As my parents shared the news with me about how there was a new virus moving quickly through the streets of Wuhan, I stared at the screen, my eyes on the video call, but my mind elsewhere. A week later, when we called again, they began telling me about their friends who had contracted the virus. I listened and nodded. It was mid-January; I was caught up in the excitement of Winter Study, and the existence or effects of a coronavirus halfway across the world did not seem very real to me.

After President Mandel announced the closure of the College on March 11, I ran down the stairs of Schapiro and burst outside to the lawn, where others were frantically on their phones. When I called my parents to tell them the news, my dad was unfazed by my expression of shock and uncertainty at the decision. My mom had already fallen asleep, and he did not bother to wake her up and let her know. To a couple who had been living in the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic—who were evacuated on a cargo airplane back to the States and quarantined in a military base for two weeks—to a couple who had experienced so many transitions in the past several weeks that they were now living from Airbnb to Airbnb, the unexpected news of the College’s shutdown was not so unexpected for them.

My parents moved to Wuhan in the winter of 2018, but because I was attending an international boarding school in South Korea, I never lived in Wuhan for an extended period of time. Even so, I have a connection to the city. I have run through its streets, meandered along paths following its many lakes, conversed with its residents and visited museums to learn its history. Yet how separated was I from my parents that I was unable to empathize with their grieving and their mourning for the city that they were living in.

In the Purple Bubble, I often find myself forgetting the reality of death and suffering in this world (whether from COVID-19 or not), focused instead on my own concerns and desires. I’m more concerned with how I’m doing in my classes, with completing my papers, with running from meeting to meeting, with being busy, busy, too busy to think about what’s happening in the world. Over the past couple of weeks, however, I have learned to re-center attention away from myself and lament.

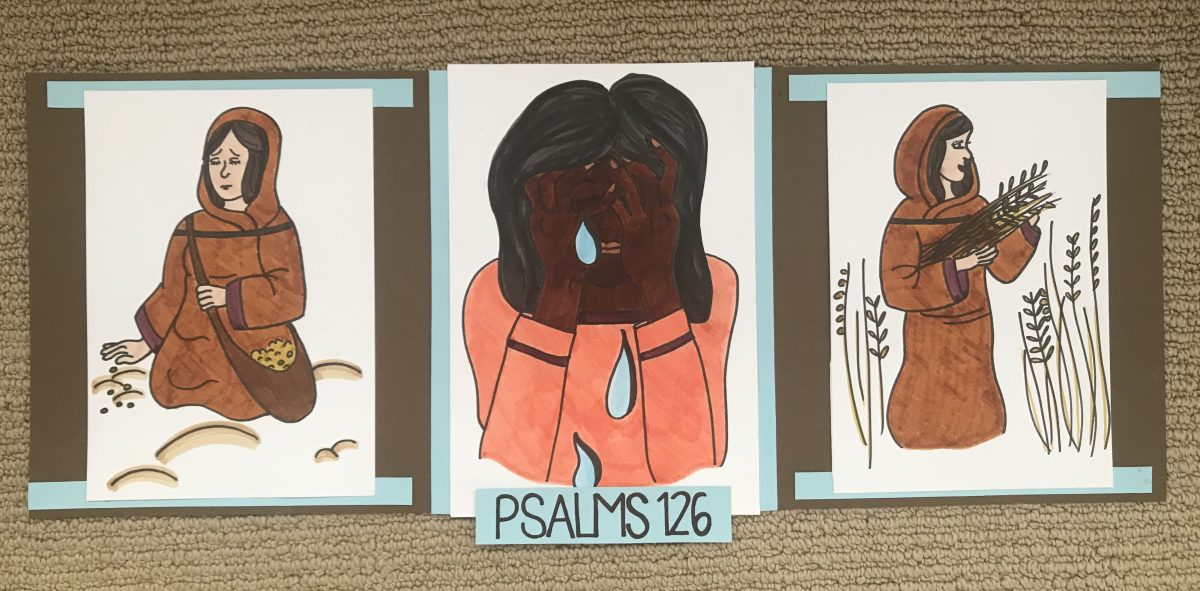

Lament is the language of suffering, the expression of sorrow and grief. It is a response that confronts the reality of people who face suffering and injustices of all kinds every day. Lament reminds us that death is not new. All lives on this earth will come to an end and forgetting is an indicator of privilege.

As a Christian, I am called to love the world as God loves the world— fiercely, intimately, sacrificially. This means that I cannot remain indifferent to people experiencing hardship across the globe. I cannot be impartial in conversations about how actions by the College can and will disadvantage certain student populations. I cannot disregard the widespread racism faced by Asians and Asian-Americans during this time, nor separate its existence from structural issues of discrimination in the United States. I cannot pretend that everything is fine or succumb to the lie that there is nothing that I can do. Doing so fails to love the way that I am called to love.

COVID-19 has exposed my apathy and laid bare my privilege. I have been able to address this privilege through lament because I can mourn for and with others. Lament is an inherently unifying act that urges me to remember how there exists a world beyond the purple bubble. I commune with those around the globe in grief; I empathize with others’ hurts as if they were my own. I lament in a way that reflects the deep love of God.

However, it is not enough to remain in a state of lament about the pandemic’s impact. Lament demands a response. If I truly love and empathize with those around me who are suffering, that love will drive me to respond with generosity. Being generous can mean using my increased time and energy to check in on my friends and family, and care for their well-being. It can mean being intentional with how I spend my money, supporting those who are struggling financially and not using my untouched spring break savings to buy more things for myself. In the midst of the pandemic, in the midst of isolation, I choose to acknowledge my privilege of ignorance and respond generously. I choose to love.

Originally posted in The Williams Record, April 14, 2020.

Written by Rebecca Park ’22