this is wonderful. We’re going to have,” because we were, they were promised this is going to happen and that. Well, for 10 years nothing happened. And then they put a Kmart on our Main Street. Which I thought, you know, everybody they didn’t think that was a good thing either.

McConnell’s personal opinion regarding urban renewal is that it was not good, which she bases in part on its implementation: some of it [buildings] was dilapidated and probably needed to be taken down but I think one fell swoop like they did was not good. And she recalls that the victims of renewal included not only crumbling buildings, but also healthy businesses and people that lived in the vicinity: I had friends that lived on the street where the Boston Seafood, where all those things are now….They had to find other places to live. Importantly, she emphasizes urban renewal’s disrespect for the city’s rich history,

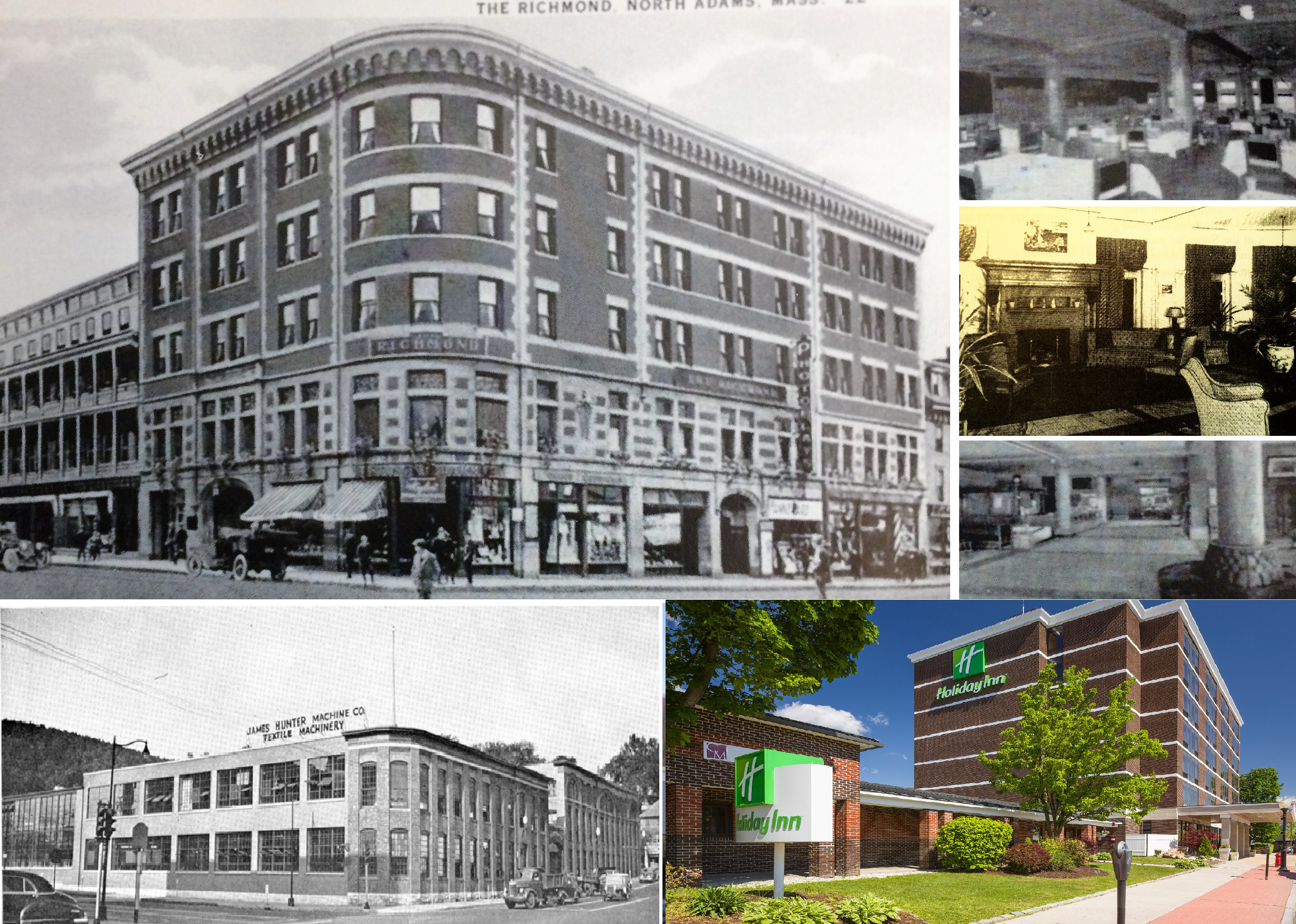

And yes, in one fell swoop our whole, I mean we had a huge hotel on the corner where the hotel is now, the Richmond Hotel was there. And on the corner where the mayor’s office is, that was Hunter Machine. So all that went. Hunter Machine did move down onto South Church Street. But these were old historic buildings. And I guess I liken it to the fact that I went to Austria one year. To Innsburg. And you see all the old buildings there. And they’re not tall skyscrapers. It’s from the old country. And I said to my sister, “they don’t tear stuff down.” I said, “look at us. Our whole history of North Adams, gone.” I don’t think that would happen in this day and age because you see they’re doing the buildings that are here, the old buildings that were manufacturing cotton, they’ve turned them into artists’ lofts and apartments, so they’re preserving. They’re not destroying. But some of it’s a little too late because the stuff that’s on Main Street you can’t replace. And all the businesses, you know. For what? Time marches on.

On the top left is the Richmond Hotel (later renamed the Phoenix Hotel, although many residents continue to refer to it as the Richmond), one of the most prominent buildings in North Adams until it was destroyed during urban renewal. To its right are pictures of its lavish interior taken at various times. A hotel has occupied that corner since the mid-19th century, when the Richmond family built atop the plot of the North Adams House, which was one of the city’s first hotels. In the right-hand corner is the present day Holiday Inn, which now occupies the plot where the Richmond sat previously (west end of Main Street on the corner of what today is American Legion Drive). Located just west of the Richmond on Main Street was James Hunter Machine company, depicted in the bottom-left picture. It was once a leading manufacturer of textile machinery that a famous local family, the Hunters, owned and operated from 1840 to 1970.