Discussions of domestic violence and sexual assault require emotional maturity and an understanding of the weight that such conversations hold. Oftentimes, participants of these conversations feel detached or disconnected from the subject matter; however, the National Sexual Violence Resource Center reports that 81% of women experience sexual assault within their lifetime. In efforts to comprehend the fact that every person knows a victim of sexual assault, an excerpt from a 1979 issue of Essence, a popular magazine specifically aimed toward Black women, can be analyzed. That is, Joyce White writes in volume 10, issue 2, of Essence, “When I asked a social worker friend if she knew of any battered women who would be willing to talk to me about their experiences, without a moment’s hesitation she said, ‘That shouldn’t be any problem. Ask any of the women you know.’ I was shocked after talking to scores of women I realized the phenomenon was as common as she’d implied, and that it affects all of us” (126). She may not be your sister, your best friend, or your partner, but it should not have to take “she could be your…” for you to recognize the need to take action to cease the epidemic of domestic violence and sexual assault.

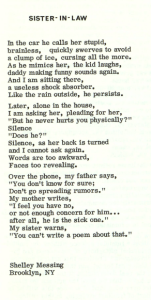

The prevalence of domestic violence across the nation grew in attention during Second Wave Feminism. In a 1975 issue of Women: A Journal of Liberation, Shelley Messing’s poem “Sister-in-law” epitomizes the strains on familial relationships that domestic violence yields.

“Sister-in-law” poem by Shelley Messing, featured in Women: A Journal of Liberation vol. 6 no. 2.

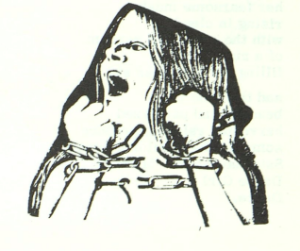

This image is from Women: A Journal of Liberation vol. 6 no. 2, and is situated next to the poem titled “Sister-in-law” by Shelley Messing.

Since this poem is written by someone who knows a victim of domestic violence and verbal abuse, it clearly exemplifies the notion that victims are closer than they appear. Additionally, the title of the poem implies that the victim is the writer’s sister-in-law, and thus the abuser is the writer’s brother. The most striking lines of this poem are in response to a question of whether or not the writer’s brother physically assaults the writer’s sister-in-law. The lines read, “Silence, as her back is turned / and I cannot ask again. / Words are too awkward, / Faces too revealing” (14-17). These lines demonstrate the complex relationship that exists between someone who is abused and someone who has unintentionally learned of the abuse. The pain, most likely too strong for the sister-in-law to bear, has been unveiled by the writer in an unspoken nature, as the abuse is not explicitly stated. The writer’s expression of her brother’s abuse defies the wishes of her family, which is apparent in the lines that read:

My mother writes,

‘I feel you have no

or not enough concern for him…

after all, he is the sick one.’

My sister warns,

‘You can’t write a poem about that.’ (Messing 22-27)

By writing this poem, the writer amplifies the voice of her sister-in-law as a means to illustrate the importance of sharing her story.

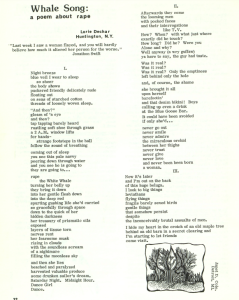

The idea that every person knows a victim of sexual assault or domestic violence has further been confirmed by the Me Too movement, which originated in 2006 and grew in popularity in 2017. The Me Too movement serves as a means for victims of sexual assault to find support within a community that values a discussion of recovery from abuse. The following is a reading of a slam poem that articulates the importance of writing and sharing one’s story of sexual assault:

Blythe Baird’s most significant lines from this poem embody the importance of expressing one’s emotions surrounding abuse. She states:

Sometimes I worry I write too much about assault

I worry this is too heavy a burden to carry

I worry I am putting too much responsibility on you, the listener

But when I talk about my trauma, I am not asking you to carry it or relieve me from it

I am just asking for it to not be too heavy for a conversation.

This experience takes up so much space inside of me

And this stage is the only place I can let this trauma live outside of my body. (Baird 0:28-0:57)

This effectively expresses sentiments felt by women sharing their experiences during the Me Too movement, as a sense of camaraderie continues to develop when one allows trauma to be “live[d] outside of [one’s] body” (Baird 0:54-0:57).

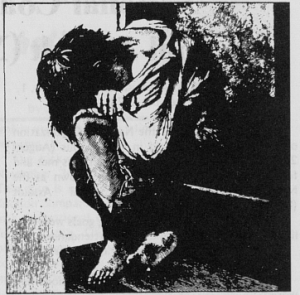

This image depicts a participant at an organized event for the Me Too Movement.

Sources:

Baird, Blythe. “Yet Another Rape Poem.” YouTube, Button Poetry, 6 Nov. 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OVA8FMp-_L4

Essence vol. 10, no. 2, June 1979.

“Four Years Later, Most Believe Women Have Benefited from the #MeToo Movement – AP-NORC.” AP, 19 Nov. 2021, https://apnorc.org/projects/four-years-later-most-believe-women-have-benefited-from-the-metoo-movement/.

Messing, Shelley. “Sister-in-Law.” Women: A Journal of Liberation vol. 6, no. 2, 1 January 1975, p. 19.

White, Joyce. “Women Speak!” Essence vol. 10, no. 2, June 1979, p. 126.

Women: A Journal of Liberation vol. 6, no. 2, 1 January 1975.