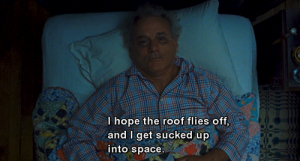

We have all been told that laughter can be the best medicine. Researchers have connected laughter with a physical response that significantly improves your mood, and have concluded that if we laugh more, we’ll be happier. But the research can also be interpreted to support the opposite claim. Laughter cheats happiness because it temporarily tricks your body into thinking you are happy; it is a vehicle that enables you to avoid confronting pain and suffering. Adorno claims that the mass production of consumer culture “replaces pain, which is present in ecstasy no less than in asceticism, with jovial denial. Its supreme law is that its consumers shall at no price be given what they desire: they must laugh and be content with laughter.” Adorno’s claim is devastating. Laughter – what we take as an outward expression of happiness – actually indicates unhappiness. What does this mean for those of us who have laughed – as I presume many of us have – at least five times today, and expect to laugh at least five times tomorrow?

Laughter and misery can converge in the form of stand up comedy. Comedians utilize their ability to reach a wide audience to present social commentary, drawing on historic and contemporary social patterns and inequality for material. Dave Chappelle’s famous comedic commentary on racial and gender inequality in America repositions the interplay between laughter and misery: he tries to use laughter to attack suffering head on. What does it mean to laugh at a joke rooted in misery and unhappiness – both for our society and our own personal happiness?

In his stand-up routine “Killing Me Softly,” the audience’s laughter validates the truth to Chappelle’s social commentary, acknowledging the general unhappiness present in our society. During one bit, Chappelle describes how his white friend has no fear of the police – and has even asked a policeman for directions while completely intoxicated – while Chappelle hides out of fear of persecution. The audience laughs because they can, in some capacity, imagine this happening; we understand that racial inequality manifests in police treatment of civilians, and we laugh. Our laughter exposes Chappelle’s commentary as rooted in some real reality – if the joke is so out of left field that it is incomprehensible, we wouldn’t laugh. So what moves us to respond to this commentary by laughing? If we are laughing at an expression of unhappiness and pain, then this laughter cannot be an expression of happiness. Can it be possible that we are actually deriving pleasure from suffering and misery?

John Limon offers a different reason for why we laugh at pain in his book “Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America.” He argues that the art of stand-up revolves around the abject, or the incorrigible parts of our identities that strain our sense of self. However, another layer of abjection emerges from his analysis: Limon describes laughter as the “social equivalent to pain” because it minimizes the weight of your abjection. Laughter can temporarily relieve your incongruous understanding of yourself, or your desire to rid yourself of the role in your life that you believe has become your only character.[1] In other words, comedy and laughter – by revolving on the subject of the abject – abjects, or casts off, pain. Furthermore, “the specific benefit of laughter is obliviousness. In this respect, laughter has a strange intimacy with pain…the use of laughter to combat disease must have something to do with the capacity of pain and humor for creating exclusive, hence mutually exclusive, worlds.”[2] Humor and pain are spheres that push each other away – so using humor (which we are inclined to do because it feels better than pain) – keeps pain at a distance.

The argument that laughter pushes pain away does not necessarily place laughter in a negative context – trading laughter for pain seems like an obviously easy trade to make. However, laughter in the context of stand-up comedy and social commentary has negative implications because, as Limon explicitly says, it makes us oblivious; laughter allows us to brush away specific ideas that are too important to ignore. It allows us to push away pain that cannot just be pushed away because it is so deeply systemic and important to understanding the individuals and communities of our society. The pain and suffering that Chappelle draws on for material should not be ignored because it the pain of ourselves and the pain we feel for others.

So how does humor distance us from our pain and what implications does this have for our happiness? In their research entitled “Humor Theories and the Physiological Benefits of Laughter,” Julia Wilkins and Amy Janel Eisenbraun explore the physiological basis of the humor theory – which can be broken down into three main segments: the relief theory (humor is outlet for tension in order to provide relief), incongruity theory (laughter from contradictions between expectations and experiences), and the superiority theory (laughter derived from sense of supremacy over others).[3] Their research supports the relief theory and suggests that one of the main reasons we value humor is for its physiological relief of tension: laughter is a social coping mechanism that allows us to distance ourselves from pain and unease.

Stand-up comedy has many moving parts: the comedian on stage, the audience comprised of individuals, and future viewers. Laughter in the context of stand-up is social. Dave Chappelle described a situation about being brought “to the ghetto by a cab driver” and finding himself in the middle of a drug deal. I (watching on a computer), along with the audience, laughed at this segment, even though I have definitely never been in that situation, and I would guess other audience members could also not explicitly relate. The joke creates a divide between those who share this experience with Chappelle and those who don’t. I found myself laughing because the joke repositioned me in relation to Chappelle and other audience members: I was made aware that my privilege has kept me out of this situation, but that the same could not be said for Chappelle, or likely other audience members. The joke exposes a division of experiences and privilege, which creates tension. Each audience member may each be partaking in complex laughter for different reasons, but we are laugh together in order to release tension.

Laughter can also distance us from pain felt by our society by marginalizing our role in the specific issue of the social commentary. During his routine, Chappelle often switches from playing caricatures of stereotypical black and white men. The humor theory’s third facet – the theory of superiority – would suggest that audiences laugh at his attempt to satirize a classically racist white male out of a sense of superiority. The racism portrayed seems so explicit that it seems impossible to fathom acting that way yourself. The group laughter denotes Chappelle’s portrayal of racism as ridiculous – we laugh because we think it’s just an exaggeration, and hold ourselves to a higher moral standing than the actions and attitudes of the caricature. We believe that racism as Chappelle portrays it is not a real issue for us because we are above it. The distance between us and the reality of suffering grows.

In this sense, humor positions negative situations in a more positive perspective, and thus it also enables us to hide from the truth of the social commentary. Although comedians like Chappelle try to utilize the lightheartedness and inclusivity of comedy as a platform to address important social issues, comedy actually pads the issue because we as a society are not ready to just address them head on. In the police-officer routine mentioned above, Chappelle says with a straight face, “we, as black people, have very legitimate reasons to fear the police.” Cue audience laughter. The cold and simple truth – sandwiched in the context of a stand-up comedy routine – produced laughter; if the statement had been delivered in a different arena, it would be considered far from funny. Laughter takes away the sting and discomfort of seeing the truth in plain sight because the truth.

Another avenue to humor and pain is asking what would happen if we did not laugh. If we don’t laugh at the joke that satirizes racism – if the room just has an air of solemn silence – then the weight of that joke and it’s roots in real suffering crash down on us. The realness of the issue hits hard and fast…unless we laugh. Our laughter instead reduces the heaviness, acknowledging the situation as “not that bad” – we detach ourselves from the responsibility of actually trying to do something about changing the issue. Even if we were ready to see the truth of the joke, laughter enables complacency in the face of social inequality. And so it becomes even more evidently clear: laughter – even as a means of attacking pain straight on – cheats us out of happiness by distancing us from our pain and enabling us to not put in the work to make ourselves happy.

But we never have to face these truths head on because we have laughter. Chappelle seemed to come face to face with this realization when he decided to cancel his show Chappelle’s Show in 2005, during the peak of its success. He realized that his show – and caricatures of black stereotypes – gave audiences permission to laugh at real suffering. He revealed on Oprah that he felt like “some people understood exactly what he was trying to say with his racially charged comedy…while others got the wrong idea.”[4] When he puts a line or joke in his show, it is immediately released into the public hands; using humor for social commentary can have effects out of the comedian’s control. The joke or caricature can be taken out of the context of the comedian’s greater social commentary and lose its greater significance. It becomes relegated to the comedic realm with very little chance of having any real agency over social change. The very real suffering that served as the basis of the joke is marginalized and allows people to be complacent about the misery.

Comedy has become a socially acceptable platform to present grievances with social orders and hierarchies; but why can’t an explicitly bold and polite presentation of social commentary be just as acceptable? Sure – it is tense when someone comes out critiquing and exposing privilege – but maybe if we resisted the (natural) urge to diffuse the tension and just sat with it, we could actually be moved to make changes. Now seeing that Adorno’s arugment holds truth, are we going to remain content with laughter as a consolation prize for happiness? Perhaps we prefer the immediate (physiological and psychological) gratification of laughter – and pushing pain away – over putting in the effort and hard work it takes to reconstruct and initiate social change. So, are you ready to give up laughter for the sake of a life worth living – for yourself and generations to come?

Works Cited

Limon, John. Stand-up Comedy in Theory, Or, Abjection in America. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2000. Print.

Wilkins, Julia, and Amy Janel Eisenbraun. “Humor Theories and the Physiological Benefits of Laughter.” Holistic Nursing Practice 23.6 (2009): 349-54. Web. 20 Apr. 2016.

“Chappelle’s Story.” Oprah.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2016. http://www.oprah.com/oprahshow/Chappelles-Story#ixzz46WSC4qTH

[1] Limon, John. Stand-up Comedy in Theory, Or, Abjection in America. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2000. Print.

[2] Ibid, 104.

[3] Wilkins, Julia, and Amy Janel Eisenbraun. “Humor Theories and the Physiological Benefits of Laughter.” Holistic Nursing Practice 23.6 (2009): 349-54. Web. 20 Apr. 2016.

[4] “Chappelle’s Story.” Oprah.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Apr. 2016.