If you’ve ever watched the Hunchback of Notre Dame, you’re probably familiar with the concept of sanctuary. If you haven’t, allow me to set the scene for you. Near the end of the movie, we find Quasimodo, the titular character, chained atop the Cathedral of Notre Dame. He is crying out for Esmeralda, his gypsy “friend,” who is literally being burned at the stake in the city center. In a momentous display of strength, Quasimodo breaks free of his chains, swoops down, scoops Esmeralda into his arms, and climbs back up to the top. He holds her scorched—but otherwise alive—body above his head and shouts, “Sanctuary! Sanctuary! Sanctuary!” The crowd below riots, but they are powerless. His declaration of sanctuary protects Esmeralda and rescues her from certain death at the hands of the state.

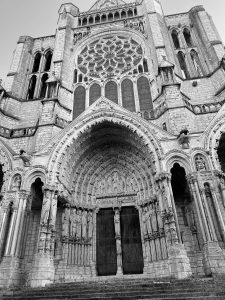

Sanctuary—in all its cinematic, political, ecclesiastical, and biblical forms—is a universal human desire. It signifies a place of refuge, a protected space that lies in the gap between life and death, flourishing and decay. To the church, and those familiar with church, sanctuary is where people are gathered and therefore, according to the Scriptures, God is with them. To the political refugee, sanctuary is a haven where they are offered life temporarily as a reprieve from the clutches of the state. To the student, sanctuary is where life is breathed back into tired eyes and buzzing brains. Yet, whether you are a migrant facing persecution from the state or an overwhelmed student, sanctuary offers something we all want: rest for our weary souls.

Growing up in a small Chinese Baptist church, I thought sanctuary was mostly a place where church stuff happened. Sanctuaries were where I did Bible Drills, played hide and seek with my friends in the choir loft, played piano while the adults were in meetings, and snuck behind the altar to eat communion wafers (whoops). Sanctuaries didn’t receive much reverence from me, much less any feeling that I would desperately want to be in one. But now, amidst surmounting political unrest, a continuing mental health epidemic, and countless other ways in which this current moment presses and crushes our souls, there has not been a day that I have not wanted and sought out sanctuary. So, how and where do we find it?

In the Bible, sanctuary is first invoked when Moses encounters the burning bush in Exodus 3. As the story goes, Moses is tending to his sheep and sees a bush on fire yet miraculously not burned up. As he approaches the bush to examine it, God calls out, “Do not come near; take off your sandals, for the place you are standing is holy ground” [1]. In the first sanctuary, God’s presence is both too set-apart for Moses to approach and too intimate for Moses to have his sandals on. There, upon that sacred ground (sancta terra in Latin), Moses receives his commission to lead God’s deliverance of the Israelites. God proclaims that He has seen the affliction of His people, and in response, He is sending Moses to free them from their slavery.

In the first sanctuary, Moses finds his purpose.

This is no mistake, nor is Moses’ response to his great commission. Moses hides his face and says to God, “Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh and bring the children of Israel out of Egypt?” At this point in the story, Moses is a mere shepherd, has a speaking problem, and is wanted for murder back in Egypt. He is, in the most human response, afraid of his calling. Moses thinks he is not enough—not well-spoken enough, not powerful enough to save the Israelites. After all, he is being told by a God-sent burning bush to go start an insurrection against the most powerful nation on the face of the earth. Of course he feels unworthy. God knows that.

God already knows who Moses is—his faults and his story—and has chosen him regardless.

Yet God’s response to Moses’ fear is not one of affirmation. It is not “you’ve got this,” or “you’ll figure it out, dude!” Instead, God says what might be the most central promise in the entire Bible: “I will be with you.” The promise shows that what is necessary is not Moses’ abilities but God’s. It shows that Moses has been chosen, but God is the one who is crucial. This is God’s promise to expand that first sanctuary—extending, through Moses’ faithful movement, the places where God is with man. God’s plan for the Israelites is to extend His presence and power beyond the burning bush, using His chosen shepherd to lead His people to freedom.

And yes, this all points to Jesus. It always does.

When Jesus came, fully God and fully man, He extended that sanctuary to the ends of the earth, to every people, tribe, and tongue. Jesus, God-with-us, is the perfect embodiment of what it means for God to dwell with man. Just like Moses, He offers freedom to all that follow Him into it, and just like God, He invites us to join Him in that same mission.

—

I suggest to you, dear reader, that the way we create and become sanctuary for others is the ultimate way we reflect God’s love. I believe that if we truly grasped and embodied what it means to be a sanctuary for the world, to be a saving space filled with hope, we would become more like Christ. And in that becoming, we would display to the world the power, magnitude, and temerity of God’s love. Nothing is greater than that call.

And so, as you seek sanctuary for yourself or others and ask where sanctuary can be found, I ask you Moses’ question: Who are you? Who are you becoming?

I only ask, and care, because a sanctuary requires people. Inside sanctuaries, God helps us do the holy work of connecting places to their purpose and people to their Creator. It is where God, through His people and His power, does the unexplainable, sets the oppressed free, and brings life to the lifeless. A sanctuary is where God meets man. It is the kingdom of God made manifest. And as Moses’ story shows, that requires people.

A sanctuary does not have to be the Exodus or some cinematic heroic moment. It does not require stained glass windows or marble columns. Not all expressions of sanctuary must be momentous. Sometimes sanctuary looks like an elderly undocumented woman living at the church because otherwise she’d be deported. Sometimes it looks like taking a deep breath and saying, “Jesus, come.” Sometimes it looks like the carpeted room in the back of the basement where you can escape from the worries of the world and have friends pray over you. Sometimes it looks like a hug.

So I ask again: Who are you? Who are you becoming? In what ways are you becoming a sanctuary? Do you believe God wants to be with you in every moment? How are you extending the miracle of presence to the hurting? Have you been a safe space for the weary? Are you taking part in God’s mission to set people free? If you’re afraid of that calling or stuck in that becoming, welcome to the party. I’m glad you’re here. You’re not alone. God is with us.

FOOTNOTE

1: Exodus 3:5, New American Standard Bible.

Loren Tsang ’22 majored in Political Science with a concentration in International Relations and Leadership Studies. He now works at Buckhead Church in Atlanta in their college ministry while pursuing a Masters in Christian Leadership at Dallas Theological Seminary. In his free time, he enjoys going to the gym, making music, chasing sunsets, and cooking with his mom.