The area around the river Dijver, the oldest part of Bruges, has been settled since the first century. The foundations of the modern city, however, date from the 9th century, when the first known Count of Flanders established his residence by the river Reie. Beside his castle, he dedicated the church of St. DonatianThe history of the Sint-Donaaskerk is as old as the city of Bruges itself. In the mid-9th century, when the first known Count of Flanders set out to build a fortress on what is now Castle Square in modern Bruges, he came across the ruins of a 4th century settlement – including a church dedicated to St. Mary…, Today’s “burg” square, at the heart of the modern city, was the site of the Count’s castle.

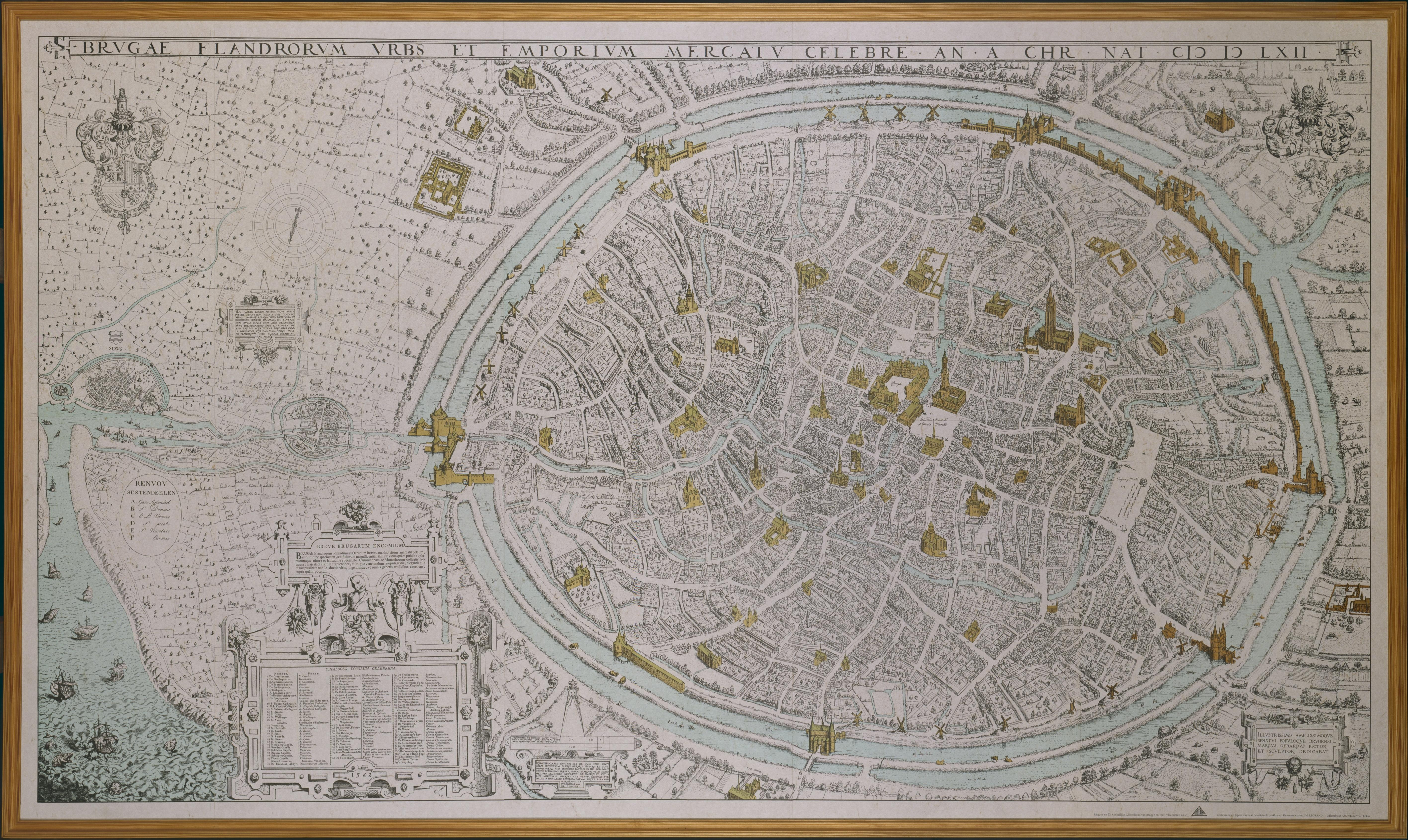

By Obrecht’s time, the layout of Bruges roughly resembled the modern city, characterized by a system of canals called reien – but its earlier geography is not well known. Some of its waterways are thought to be natural, but others were certainly manmade in an effort to aid transportation and trade. The Zwin channel, which connected Bruges with the North Sea, was the most important manmade channel, and made possible the success of Bruges as a trading center. Some of the reien can be seen in the 1562 map of BrugesMarcus Gheeraerts the Elder (ca. 1520 – ca. 1590) was born in Bruges, but may have had early training and employment in another town before joining the Guild of St. Luke in 1558… by Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder:

From the 13th century onward, Bruges was one of the most developed and prosperous cities in Europe. Like many cities in the area, it began as a center of textile manufacturing, and by the 15th century had expanded to produce and export a wide range of luxury goods – especially fashion, art, and fine crafts. But Bruges’s most profitable sector was its highly advanced banking system. Moneychangers and bankers were among the most important figures in the city, offering loans, investments, and money transfers, and collaborating with hoteliers to service foreign businessmen visiting the city. International visitors were common in Bruges, and they brought with them the latest products, trends, and ideas from across Europe.

These factors contributed to the strength of Bruges’s middle class. Most nearby cities were purely industrial, with a clear divide between the elite, entrepreneur class and the peasant workers they employed. But in Bruges, the diversity of people, trades, and activities gave traditionally lower-class workers the chance to become entrepreneurs in their own right. Bankers, money-exchangers, merchants, craftsmen, and clergy were all part of this thriving social group.

This wealthy middle class was largely responsible for the impressive production of art and music in late medieval Bruges. Celebrated painters, including Jan van Eyck, Petrus Christus, and Hans Memling all worked in Bruges in the 15th century. Although they were often employed in the court, artists found additional work in commissions by private citizens. It is no coincidence that some of the most famous pieces from this period are painted panels and altarpieces – they were either commissioned by churches themselves or by wealthy citizens who donated them to the churches to which they belonged. The Lamentation TriptychThe Lamentation triptych (ca. 1475), linked to the Master of the St. Lucy Legend by the pomegranate pattern worn by St. Donatian, bears a connection to Obrecht’s Mass for Saint Donatian in both its original location and its donors… commissioned by Donaes de MoorDonaes de Moor belonged to the upper eschelon of the merchant class in Bruges… and Adriane de VosAdriane was one of five children of Jacob de Vos and Isabel van der Stichelen to reach adulthood… is a good example of such a donation. Another example is the altarpiece Virgin and Child with Canon Joris van der Paele, Saint Donatian, and Saint John by Jan van Eyck , which was commissioned in 1434 by a local canon, Joris van der Paele, for the altar of his own tomb at Sint-Donaaskerk.

, which was commissioned in 1434 by a local canon, Joris van der Paele, for the altar of his own tomb at Sint-Donaaskerk.

Musicians also flourished in 15th century Bruges. Like Obrecht, many musicians were employed by churches, but they augmented their work by composing and performing music requested by individual patrons. Beyond the “art music”, which was generally reserved for performances in church, popular music filled the streets. City minstrels, playing trumpets and other wind instruments, signaled civic events – the arrival of important guests, significant meetings, tournaments, and executions. On feast days, music was at the heart of local celebrations. Records exist documenting as many as twenty festival processions in Bruges in a single year, with instructions for special songs to be performed at specific locations throughout the city.

Despite its continued economic and cultural success, the 15th century was also a period of political crisis in Bruges – and the beginning of its decline. At this time, Bruges was the capital of the Burgundian Netherlands, a collection of semi-independent fiefdoms under the authority of the French king. This put the city in the crossfire of ongoing conflicts between France and England, which limited its opportunities for international trade and occasionally led to direct attacks. In addition, two rebellions against the Burgundian Duke Philip the Good ravaged the city. As a result, it struggled with famine, economic depression, and plague in the middle of the 15th century. The final blow came in 1482, just years before Obrecht moved in Bruges, when the Duchess Mary of Burgundy died; the city’s revolt against the rule of her widower, the Archduke Maximilian of Austria, was violently suppressed, and it never fully recovered. While exploration offered new opportunities for prosperity in the 16th century, Bruges would never again be such an important, international hub. Obrecht’s time there was thus poised at both the peak of its economic and artistic prosperity, and at the beginning of its decline.

Anna DeLoi with M. Jennifer Bloxam

To learn more about Bruges in 1487, see:

Geirnaert, Noël, and Ludo Vandamme. Bruges: Two Thousands Years of History. Bruges: Stichting Kunstboek, 1996. See in particular pp. 7-11, 25-37, 43-53

Strohm, Reinhard. Music in Late Medieval Bruges. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985. See in particular pp. 1-10