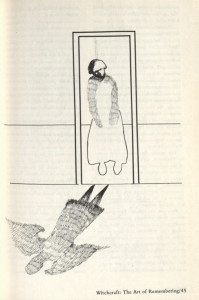

Unlike Lorde’s “Fantasy and Conversation,” Anne Sexton’s “Her Kind” directly confronts the image of the vilified witch. When listening to the live reading of “Her Kind,” the listener no longer hears an esteemed poet but is transported to a forest, sequestered by looming trees. In their wake, witches gather, singing incantations to transmogrify their world. Here, in this space, Sexton endeavors to show us that these are not mere women, but beings able to control forces of nature that so many fail to understand.

Throughout the poem, Sexton explores different figures that have been shunned by patriarchal society: the witch, a lonely old hag, and a woman on her way to her execution. The first stanza highlights typical deviant behaviors of witches, such as “haunting the black air” (18) or “dreaming evil” (18). While radical feminists attempt to reclaim the image of the witch and expel the negative stereotypes surrounding her, Sexton reinforces the mystical powers that so many feared. By doing so, she utilizes that fear and creates a kinship with those who feel misunderstood, the women who “[are] not wom[en] quite” (18). With Sexton claiming these negative images of women, she turns these stereotypes into something that feminists can use for their own gain. “I have been her kind” is woven throughout the poem, thus reclaiming the idea of the witch, and entreating others to do the same.

Source: Middlebrook, Diane Wood, editor. “Her Kind.” Selected Poems of Anne Sexton, by Anne Sexton, Houghton Mifflin, 1988, p. 18

American Poetry Archives. Anne Sexton Reads ‘Her Kind’ 1960. YouTube, YouTube, 19 February 2012, www.youtube.com/watch?v=btz8RZHSQ2Q.