Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games is one of the most widely read dystopian novels in recent years, and its film adaptation was one of the most successful movies of 2012. Its concept: out of the ruins of North America rose Panem, a country separated into thirteen districts and an oppressive Capitol. The districts eventually revolted, and the Capitol lashed back, in the process destroying District 13 and doubling down on their oppression. The Treaty of Treason decreed that every year after the rebellion, each of the twelve remaining districts send one boy and one girl, known as tributes, to fight to the death on national TV. It’s the most hyped-up show of the year: the Hunger Games.

One could contend that Collins writes to caution us all, as civilization might well be heading toward such chaos. Another could stake a more present-day argument, that the Hunger Games is a dark satire against ruthless capitalism. But teenagers flocked to the theaters to experience The Hunger Games—do young people really want so badly to watch a movie about politics, or economy? Maybe, but there’s an explanation even closer to home.

Before I get there, though, I have to bring in a philosophy of ideology presented by Louis Althusser. Ideology runs far deeper than a set of values, a worldview, or a bias. Ideologies are ubiquitous and can operate subconsciously, feeding us ideas. Stories hold particularly strong ideologies; in order to enjoy a story, we have to buy whatever it is selling. To that end, effective stories tend to do two things. First, they present some real social crisis, and then provide a fantasy answer. They offer fictional solutions to real problems. This process doesn’t work unless the problems and solutions resonate with the audience—in the case of The Hunger Games, all of us. So if teens are flocking to the theaters, adults of all ages close behind, the real, everyday social crisis illuminated in the Hunger Games has to be one that resonates with most everyone. Which it is: it’s a crisis straight out of high school.

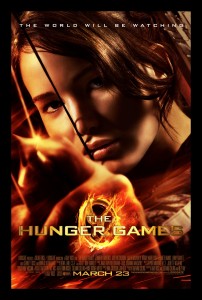

The story focuses on Katniss Everdeen, a sixteen-year-old tribute from District 12. All the participants are between twelve and eighteen (fine, middle school should be included, but most of the tributes are in their mid to late teens). At their most basic level, the Games are like high school because they ‘aren’t real.’ In school everyone seems to talk about the real world, whatever that means, and the fact that school is not the real world. Navigating the ever changing, brutal, and cutthroat teenage social scene is indeed often a game. The Hunger Games are the same, except instead of gossip, a roaring forest fire shooting cannonballs of flame could sneak up on you at any minute. Rule changes are expected, and the stakes are life and death.

But, you say, life and death seems quite intense for high school, an extreme exaggeration. Really? Over fourteen percent of high school students have considered suicide, and almost seven percent have attempted it. That’s not counting the many more who suffer from depression or other mental health issues due to social interactions—high school is quite the serious game. Life-and-death stakes work for this over-glorified version of high school because while it seems like a game, a show, on the surface, the most raw and real of emotions are right behind the façade. Teens and children experience primal fear as residents of the Capitol watch with amusement, judging them (literally—they’re objectified before the Games on a scale of 1-12) and betting on who will win.

Status and appearance are everything. The first piece of advice that Haymitch Abernathy, former Games winner and District 12 mentor, gives Katniss and Peeta is, “Wanna know how to stay alive? You get people to like you.” He wasn’t directly talking about high school, though he might as well have been. High school is a whole different game if you don’t have friends. The tributes’ first impression in the Capitol before the games is in a parade, of which the importance “cannot be overstated.” Like at the beginning of a new school year or on the first day at a new school, the only things that matter are your background and your looks. Let me address looks first: Katniss and Peeta make an excellent first impression because of their fiery outfits and confident stance. Quite literally, people like these new guys because they’re hot. Case in point: all the tributes have to be publicly interviewed, and in hers, Katniss is sort of awkward and not very funny, but because the crowd already likes her they laugh at everything she says.

The interviews touch on high school’s blunt, non-subtle, brutal labeling of others; each tribute is reduced to one trait that is then enhanced and outrageously played up. There’s the sexy girl (named Glimmer, no less), the funny guy, the strong, silent, brooding type, and the buff, aggressive fighter. Peeta casts himself as the boy madly in love…with Katniss, who is understandably furious. But Haymitch tells Katniss she got a leg up: Peeta made her “look desirable.” Oh yeah, and Katniss got the most oohs and ahhs for twirling in her dress (more fire) than for anything she said. I can’t decide if the story is satirizing the placement of women below men or unintentionally—maybe even intentionally!—perpetuating it.

A big reason why first impressions are important is because a good one can secure a tribute sponsors. Sponsors are usually wealthy Capitol residents who want to see their favorites live a little longer, and as such they can pay to deliver supplies to the arena. Katniss is worried about how she’ll do because she’s “not very good at making friends.” By the true definition of friend that’s a false equivalency; by a more cynical high school definition of friend it’s fairly accurate. Sponsors aren’t real friends, just followers.

Tributes from different districts follow the same conventions as the different types of high schoolers, like in the interviews but slightly less exaggerated. There’s the nerd, the jock, the artsy girl. In school there might be a few cliques that form from these categories, but in The Hunger Games it’s just one. You’re in or you’re out, and from the beginning, Katniss and Peeta are out. The clique surrounds the Careers, tributes from Districts 1 and 2 who have grown up training and volunteer for the Games. The Careers are high school’s ‘popular kids.’

The Careers—the popular kids—are made out to be enemies, people to hate, from first sight. The first time we see one is while Haymitch is congratulating Katniss and Peeta on their parade performance. He pauses, and the camera angle switches behind the two of them to show Cato, a tall, blond young man, wearing gold, sleeveless armor engraved on the shoulders with a feather pattern. He looks condescendingly over at the District 12 cohort. He and the rest of the Careers are characterized as arrogant, condescending, possessive, and territorial assholes who revel in the hunt and the kill. They taunt (Clove, the classic mean girl, torments Katniss with filthy sarcasm as she’s ready to kill her), and bully (Cato snaps the neck of a no-name supply pile guard).

And they’re all beautiful white people. Most members of the Career clique are sexualized or gender-typed—white, buff, pretty, fair. Everything about them is reduced to a blunt, unsubtle extreme. Flirting, too: Cato heats his sword in a fire until the tip glows red-orange only to spit on it, prompting Glimmer to scoff “please,” with a giggle. He might as well just say, “Look, I have a big dick.” Further, almost all of the interactions between the tributes would be normal in a high school—passive-aggression, clique drama, and crushes.

If the popular-kids-as-enemies concept is true, Katniss becomes more interesting as a protagonist. For the conflict to work, she would have to be unpopular, or have qualities the popular kids didn’t, and still be relatable to the vast majority of teenagers. Those qualifications seem contradictory, but there is a solution. The short version of her entrance to the Capitol and the Games goes like this: she bursts in on the scene with her stunning appearance, the Careers see her as a definite threat, and they go after her almost immediately. She’s the hot new girl. It’s a sad truth that if new students are quiet, unassuming, and physically average, they won’t really be noticed. But if they are confident, if they stand out, and yeah, if they’re hot, they won’t be immediately written off.

Still, even the hot new girl is no match for the popular kids. Katniss is immediately targeted and never has the upper hand. She’s just trying to avoid direct conflict with the tribute clique. The girls and boys alike in the clique argue repeatedly “she’s mine!” When the movie reaches its climax, in the form of a Gamemaker-sponsored “picnic,” the lunchroom, Clove is straddling Katniss, hands around her neck, choking her out, wielding several knives, bullying, taunting, teasing her about Peeta (“Where’s lover boy?”), and she can’t do anything but try to turn away, struggling, to no avail.

The social crisis The Hunger Games makes vivid comes to a head in that scene: the mean girl is holding the hot new girl down at knifepoint in the lunchroom, taunting her to pure hatred, and the new girl is helpless. But if we are to like the movie’s end, the mean girl must be vanquished. The solution comes in the form of a classic rescue. Thresh comes barreling out of the woods and tears Clove off of Katniss. Livid, he violently slams Clove twice into the wall of the Cornucopia, and she collapses, dead. And we like it. The whole audience feels a vindictive pleasure—to put it crudely, we’re all thinking FUCK yeah!

So teens are flocking to the theaters to watch the mean girl get beaten to death. That’s much more plausible a reason, to me, than to watch anti-capitalist propaganda or a warning that our civilization is heading for a Lord of the Flies-esque brawl. It’s not a particularly original fantasy, but we lap it up every time because the fantasy solution really isn’t good enough. It doesn’t actually solve anything, it just holds the problem off for two hours. Bullying is a real, rampant horror. One out of twelve teens still attempt suicide. Most of the time, there is no Thresh—the real-life Clove is still there. And somehow high school still seems like a game.