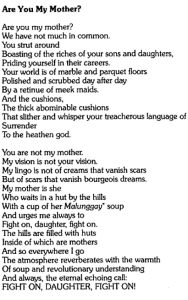

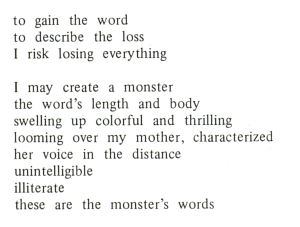

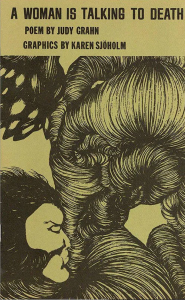

While lesbian publications largely aimed to form communites of readers and to create a sense of unity through bringing shared experiences to light, some queer writers intended to educate all women and destigmatize and broaden perceptions of lesbianism. For example, in Judy Grahn’s “A Woman is Talking to Death,” which was the opening piece of literature in the December 1973 issue of Amazon Quarterly (2), she strived to break down straight misconceptions of queer love. The poem is composed of nine sections, and the third section is especially powerful in its depiction of the nuances of love between women. The poem is set up as an interrogation between a woman and a questioner who could be reasonably interpreted as the patriarchy or death. It seems as if the woman is being evaluated on her “purity” based on her answers to questions that ask about her relationships with women. Even though the questions are clearly targeted at incriminating the subject, she admits to everything that she is interrogated about, but in a holistic way that the inquirer was not expecting. When the woman is asked if she has ever kissed any women she says that she has kissed many women, and goes on to speak about the people she has kissed: “women who recognized a loneliness in me, women who were hurt, I confess to kissing / the top of a 55-year-old woman’s head in the snow in Boston, / who was hurt more deeply than I have ever been hurt,” (1).

The cover art for Judy Grahn’s “A Woman Is Talking to Death” was a lithograph by Karen Sjöholm, which was published by the Women’s Press Collective in 1974.

When the inquirer asks his final question, which is “Have you ever committed any indecent acts with women,” the subject admits to her “indecent” acts, which she identified as the ways she let her fellow women down. This poem eloquently depicts the nuances of love and life, while destigmatizing queer love. Although there is no response to these questions that would have actually made the woman “guilty,” by answering the questions in an unexpected manner, she forces the reader to judge her based on her life experiences instead of solely her sexuality.

Work Cited

(1) Grahn, Judy. “A Woman Is Talking to Death by Judy Grahn – Poems | Academy of American Poets.” Poets.org, Academy of American Poets, https://poets.org/poem/woman-talking-death.

(2) Laurel, et al. “Amazon Quarterly.” Amazon Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 2, Amazon Press, Dec. 1973, pp. 1–76, https://jstor.org/stable/community.28032325.