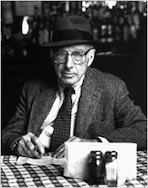

MITCHELL, JOSEPH (1908-1996). Joseph Mitchell grew up in Fairmont, North Carolina, a farming town in the state’s coastal plains. In 1929 Mitchell moved to New York City and began his career working as a crime reporter and feature writer for The World, The Herald Tribune, and The World Telegram. In 1931 he signed on as a deck boy for the Hog Island freighter The City of Fairbury, bringing pulp logs to New York City from Leningrad. After his return Mitchell continued to work as a journalist until 1938, when Harold Ross hired him to write for The New Yorker. Mitchell stayed at The New Yorker until his death in 1996, though “Joe Gould’s Secret” (1964) was his last published piece . Mitchell’s case of writer’s block is one of the more famous and puzzling ones. He continued to come in to his office at The New Yorker, and his daughter remembers that “He had oceans of paper in many file cabinets, at home and at the office,” yet Mitchell never published again. In his eighties, Mitchell admitted that “The hideous state the world is in just defeats the kind of writing I used to do.” During these years he spent more time in South Carolina and became involved in reforestation projects. Mitchell also maintained membership in several societies dedicated to preserving history and the arts, including serving from 1972 to 1980 as a founding board and Restoration Committee member of the South Street Seaport Museum.

My Ears Are Bent (1938) is a collection of Mitchell’s early newspaper features. While reporting brought him in contact with celebrities like Albert Einstein, Bing Crosby, and George Bernard Shaw, the inhabitants of the forgotten corners of Harlem, The Bowery, Greenwich Village, and New York Harbor that Mitchell encountered working the night shift interested him more. Several pieces in My Ears Are Bent foreshadow later New Yorker profiles. Echoes of “Saltwater Farmers” can be found in “Dragger Captain” and “The Rivermen,” both of which appear in the collection The Bottom of the Harbor (1960).

Mitchell published four collections of stories originally printed in The New Yorker: McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon (1943), Old Mr. Flood (1948), The Bottom of the Harbor, and Joe Gould’s Secret (1965). Up in the Old Hotel (1992) is an omnibus collection of the four earlier volumes, with some additional stories included. McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon chronicles New York’s drunks, gypsies, street preachers, and steel workers, among others. Like Mark Twain, Mitchell employs dark humor and blurs the line between fiction and nonfiction. David Remnick, a later editor of The New Yorker, described McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon in his 2008 introduction to Up In the Old Hotel as the Dubliners of New York City. Mitchell included one waterfront story, “A Mess of Clams,” in McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon. Old Mr. Flood, which Mitchell described in the author’s note as a series of “truthful rather than factual” stories, is Mitchell’s first focused examination of life on the waterfront. He created the Mr. Flood character from a composite of several real men involved in the Fulton Fish Market.

Mitchell wrote the stories in The Bottom of the Harbor, his influential collection of sea stories, between 1944 and 1959 with the nostalgic understanding that these people and places with traditional maritime skills and sensibilities would soon disappear. Like John Steinbeck’s examination of the Monterey waterfront community in Cannery Row (1945), Mitchell uses individual characters to reflect on cultural changes. The result is a record of the New York waterfront’s decline in economic and cultural prominence. Like much of Mitchell’s work, the pieces in Bottom of the Harbor are also stories about storytelling. In particular, “Dragger Captain” is a masterful portrait of Captain Ellery Thompson of Stonington, Connecticut, as well as a carefully crafted meta-story. The success of “Dragger Captain” led to Thompson’s publishing two books of his own entitled Draggerman’s Haul: The Personal Story of a Connecticut Fishing Captain (1950) and Come Aboard the Draggers: Sea Sketches (1958). Mitchell’s interest in architecture drives “Up in the Old Hotel”, a quasi-ghost story about Louis Morino, proprietor of Sloppy Louie’s, and the building Morino owns. “The Bottom of the Harbor” begins with a topographical tour of New York Harbor’s filthy but teeming waters before Mitchell turns to a natural history of the marine life and fishermen tied to it. Roy, a “harbor nut,” delivers the line: “I don’t even worry about the pollution any more. My only hope, I hope they don’t pollute the harbor with something a million times worse than pollution.” Mitchell also presents the ways in which the sea influences communities, tracing the history of the rats that infest New York’s streets in “The Rats on the Waterfront” and examining the spiritual attachment the sea creates between a true riverman and the water in “The Rivermen.” While Mitchell has an affinity for the waterfront, it also seems to overwhelm him with all-too-clear signs that this maritime culture is slipping away. In “Mr. Hunter’s Grave,” Mitchell escapes to the waterfront’s roots and Mr. Hunter’s stories. He opens with the line, “When things get too much for me, I put a wild-flower book and a couple of sandwiches in my pockets and go down to the South Shore of Staten Island and wander around awhile in one of the old cemeteries down there.”

In Mitchell’s final publication, the lengthy profile of Joe Gould titled “Joe Gould’s Secret,” Mitchell develops the understated qualities in his previous stories. While not a particularly maritime story, “Joe Gould’s Secret” is perhaps the best representation of both Mitchell’s craft as a writer and his perceptive and respectful treatment of his subjects.

Even before his arrival at The New Yorker, Mitchell was such a popular reporter that his picture appeared on newspaper delivery trucks. The New Yorker heralded Mitchell as a standard-setter during his tenure there, and he is still admired for his exceptional talents as a listener and observer. His subjects’ words make up long sections of each piece, and Mitchell paces their vignettes with a natural storyteller’s attention to timing and detail. The pieces can be read as metafictional considerations of transience and change, yet are also filled with what Mitchell described as graveyard humor. Mitchell deftly guides his reader’s curiosity through his own to create poignant and sharp explorations of daily life in New York City and the waterfront.

My Ears Are Bent (1938)

Archive.org

Google Book Search

The Bottom of the Harbor (1960)

Archive.org

Google Book Search

Old Mr. Flood (1948)

McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon (1943)

Further Studies:

Adams, Tim. “Joseph Mitchell: mysterious chronicler of the margins of New York.” The Guardian. 30 June 2012.

“Joe Gould’s Secret (2000).” IMDb.com, Inc., https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0172632/.

“Special Issue No. 26: Joseph Mitchell.” Pembroke Magazine, 1994.

Rundus, Raymond J. “Joseph Mitchell Reconsidered.” The Sewanee Review. Vol. 113, No. 1, 2005, pp. 62-83.

Severo, Richard. “Joseph Mitchell, Chronicler of the Unsung and Unconventional, Dies at 87.” The New York Times. 25 May 1996.

Singer, Mark. “Joe Mitchell’s Secret.” The New Yorker. 22 Feb. 1999.

keywords: white, male