The detrimental impacts of child abuse must be examined within the context of Second Wave Feminism in order to fully comprehend women’s role within the family and how such abuse shaped familial structures. In issue 26 of Country Women from 1977, Janet Newell’s essay “Once A Battered Child, Always A Battered Child” epitomizes the notion that childhood abuse negatively impacts familial structures, and more specifically affects the role of women within the family. Newell specifically discusses her victimhood as a survivor of childhood abuse, as her mother was her abuser. With that being said, she simultaneously validates the abuse she endured while also being cognizant of her mother’s victimhood as well. Newell writes, “My mother was a victim too: a victim of frustration in the role of wife and mother of two children and, as it turned out, at times the sole or main support of the family. She was also a victim of the war my father went off to and came back from traumatized three years later, another victim” (22). This excerpt allows Newell to then discuss the sociological impacts of abuse, as she writes:

The conditions of family life in America are such that the possibility for violence is always there. The hierarchical, patriarchal structure is set up in such a way that the frustration and anger at tension and stress created in the family and at work can be passed down through the pecking order. When the child acts out the pain and confusion, then the tension breaks into a pre-abuse or abuse situation. (23-24)

This excerpt exemplifies the need to dismantle the patriarchy in order to cease the continuation of abuse within families. This is further supported in an Aegis issue from 1978, in which a writer for the periodical states,

I think it’s just like violence against women. We can prevent some individuals from getting abused and we can prevent some individual abusers from abusing. But it’s such a cultural problem and a social problem that it needs much more work than just working with the family to make sure they don’t abuse their kids. I think that it’s in the process of starting but I see us having years and years and years of cultural standards that need to be broken. So I don’t think we’ll ever eliminate abuse against women or kids until we look at how our culture sets it up, and that’s a big project. (“‘Daddy Said Not to Tell:’ Dynamics of Sexual Assault – Part II” 10)

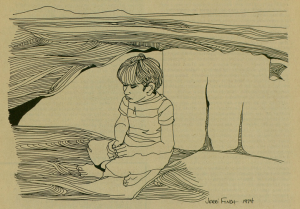

This image is from issue 26 of Country Women, published in 1977. Jerri Finch drew the image in 1974.

As the son of someone who has experienced abuse, I find that my experiences are effectively articulated in Del Martin’s Battered Wives from 1976. The statement reads, “…Staying with my husband means my children must be subjected to the emotional battering caused when they see their mother’s beaten face or hear her screams in the middle of the night” (130). Having called the police in the middle of the night, at the age of nine, in efforts to stop my mother’s screams, my emotional maturity has strengthened as a result of the abuse that occurred within my home. It is difficult to imagine the guilt that my mother felt while I was exposed to domestic violence; however, we must remind ourselves that victimhood should not coincide with guilt, and that my mother’s safety superseded my innocence. The “emotional battering” that I experienced was solely the result of one man’s actions, who encouraged my mother to “[…] suffer in silence, adding to [her] physical injuries an insult to the spirit that makes [her] believe [she is] somehow to blame for what has happened to [her]” (Bell 2).

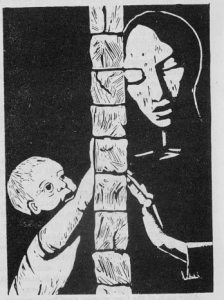

This image is featured within the November 1978 issue of Aegis, in the article titled “Daddy Said Not To Tell: Dynamics of Child Sexual Assault – Part II.”

As a society, it is evident that in order for child abuse and domestic violence that “emotionally batters” children to terminate, we must spread awareness about resources that are available to women and children. Barbara Meyers, in an issue of Aegis that was published in 1978, expresses sentiments of raising awareness by writing:

Within our culture we are told that whatever happens in the family is OK. If a man beats his wife it’s OK because it’s their problem. It’s a family problem and we’re taught to stay out of family problems. The lack of permission to talk about what goes on in the family contributes to peoples’ isolation and doesn’t allow people to get help for what’s going on in their families. (8)

Meyers uses key words in this excerpt like “permission” and “isolation” in order to demonstrate the fatality of honoring the sanctity of the home at the expense of the safety of women. This issue of valuing the sanctity of home is also apparent in the fact that martial rape did not become nationally illegal until 1993, and women could not open a bank account without a husband until the 1960s. Therefore, the legal context of men’s domination of women certainly depicts the abuse that women endured throughout history. Now, the emotions associated with abuse being expressed in the form of writing during Second Wave Feminism served as a catalyst to the dissection of the family dynamic that had hindered women’s stories of abuse from being shared. That is, writing served as a means to strengthen the voices of women and children who had been silenced for so long.

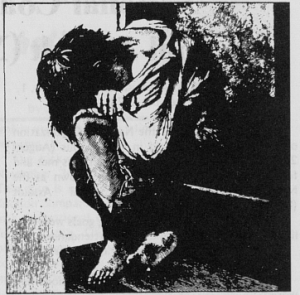

This image is featured within the November 1978 issue of Aegis, in the article titled “Daddy Said Not To Tell: Dynamics of Child Sexual Assault – Part II.”

Sources:

Aegis, November 1978.

Bell, Mary E. “Safe at Home?” Women: A Journal of Liberation vol. 6, no. 2, 1 January 1975, p. 28.

Country Women issue 26, 1 September 1977.

“Daddy Said Not To Tell: Dynamics of Child Sexual Assault – Part II.” Aegis, November 1978, p. 6-10.

MacLean, Nancy. The American Women’s Movement: A Brief History with Documents. Bedford/St. Martins, 2009.

Newell, Janet. “Once A Battered Child, Always A Battered Child.” Country Women issue 26, 1 September 1977, p. 20-25.

Women: A Journal of Liberation vol. 6, no. 2, 1 January 1975.