Our most prized possessions are our identities. Whether we know it or not, we treasure the ability to understand and define who we are, and how we relate to other people. So what happens when a threat is posed to our identity, to what we think makes us unique? Cultural theorist Theodor Adorno posits that since industrial society started mass-producing culture, art – valued for being an outlet of individual creativity – is in danger of becoming all the same. The sameness does not stop at art – the industrial production of culture for mass-public consumption indicates that we, as individual as we might feel, are just part of the mass consumers, all conforming to standard molds of taste and interests. So we’re now faced with the depressing thought that the culture industry is churning out mind-numbing entertainment, enabling us to not think too hard for ourselves and just go along with everyone else. But if you look closely enough, a glimmer of hope can be found in art that manages to present an alternative to the monotony.

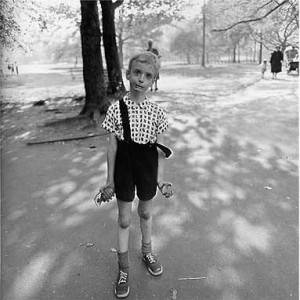

Diane Arbus, a self-proclaimed “photographer of freaks,” presents us with art featuring people on the fringe of society exposing and embracing their “abnormalities.” Skeptics of cultural ingenuity (and believers of cultural sameness) might ask: isn’t she commercializing and exploiting people with physical abnormalities? What makes her work different from Freak Shows common in the 19th century or American Horror Story: Freak Show – culture that draws on and exhibits “biological rarities?”[1] Arbus was met with disgust when her work first came out – people could not understand why she chose to capture ugliness (many refused to even call it art). Reception of her work has drastically changed and is now widely revered for giving a voice to underrepresented people and outcasts. But this same claim could also be made of American Horror Story: Freak Show. Arbus’ work goes deeper than just exhibiting striking abnormalities like Freak Shows, or even breaking down the stereotypes and boundaries of “normal” like American Horror Story: Freak Show. Her photographs force viewers to confront their own anxieties about how others perceive them and examine their own happiness and paths of existence. Arbus’ art shares real stories – the stories of her subjects, of herself the photographer, and of any view who engages with it. Her work is not broadcast across the country at a scheduled time every week, but if you do happen upon her subtle art you will be rewarded with an alternative to the sameness of entertainment.

In an optimistic and most positive assessment, American Horror Story: Freak Show is like any piece of popular art aiming to break down the stereotypes of an outcast group. The show details the lives of a group of “freaks” trying to stay relevant in the dying Freak Show industry. The ostracized characters because of their physical differences and who are not immediately relatable – but crafted with dimensions to identify with. Storylines are interwoven with dramatic human emotions that tug at your heart strings: you root for the “freak” and “non-freak” who fall in love; you empathize with freaks learning to love and embrace who they are. Boundaries and associations of the label “freak” are broken down by a character that is outwardly and physically “normal” – and has led an economically and socially privileged life – but has clear psychological “freakishness” and disadvantages. The line that distinguishes “freaks” from “non-freaks” is even further blurred in our minds.

While American Horror Story: Freak Show redefines normal and promotes tolerance, it engages you with characters whose realities are evidently distant from your own. You might temporarily lose sight of this distance as you sit enraptured for sixty minutes, but are abruptly brought back to reality and left sitting in front of a screen. Any real emotional investment you had7 in the story has suddenly dissipated. And this viewing experience is probably just what you wanted from the show. It evoked exciting and fearful and dramatic emotions for sixty minutes at the end of your day. The word “entertainment” in German translates literally to “underholding,” or “what holds you under” – the show has held you under its spell for the perfect amount of time to “relax”, and then releases you back to your “real life”. You might establish a connection with the storyline and characters, but it is a detached connection at best.

And this is where we see Arbus’ work diverging from commercialized “photography of freaks” – she has crafted a story that cannot just be turned off and release you back to reality because it is reality – the reality of the actual subjects, the reality of the photographer behind the camera, and the reality of you – the viewer.

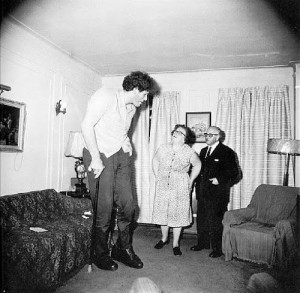

Arbus’ work and American Horror Story: Freak Show are different manifestations of art in their intended purpose and end product. The writers and directors of American Horror Story: Freak Show create characters for mass audiences to connect with and storylines to increase viewership; Arbus’ work portrays real people and their stories. Arbus does not view her art as the end in itself – the subject is more important than the actual photograph – and the experience of connecting with her subjects is in a sense the art. In some of her most famous works such as “A Jewish Giant at Home with His Parents in The Bronx, N.Y. 1970,” or “A Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street, N.Y.C. 1966,” subjects reported one of the most striking aspects of Arbus’ craft was how she invited and expected her subjects to get to know her in the vulnerable way she was getting to know them. Arbus firmly believed that she and her camera were temporary guests entering the lives of her subjects: “‘I work from awkwardness,’ she said. ‘By that I mean I don’t like to arrange things. If I stand in front of something, instead of arranging it, I arrange myself.’ That arrangement is about humility: you don’t change the subject, the subject changes you.”[2] She acknowledged that she was entering existing lives and that those lives existed independently of her art. In American Horror Story: Freak Show, the story and the characters – and our attachments – are contained and bound to the art itself. The “realness” of engagement with the show ends not far from where it began. Arbus’ art rests on the premise of natural, empathic, genuine human connection and interaction. When you can have that, do you even need mind-numbing entertainment?

Her attitude towards her art allowed her to access her audience in a unique way because it begs viewers to confront their personal insecurities and fears. Arbus proposed a theory of the “gap between intention and effect” –her photography makes viewers consider the gap between what we want people to see and what cannot helped but be seen by others[3]. She made her art with the intention of advancing her subjects’ and audience’s understanding of themselves and the way they relate to others. Reception of her work also illuminates fears that our society has: expressed discomfort exposes layers of anxieties about our own freakishness and abnormalities, as well as the discomfort we feel from seeing someone else so exposed and vulnerable. Sometimes viewing her photographs feels unnatural – like you’re looking into a window of someone’s life that you shouldn’t be, and that reaction stems from our inclination to push back and close the door on unconventional intimacy and vulnerability.

American Horror Story: Freak Show and Arbus’ photography demonstrate common interpretations and cultural value. It is very possible that for some shared viewers, each piece of art achieve the same effect. There are probably people who might not think twice about what a photograph of “a giant with his parents” has to offer them. But in the midst of the cultural industry infiltrating our minds with sameness, we have to take advantage of the genuine art that is simply commenting on the basic human condition. So while this is on one hand may seem like a love letter for Arbus’ work, it is a call to take Arbus legacy in stride. She understood that the art itself was a merely closing the distance between us and the people we share this world with.

[1] “Freak Shows.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, n.d. Web. 18 Mar. 2016.

[2] Kim, Eric. “11 Lessons Diane Arbus Can Teach You About Street Photography.” N.p., 15 Oct. 2012. Web. 18 Mar. 2016.

[3] “The Photography of Diane Arbus.” The Inkling The Photography of Diane Arbus Comments. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Mar. 2016.us/