Dew Panalee Maskati

The Apple way of life provides a spiritual path towards a utopia: one in which people and technology operate in harmony. In the years between Apple’s formation and the turn of the millennium, the relationship between the populace and computers was complex. The computer was seen as a testament to humanity’s ability and expertise — a wealth of information accessible at our very fingertips. It epitomises ideals of the Enlightenment that champion progress through rational thought and scientific enquiry. Indeed, Apple’s logo was deliberately chosen:

“In the Old Testament there was the first apple, the forbidden fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, which with one taste sent Adam, Eve, and all mankind into the great current of History. The second Apple was Isaac Newton’s, the symbol of our entry into the age of modern science. The Apple Computer symbol was not chosen purely at random, it represents the third Apple, the one that widens the paths of knowledge leading toward the future.” Jean-LouisGass, then General Manager of Apple France and former President of Apple Products, 1987:9-10 (Lam Pui-Yan)

The fruit of knowledge

But an understanding of the way in which computers functioned eluded the average consumer. Both tantalising and terrifying, computers acquired a mystical reverence from the populace in addition to being signifiers of hope. For some, this lack of comprehension turned into fear. This is why Apple’s image is arguably one of its most remarkable achievements: it managed to capture the spirit of invention whilst assuaging distrust of the unimaginably powerful ‘black box’. Its software is easier for the average consumer to operate than other brands’, thereby inviting trust. A sentiment commonly echoed by Apple aficionados is that Macs do not “fight back” in the same way that other computers do (Pui-Yan Lam). Consumers grow ever more reliant as smart technology becomes more ubiquitous. Apple devotees can now enshrine themselves in the iHome, a harmonious web of Apple products, a marketing strategy that only works because of the trust that Apple’s products invite. Although any purchase of an Apple product entails a subscription to its harmonious ideal, the loyal superfans exaggerate this utopian element and bring it to fruition — forming in effect, a subculture.

Apple’s image stands unique, because it is a corporate giant that has managed to reject corporate uniformity. The PC, on the other hand, is a computer for the businessman — who is going out of style. From the curved elegance of its minimalist aesthetic down to Steve Jobs’s distinctive black turtleneck and slacks, Apple manages to incorporate “play” and relaxation as one of its core values (Lam Pui-Yan). Apple’s new HQ, the second Apple Campus in Silicon Valley, is designed to epitomise these ideals. Once completed, it will become a site on which the opposing streams of the corporate world and hippie culture from the 60s merge. At this confluence we see an impersonal, profit-seeking foundation finding its expression in soft, organic forms that sing of spirituality and a countercultural edge. Curves are seen as harmonious and natural; the sharp and angular, dominating and evil. It was not designed to simply function as a workspace, but rather, to pioneer a new way of life. In the same way that Disney created their utopian bubble (EPCOT), the second Apple Campus is also meant to be a monument of sorts — to what a progressive future could be (Nikil Saval). In doing so, it counters the angular and sharp oppressiveness of the corporate.

An artist’s rendition of what the new Apple Campus will look like

Here is an extremely successful illusion at work: fans buy into Apple’s pioneering image with products that are meant to enhance their individuality — yet consumers are only offered a distilled selection of a rather small range of products. In contrast, Apple enthusiasts see Apple’s alter-ego, Microsoft and its founder Bill Gates, as profit-motivated corporate entities; consumers are merely part of a self-serving, industry-wide formula. This is because Apple founded itself on humanitarian values: its creators were not simply making boxes, machines or money; they were changing the world. Apple embodies the future — Bill Gates and Microsoft are giants from an oppressive past, to be toppled. To consume an Apple product is to participate in this movement — this philosophy of life — to lesser or greater degrees. Steve Jobs is not the ‘evil’ businessman in a suit, he is both at one with the consumers and their prophet.

And then Apple takes it one step further, overtly associating itself with creative genius. Richard Dreyfus’s poem became synonymous with the “Think Different” campaign: the poem utilises powerful imagery that encouragers rebellion through art, such as “here’s to the… round pegs in the square holes”, “they push the human race forward”, “while some see them as the crazy ones, we see genius”. None of the ads from the “Think different” campaign included any Apple products and that the participating celebrities were given Apple products and money to donate to causes of their choice; the producers took extreme care not to look exploitative. They also advertised in popular and fashion magazines — a bold move at the time — so as to merge style, artistry and practicality; Apple’s products bled out of the sphere of technology and business, and inserted itself into daily life. Here is a utopia in which human achievement sees no horizon, the individual in the masses is finally recognised, and conformity is rejected — one that can be carried around in a bag, a jeans pocket, the palm of your hand.

Sacralising the bond between human and technology has led to an Apple consumer base which John Schully, former Apple CEO, describes as a “cult environment” (Pui-Yan Lam). Scientific progress and the championing of rational thought undermines organised religion — so, to subscribe to scientific thought also means, for some, to confront a spiritual absence (Jeffrey Alexander). This brought a sense of emptiness to people’s lives. Apple capitalised on this feeling to become a spiritual medium by connecting its image with a progressive, utopian philosophy. The unusual outpouring of grief over Steve Jobs’s death — the size of which would have been more appropriate for a revolutionary icon or prophet rather than a successful businessman — is telling enough. Cyberspace has become a modern heaven of sorts, a dimensionless space which liberates us from the constraints of our body and geography: technology allows us to transcend social boundaries. A user on MacWorld says: “for me, the mac was the closest thing to religion I could deal with.” (Pui-Yan Lam)

A certain subset of the Apple fanbase has intimately and profoundly connected with Apple’s appliances. An ardent Mac user describes her physically affectionate relationship with her computer: “I mean there has been times that I hugged my computer and stuff like that. I have never hugged a PC.” (Pui-Yan Lam). Apple has this intimate appeal because Mac’s user-friendly system does not control users’ lives, but seems instead to expand them.

Perhaps even more stunningly, Apple’s most enthusiastic supporters have mobilised to form a subculture of their own. In 1997, David Every pioneered the MacKiDo website as a way to achieve enlightenment through the power of Mac. Every and other enthusiasts see themselves as saviours of humankind, promoting a radical philosophy of life accessible through consuming Apple products — whose light they believe other corporate giants are trying to extinguish. Notice the heroic, ego-stroking and spiritual language an Apple disciple, known as the Apple Jedi, employs:

If anything characterises the history of Apple and its users, it is their sense of community. Nurture it. Help strengthen it. Guide your actions in harmony with that which binds us all together unseen and yet keenly felt by the Apple Jedi. In the arrogance of its marketing and the nature of its tactics the Dark Side understands not these things, and cannot fight them. And so, it is in the deepening of this community that the greatest responsibility of an Apple Jedi lies, for it is in this power that Mac OS aficionados can find strength to triumph. (Pui-Yan Lam)

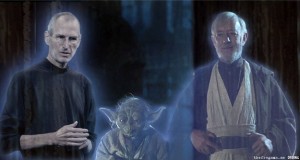

So here we have the phenomenon of the mac evangelists — Apple superfans who see themselves as warriors, heroes, and, most interestingly, Jedi. This association with Jedi is tied heavily with the consumer’s search for spirituality: here, it finds its expression in the reductive polarisation of the world of technology into ‘the side of the force’ — Apple and its consumers — and the “Dark Side” — other technology giants, PC users. The Apple Jedi’s mission, amongst this encroaching darkness, is to introduce people to the Apple way of life. And what is this way of life exactly? It is one in which technology is associated with an equalising power, diminishing social constraints and injustices.

The way of the force

“In this profane world, great business people, such as Bill Gates, who seek nothing but financial gains, are rewarded. However, the Mac devotees are looking forward to a utopia created by superior computer technology. In this utopia, people are judged purely on the basis of their intelligence and their contribution to humanity.” (Pui-Yan Lam)

These fans of Apple see computers as a “reflective medium,” crucial to the way in which they form their identity (Pui-Yan Lam). The computer is seen as an extension of the user’s mind, and the brand to which a consumer subscribes provides key insight as to what their life’s philosophy is.

The minority status of Apple fans before the turn of the millennium served to strengthen their subculture. PC users, who were the majority at the time, often derided Macs, calling them “toys” or “pieces of junk”. The harassment the Apple disciples endured seemed to have increased their sense of righteousness. An anniversary issue for MacAddict (now branded as MacLife), a magazine that promotes all things Apple, captured the spirit of the times perfectly:

“We’ve had enough. We’re tired of Apple being carelessly labeled as lagging, failing or dying. We’re tired of people maligning our Macintoshes. We’re sick of the slams, digs, and taunts directed at us by know-nothing PC hacks. It will stop. NOW. We will not surrender to the ‘inevitable’ of passively pray for the health of our platform. No, it’s time for revolution. Tell your family, tell your friends. Join us not just defending the Mac from attacks on all sides but also in an assault on the attitudes that provoke them. Join the Mac resistance.” (Pui-Yan Lam)

From the impassioned tone of this excerpt, it is obvious that Apple’s products stood for more than efficient and aesthetically pleasing technology. This is not only a call to protect Apple’s reputation, but also a declaration of war on the “attitudes” of the opposition: the ignorant consumers of corporations other than Apple were enabling a way of life that promotes business interests and subjugates the individual. By contrast, “mac resistance” is composed of people — “family” and “friends” — that are seeking to undermine the system that controls them.

But it is important to remember that these mac enthusiasts are only a subset of all of Apple’s consumers, and that their movement peaked before the turn of the millennium. Nowadays, Apple has become hip. In fact, the new wave of young consumers has caused older devotees to lament the lack of loyalty of the recent addition to their fanbase. Whilst Apple retains the utopian appeal it held from the beginning, the strong, progressive philosophy that came with the Apple way of life has receded; what seems to be left is the nebulous but attractive aura of a softly fading visionary movement.

Of course, Apple’s utopian image is not perfect. It’s products are becoming ever more similar, losing the visionary quality that made the brand so appealing in the first place: Wired magazine, in its critique of the iPhone 5, describes the smartphone as “completely amazing and utterly boring” (Mat Honan). And the ironic undercurrent that runs parallel to this essay’s argument, that completely undermines Apple and its superfans’ enterprise, is the fact that Apple is ultimately another profit-motivated corporate giant. The truly humanitarian values that may have inspired Apple’s creators have since become perverted: Apple’s utopia is simply an effective marketing strategy — packaging that cloaks Apple’s true profit-motivated interests. The illusion biases Apple fans against reality. Some are content to demonise Bill Gates, even though he is a well-known and respected philanthropist; meanwhile, Apple has recently come under fire for condoning exploitative practises abroad through Asian contractors. Apple’s products have always been a symbol of wealth and status, a utopian bubble only accessible to some, breeding a subculture founded on privilege.

Bibliography

Lam, Pui-Yan. “May the Force of the Operating System Be with You: Macintosh Devotion as Implicit Religion.” Sociology of Religion 62.2 (2001): 243. Print.

Alexander, Jeffrey. “The Sacred and Profane Information Machine: Discourse about the Computer as Ideology.” Archives De Sciences Sociales Des Religions 69, Relire Durkheim (1990): 161-71. JSTOR. Web. 19 Nov. 2016.

“MacKiDo – Mac Information & More.” MacKiDo – Mac Information & More. Web. 19 Nov. 2016.

Saval, Nikil. “Google and Apple: The High-Tech Hippies of Silicon Valley.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 28 Mar. 2016. Web. 19 Nov. 2016.

Honan, Mat. “The IPhone 5 Is Completely Amazing and Utterly Boring.” Wired.com. Conde Nast Digital, 9 Dec. 2012. Web. 19 Nov. 2016.