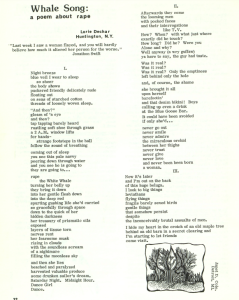

Vicki Breitbart and Beverly Leman’s “The Women Who Take Care of Children: Why Child Care” was published in the January 1971 issue of Up From Under. This educational essay highlights the benefits of universal, free childcare.

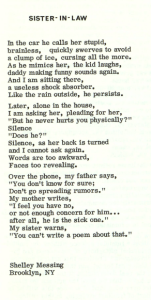

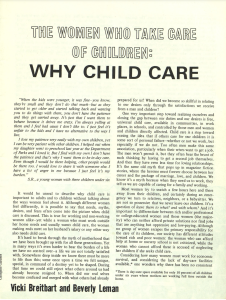

Second-Wave feminists urged society to share the responsibility of motherhood with women. Prior to the movement, society shamed women for their desire to be more than mothers. By refusing any support for mothers, society kept women in their socially-defined role. Second-Wave feminists quickly realized for women to gain any freedoms, not only would they have to realize their strength, but also society would have to change with them. In the editorial statement of the February 1971 issue, Up From Under’s editors discuss the paradigm shifts required to change the narrative around motherhood. They explain “society has a responsibility to provide universal, free childcare” (Albert et al. 4). Universal, free childcare is child care accessible to all families with children younger than school age. In this issue of Up From Under, the editors feature essays that expand on the importance and implications of universal childcare. For example, in their article titled “The Women Who Take Care of Children: Why Child Care,” Vicki Breitbart and Beverly Leman proclaim “our very important step toward realizing ourselves and closing the gap between our duties and desires is free, universal child care…it is a step toward erasing the idea that if others care for our children it is some sort of personal failure” (Breitbart et al. 6). Feminists urge society to give all women access to childcare, allowing mothers to prioritize something other than the needs of their family and children. Free universal childcare would empower women to explore their identity beyond motherhood. Additionally, in the essay, they emphasize that free universal child care would promote society’s success (Breitbart et al. 7). Women could more easily contribute to the workforce, while also, raising their children –the next generation of workers. Through the creation of universal childcare, society could share the responsibility of motherhood, and, also, create a more successful economy.

The New York Times featured Claire Cain Miller’s “How Other Nations Pay for Childcare. The U.S. Is an Outlier.” on October 6, 2021. This article discusses a modern look on accessibility to childcare. Also, it highlights the benefits of childcare in a COVID-19 world.

Although Second-Wave Feminism vehemently advocated for universal childcare, even today, the United States still does not adequately support families. In Claire Cain Miller’s New York Times article, published on October 6, 2021, titled “How Other Nations Pay for Child Care. The U.S. Is an Outlier.,” she highlights the modern child care problems. In the article, Miller features Elizabeth Davis’s comment about spending on child care in the 21st century. Davis, an economist studying child care at the University of Minnesota, states “we as a society, with public funding, spend so much less on children before kindergarten than once they reach kindergarten yet the science of child development shows how very important investments in the youngest ages are, and we get societal benefits from those investments” (qtd. in Miller). Even today, the United States does not provide access to child care. Not only does this problem perpetuate women’s subjugation to house work and child care, but also it prevents children from developing skills they will need for success in future schooling and work. Miller explains “studies in the United States have also found that subsidized child care and preschool increase the chance that mothers keep working, particularly low-income women” (Miller). Many families rely on the incomes of both parents. Without access to adequate, free child care, women many times stay home, leaving their families without this integral source of income. The cycle of a limiting motherhood continues, affecting low-income women more than anyone else. Although the US has increased accessibility to child care in some ways, it still does not do enough.

Sources:

Albert, Marilyn, et al., editors. Up From Under, vol. 1, no. 3, 1970, pp. 1–57.

Breitbart, Vicki, and Beverly Leman. “‘The Women Who Take Care of Children: Why Child Care.’” Up From Under, vol. 1, no. 3, ser. 1, 1 Feb. 1971, pp. 10–14.

Miller, Claire Cain. “How Other Nations Pay for Child Care. The U.S. Is an Outlier.” The New York Times: The Upshot , NYTimes , 6 Oct. 2021, Accessed 11 Dec. 2021.