Tyler Durden says, “We’re the middle children of history, man. No purpose or place. We have no Great War. No Great Depression. Our Great War’s a spiritual war… our Great Depression is our lives. We’ve all been raised on television to believe that one day we’d all be millionaires, and movie gods, and rock stars.” Fight Club is a coming-of-age movie for the men of Generation X. The movie explores a male-centric critique of American cultural collapse epitomized by emasculation, domestication and materialization and gives extreme solutions to these crises. Fight Club forces its predominantly male audience to reconsider their whole lives. We question whether our lives mean anything, whether our work brings happiness and satisfaction, and whether we are overwhelmed by cultural censorship and mundanity. The desire to escape these problems motivates every decision the main character(s) make. Tyler Durden, the Narrator’s alternate personality, continually pushes the Narrator’s conscious personality (and the audience) to examine the oppressive culture of capitalism. We analyze the Western way of life from an anarchical perspective. This movie portrays Western culture mired in the mundane repetition of industrial production. Social mores mold us as pawns of capitalism: following authority, emulating models, buying useless shit, and censuring ‒ through the use of force or the suggestion of force ‒ contradictory advice. We must ask ourselves if we are comfortable with the repressive forces that act to domesticate us and if our lives improve through the acknowledgement of these forces.

Emasculation

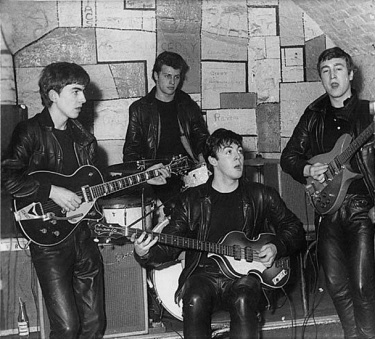

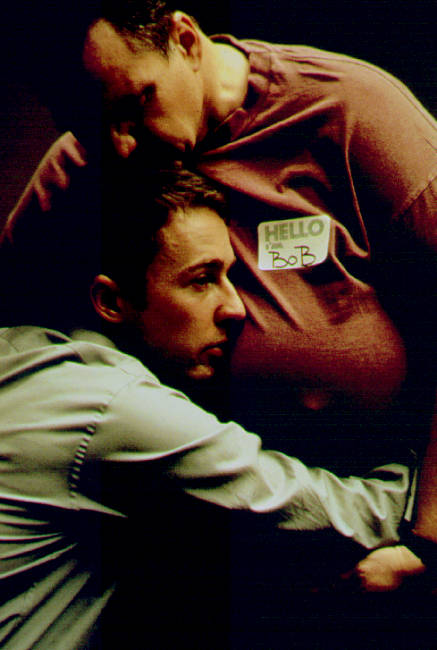

Fight Club pummels its audience with the loss of manhood and masculinity in modern society. This theme is present throughout the movie. Tyler claims that “we’re a generation of men raised by women.” This statement summarizes the American era of maternal child-care with working fathers. This apparent problem is dramatized when the Narrator struggles with insomnia at the beginning of the movie. He copes with the crippling lack of sleep that zombifies his personal and professional life by attending support groups. He finds comfort in listening to other’s painful stories, receiving sympathy, and crying into Bob’s “bitch-tits”.

These sessions make Bob the equivalent of a surrogate mother. The movie suggests men today rely on the warm, pitying support of mother figures to relieve the anxiety of repetitive lives.

Tyler catalyzes the shift in the Narrator’s life. The Narrator admires this gruff, manly figure ‒ a new mentor offering a different path to comfort.

Tyler introduces himself to the Narrator on a plane in the first thirty minutes of the movie, and they stick together until the conclusion. The movie reveals that Tyler is actually a figment of the Narrator’s imagination, an alternate personality that exists to change the Narrator’s life and make him stronger. Introductions aside, after they meet on the plane, the Narrator goes home to find that Tyler/he blew up his apartment. He calls Tyler for help and a place to stay. Tyler forces the Narrator to verbally ask for help. This is the first step towards a new, masculine life for the Narrator. The Narrator has to take control of his actions and, man-to-man, ask for help. The scene ends with Tyler proclaiming, “It could be worse. A woman could cut off your penis while you’re sleeping.” This shocking alternative emphasizes the central focus on masculinity.

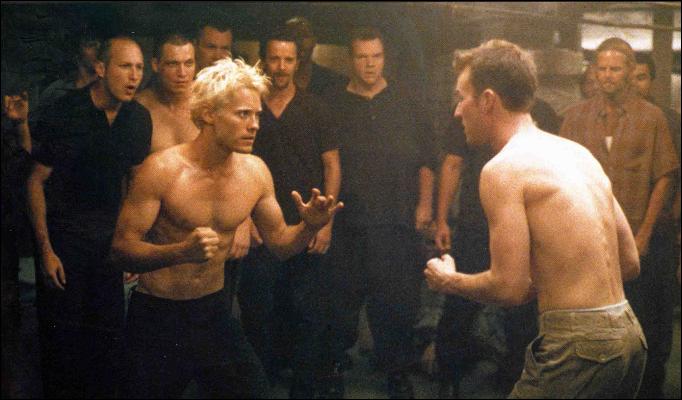

Tyler and the Narrator’s relationship truly begins when they form an ultra-masculine “fight club”. Tyler fights instead of crying and seeking comfort in support groups. This strictly male club meets in a basement periodically to fight. The fights are not about winning or losing but rather about building strength and confidence and fulfilling a primal urge.

The Narrator and Tyler begin “sizing” everybody up ‒ even historical figures such as Lincoln. Fight Club presents fighting as the solution to the emasculated male population of America. The previously weak Narrator now stands up to his boss at work. He flaunts injuries. He is no longer afraid, anxious, or disgusted with himself. The Narrator, in his Tyler persona, continues to spread the cult of fighting across the country in new cells. He also assigns “homework” to members. They are supposed to pick a fight with a complete stranger and lose. This reaffirms the movie’s message that fighting isn’t about winning. Fighting taps into a primal pleasure, a fighter’s pain and adrenaline create a unique internal calm. The calm satisfaction that results from fighting is the salvation for the feminized male population.

Domestication

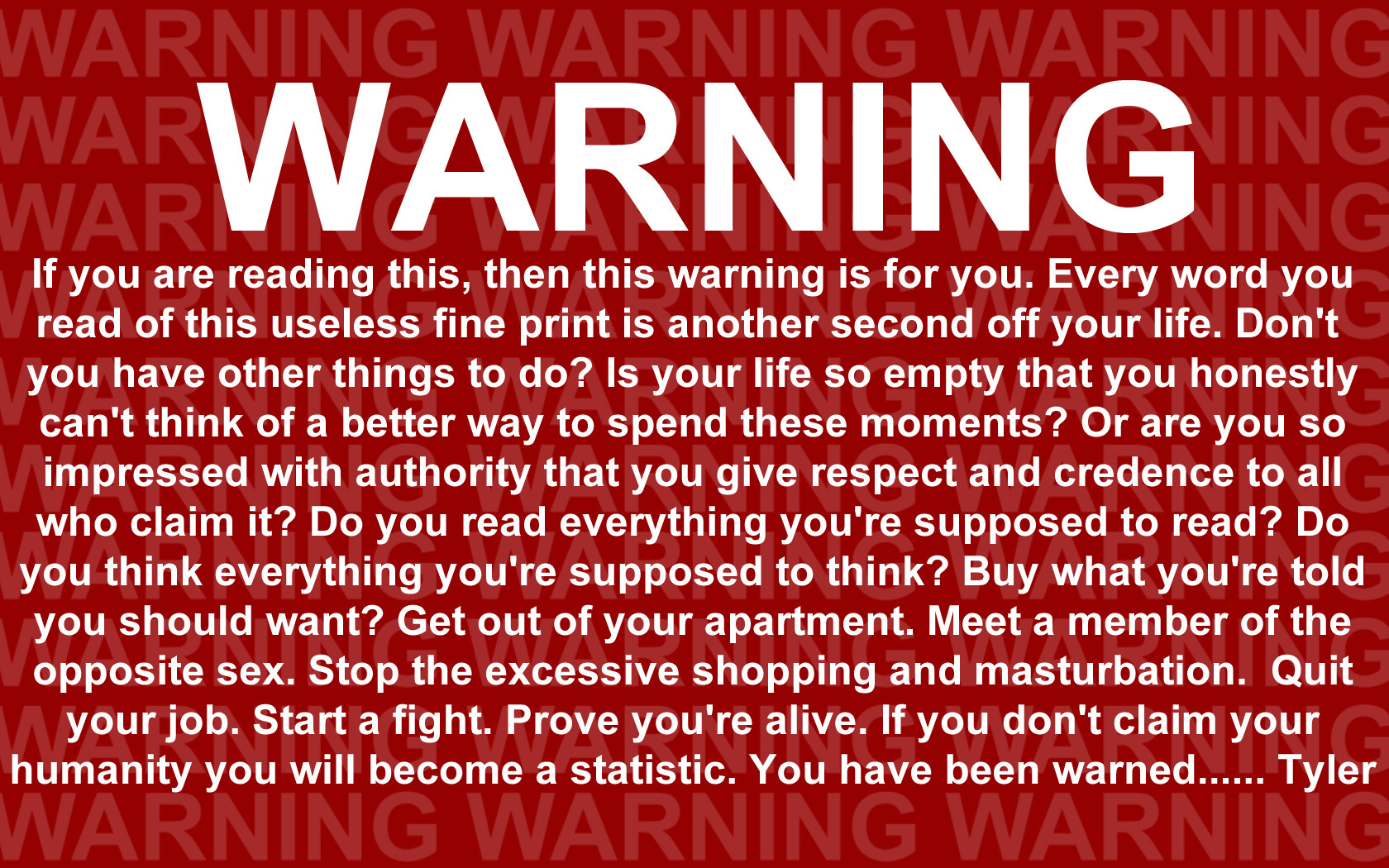

Fight Club frequently suggests that the domestication of individuals in society prohibits meaningful existence. The movie uniquely oscillates between domestic or anti-domestic culture. Before the DVD menu opens and after the FBI message forbidding piracy, a message from Tyler hides in plain sight.

This movie mocks the people who take the time to read government warnings. If you read this message, you’re a drone, a sheep. Tyler’s message harrangues readers about the absurdity of following government advice and the societal pressure to overconsume. Through ridicule, he calls for men to rise up, be spontaneous and “prove” that they are alive and conscious in this world. The opening scene solidifies this theme. We meet the Narrator, who travels frequently for a job that he hates, describing his life in terms of repetitive, forgettable, disposable units: airplane meals, individually packaged soaps, and “single-serving” friends. His life is an anonymous cycle without trouble, excitement, or spontaneity. He prays for a plane crash to end the repetition. He dreads returning to his “filing cabinet” apartment.

Tyler ends this domestic life in an instant by blowing up the Narrator’s house, a move that forces the Narrator to live with Tyler in a run-down, wild house far from civilization.

Tyler works as a projectionist in a theater where he splices glimpses of porn into family movies and as a cook in a fancy restaurant kitchen where he urinates in the soup. He sells soap he makes using human fat stolen from a liposuction clinic. Through these jobs and actions, Tyler shatters the shelter of our privileged lives and our disconnection from the real world. Over the course of the movie, Tyler helps free the Narrator from his numbing nine-to-five job. Tyler’s jobs are some of the movie’s solutions to the problems that arise when a society becomes domesticated. He wants us to be more primal, more focused on survival, more alive.

Materialism

Fight Club also draws attention to society’s infatuation and obsession with materialism. Hatred of consumerism drives the plot. When the Narrator describes his home, he states, “Like so many others, I had become a slave to the IKEA nesting instinct.” He obsessively buys useless shit for the sake of buying. He buys food that he doesn’t eat. He buys designer clothes, a form of “masturbation”. He watches the Shopping Network for entertainment. Tyler breaks this dismal cycle with nitroglycerine, blowing it all onto the street. Tyler instructs us to destroy the consumerist culture that plagues the world of Fight Club, but we must personally determine if we find this culture a issue in modern society.

Fight Club also insists popular culture is obsessed with masturbation. Fight Club’s term “masturbation”, emphasizing the self-pleasure connotation, means any form of self-improvement to meet society’s standards. Giving up masturbation means no dieting or working out to look like models, no liposuction to become skinny (when the real problem is poor nutrition in the modern diet), and no shopping for brand-names. The film rails against narcissistic investments to improve our looks in unnatural ways. We should not derive pleasure from wearing Ralph Lauren or by going to the gym to look like Brad Pitt (Tyler).

Tyler sums up the incessant materialism of society in three ways: 1.) “Advertising has us chasing cars and clothes, working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don’t need”; 2.) “The things you own end up owning you”; and 3.) “You’re not your job. You’re not how much money you have in the bank. You’re not the car you drive. You’re not the contents of your wallet. You’re not your fucking khakis. You’re the all-singing, all-dancing crap of the world.” The capitalist nature of modern society infuriates Tyler, who, in turn, asks us to embody his anger. Corporations bombard us with advertisements 24/7. People salivate for material wealth while compromising their happiness in jobs they hate. Tyler implores the audience to understand that we are not what we own or possess. Living a fulfilling life trumps everything.

Tyler states that “it’s only after we’ve lost everything that we’re free to do anything.” This is where Project Mayhem comes in ‒ the climax of the plot and Tyler’s ultimate goal. Behind the Narrator’s back (actually while the Narrator persona is sleeping), Tyler organizes multiple cells of trained fight clubbers to carry out anti-corporation attacks. They detonate explosives on the foundations of a corporate work of art which then rolls into, and destroys, a corporate coffee shop. They vandalize large corporate buildings. They destroy Apple computers in a store. They accomplish their end goal, blowing up credit company headquarters which erases the debt record. They aim to stymie consumerism and devastate a corporate industry that survives on our materialistic addition. Fight Club’s answer to materialism is the destruction of capitalism.

Fight Club uses visual and auditory elements that imitate advertising tactics. David Fincher, the director, hides a Starbucks cup in every scene. The Narrator claims that in the dystopian future, “when deep space exploration ramps up, it’ll be the corporations that name everything, the IBM Stellar Sphere, the Microsoft Galaxy, Planet Starbucks.” This movie asks us to relook at these seemingly convenient corporations as tyrants seeking to control our lives. Subconscious mind-control through advertising is this story’s antagonist. Even the song that concludes this film, “Where is my Mind” by the Pixies, instructs us to reconsider our existence in society and break-free of our capitalist chains.

What does this all mean?

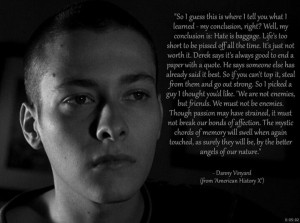

Fight Club forces its audience to scrutinize the cultural ideologies of the society in which we live. The gender ideology of masculinity this movie adopts almost exclusively portrays male characters. Fight Club has only one significant female role. Her primary purpose is to tease out the strange relationship between Tyler and the Narrator and dramatic concluding reveal that they are the same mind. The supersaturation of male roles emphasizes the varying levels of masculinity of each individual. This automatically forces the audience to examine their own views of masculinity in today’s culture, challenging us to find compelling evidence against Fight Club’s theory of emasculation. The same challenge is presented in the ideologies of anti-materialism and anti-domestication. These core ideologies provide a broader critique of capitalism ‒ a critique reflected in the current rebellion against political and corporate interests, driven in large part by disenfranchised white men.