Zen appeared in almost every concept we encountered on our trips throughout Kyoto. To contextualize these experiences, we received a lecture from Professor Catherine Ludvik, who discussed Zen’s history in Japan, its presence in modern times, and Buddhist art. We learned about Bodhidharma, the famous monk who introduced Buddhism from India into China, where it eventually spread to Japan in the 6th century.

A portrait of Bodhidharma in Tenryu-ji

Japanese Zen then developed into three separate sects: Rinzai, Soto and Ōbaku. From history, we transitioned into the various types of gorgeous Japanese Zen art. Most notable were the Fusuma-e, or sliding screen paintings, traditionally natural landscapes drawn in ink. However, in modern times, some temples have allowed for new interpretations; for example, a manga artist drew this pretty, cartoony paradise.

Manga artist Kenichi Kitami’s “Rakuen”

We finally studied the innumerable temples that dot the Kyoto cityscape. Each contains the Shichidō garan, seven characteristic halls that comprise the most important buildings in each temple. Among others, there was the temple Daitokuji.

One of the constituent buildings of Daitoku-ji

There was also the amazing Tenryu-ji.

A view of the garden in Tenryu-ji

Finally, we learned about Myoshin-ji, where we ultimately stayed a night and were lucky enough to learn from Zen Priest, Daikou Matsuyama.

The grounds of Myoshin-ji

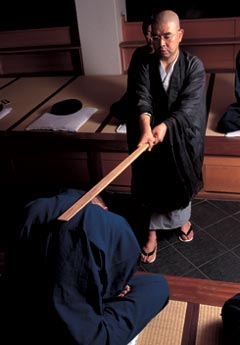

We participated in a fifteen minute meditation session, personally experiencing the Keisaku, or the cricket-bat-like stick used to wack drowsy meditators.

The Keisaku in action

We concluded with a tour of the grounds of Taizo-in, the subtemple of Myoshin-ji where Daikou works.

The white rock Zen garden in Taizo-in

Daikou brought us through the temple’s Zen garden and told us about one of the most famous koans (Zen riddles used to provoke enlightenment)—how to catch a large catfish with a small drinking gourd, as depicted in this famous painting.

Josetsu’s “Catching a Catfish with a Gourd”

As an answer to this Koan, Daikou’s grandfather had designed a gourd-shaped pond and placed two catfish inside of it.

Daikou looks out at the pond

His answer perfectly encapsulates the wisdom of Zen—actions matter much more than words, or thinking for that matter.

These experiences illuminated the extraordinary will power of Zen practitioners. We saw how Zen Buddhists participate in some form of cleaning every day, resulting in spotless temples. The work ethic required to become a monk—to endure three years of training on three hours of sleep per night—humbled me, while the beautiful structures dedicated to Zen concretized the idea that many people have dedicated their lives to this cause, and want to share that with the world.