RJ Shamberger

Is race nothing more than a lived fiction? Or does race matter at all? I didn’t always know the answer to the question, then the world reminded me of my race and continuously showed me that I am in fact very different from those around me. The reminding moments did not always occur, and the vast majority of them have happened in the last five years of my life. Over the past half-decade, I have experienced two drastically diverse worlds that have taught me that race indeed does matter – and it matters a lot more than I would want.

Before I left for high school, race rarely crossed my naïve mind. Preceding that point, I started every day in my all black household and departed my majority black neighborhood for my ninety-nine percent black middle school. Everywhere I went, a comfortable sea of black faces continuously blanketed, and when anytime I looked into the mirror I saw myself – not my race. Early in my life, my parents ingrained in me the belief that I could be anything I put my mind to regardless of my situation – and looking back I realize that the faith manifested itself into a permanent destiny. I used to believe that the many problems people in my community and school faced were because there was something that they had or had not done in their lives. I was blind to the reason behind the issues those around me faced and quite frankly I didn’t care enough to learn. I honestly believed that my race played no part in whether or not I would live to see my dreams become a reality.

My understanding of American society remained fixed until I arrived on the campus of Deerfield Academy for my freshman fall term. Instantaneously, I was force fed every ounce of American racial relations as I struggled to learn the names of my elitist white classmates – the Rockefellers, the Waltons, the Kochs. I was mesmerized; however, I was further shocked to learn that there was only one black student in the senior class. Overwhelmed, I even went as far as opening my class representative speech with “I came here lost in a sea of whiteness,” only to replace whiteness later with the brilliance which seemed to be perfect synonyms. In America, whiteness is often characterized as mindfully brilliant and pure, while black is synonymous with unintelligent and vulgar. It was not until my time at Deerfield that I felt the pressures of being a black man in America. I realized that there is a blatant lack of equality among races because I knew that if my country was equal, then there should be more than one black student per grade in any preparatory institution.

From my personal experiences, I agree with the statement that race is nothing more than a biological lived fiction; however, since American society chose to live out the romance, race or its importance in society must not ever be neglected. If people never decided to bring attention to race and attach unseen characteristics to it then and only then would race not matter. Nevertheless, the United States chose for it to especially important. The most important event throughout the history of the United States was widespread of race-based slavery where millions of African-born slaves were brought to live as subordinates to the white majority. Initially, whites believed that racial slavery was justified as whites thought that they were biologically superior to the Africans. The justification was eventually outdated as slaves such as Frederick Douglass proved that individuals of African descent were fully capable of performing tasks that were deemed for whites only, yet it was not until decades later that blacks were no longer the physical property to whites. Although Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation granted blacks freedom, whites ensured that blacks were not treated as equal individuals for the following century as the battled for civil rights continued. As of today, the words of the United States’ Constitution states that blacks and whites are equals; however, these words are powerless to the actions of American history. There are bundles of systemic racism that remains in many institutions in the United States tended towards whites and the country as it stands is far from equal.

The film Boyz n the Hood expresses the daily and institutional struggles that various black communities in the United States deal with. The film takes place in urban South Central Los Angeles during the late twentieth century – more than one hundred years removed from the abolishment of slavery – and details the lives of three black youths – Tre, Ricky, and Doughboy – as they navigate the difficulties of their surroundings. First and foremost, the characters live in the ’hood as the title hints to, the term is slang for an impoverished majority black neighborhood. Each of the characters has complexities that set them apart, yet one thing stands constant – each of them is black. The presence of an entirely black cast provides an interesting paradox since the race is the continuous variable and it is logical to see how individuals can interpret the character’s varying reactions to their circumstance purely as poor decision making, yet I will quickly debunk that view. The film serves a definite purpose through telling the story of only black youths because many of the hardships that they face are mainly due to their skin color. Although there are times when character’s decision-making is vital, the film explains that the overarching problems at hand are due to situations that they cannot change and the systemically ingrained inequality in their community. One of such cases is when one of the three most famous characters, Ricky, is brutally murdered without much of any reasoning, and the immediate reaction by the fellow two protagonists, Doughboy and Tre, is to seek revenge.

The initial response by the two is entirely rational especially since Tre witnessed Ricky’s murder. Tre and Doughboy are angry following the loss of their best friend, and they are forced into a difficult situation knowing that the shooter could just as easily killed either of them. Enraged the two seek revenge and plan to kill the murderer, but after taking some time to contemplate his actions Tre decides not to partake in the attack. Meanwhile, I cannot condemn Doughboy’s revenge as he is doing what he must to survive even. In Doughboy’s community, there is a kill or be killed reality, and is nothing more than a product of a torn community which has been institutionally disdained by the United States. I see Tre’s actions in the scene as astronomically courageous as he, unlike his peers, fights his natural inhibitions. The issues the two of them face stem from slavery and systemic oppression within the country and we should hail each character should serve as examples of what happens daily to black men.

During the century leading to the time of the film, the United States endured an era in which blacks migrated from plantations, and to the horrors of their former masters’, imaginations to segregated ghettos and the Jim Crow laws. In his article An American Tragedy: The Legacy of Slavery Lingers in our Cities’ Ghettos, Glenn C. Loury outlines the roots of the marginalization of blacks throughout the twentieth century and its current effects. He states: “The United States of America, ‘a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,’ began as a slave society. What can rightly be called the ‘original sin’ slavery has left an indelible imprint on our nation’s soul.” “No well-informed person denies this, though there is debate over what can and should be done about it. Nor do serious people deny that the crime, drug addiction, family breakdown, unemployment, poor school performance, welfare dependency, and general decay in these communities constitute a blight on our society virtually unrivaled in scale and severity by anything to be found elsewhere in the industrial West.”[1] Loury briefly summarizes many of the issues regarding black in the United States, all of which stem from slavery’s existence. Also, Loury directly challenges anyone who opposes his reasoning as simply not well-informed or ignorant to the issues that blacks face on a daily basis.

The United States government has succeeded in its suppression of the black community because the system now replicates itself without direct government intervention. The film includes an important scene in which the character Furious – Tre’s father – directly addresses the underlining oppression through the placement of gun and liquor stores as well as purposefully devaluing black-owned property. In perhaps most powerful lines in the film, Furious bluntly states, “They want us to kill ourselves. The best way you can destroy a people is if you can take away their ability to reproduce themselves.” Furious further explains that the gentrification of black neighborhoods and the fact that blacks are not creating the problems in their communities. Blacks are not directly responsible for bringing drugs into their communities nor the presence of gun and liquor stores on every street corner. The black community has been set up to fail by those who are responsible for the key issues – the white majority.

In the United, race matters and it or the issues it presents cannot be ignored. However, there are still instances in which racial differences or interactions are misconstrued – usually by whites – and we need to educate those who believe that race is not as important as it on truths of the country that they live. Although I do not condone the violence of black communities, I do understand why it occurs, and there are multiple examples of dangerous white ignorance that I could address. I found a simple showing of implicit racial discomfort in an essay published in the late twentieth titled The Negative Influence of Gangster Rap and What Can Be Done About It by Anthony M. Giovacchini. While attempting to break down rap music – of which he apparently doesn’t understand – Giovacchini incorrectly writes the lyrics and name of N.W.A.’s infamous Fuck tha Police. He instead wrote Fuck The Police and quoted the words: “Fuck the police coming straight from the underground /A young nigger got it bad ’cause I’m brown…”[2] Despite whatever point Giovacchini tried to make, he is clearly ignorant enough not even to get the song’s name or lyrics correct. More so, he commits the cardinal sin of using the real n-word, instead of nigga which is the right words. The n-word that he states is much different than the other term as most blacks refrain from ever mentioning it, and the significance of the disparity is expressly race-related, as one pertains to what others called blacks in a derogatory manner while blacks casually use the other.

As I have contemplated the significance of race in the United States over the course of my life, I now realize that race is important and I cannot ignore it. The black community has long endured many hardships because of their race, and I as a black man am a part of their struggle for equality. Thus, the duty I share with my fellow black people is to educate those on the truths of our situation in the country and prevent individuals from continuingly propagating obscene arguments that race does not matter – because it does and it stands at the core of many of the issues blacks in America face.

[1] Loury, Glenn C. “An American Tragedy: The Legacy of Slavery Lingers in Our Cities’ Ghettos.” Brookings. The Brookings Institution, 28 July 2016. Web. 16 Dec. 2016.

[2] Giovacchini, Anthony M. “The Negative Influence of Gangster Rap And What Can Be Done About It.” The Negative Influence of Gangster Rap And What Can Be Done About It. Ethics of Development in a Global Environment, 4 June 1999. Web. 16 Dec. 2016.

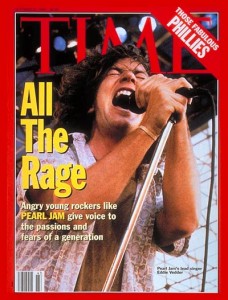

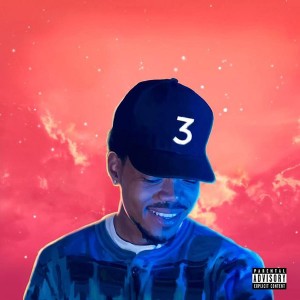

Grammy nominations and winners are widely debated and argued year after year. Someone is always left out and someone undeserving, so some believe, wins. Hundreds of experts review the nominations and a long, careful voting process takes place. The Grammy Award for Rap Album of the Year is presented to “honor artistic achievement, technical proficiency and overall excellence in the recording industry, without regard to album sales or chart position.” Previous winners have included Kendrick Lamar (2016), Drake (2013), Lil Wayne (2009), and many others who may or may not have been deserving. With the Grammy’s only a few months away and so many amazing albums being released this year, debates for which one is the best have already begun. Although the nomination committee claims it doesn’t regard alum sales as criteria, the album must be sold commercially through a record label to be nominated. With this being the case, there is one rapper who will never be nominated.

Grammy nominations and winners are widely debated and argued year after year. Someone is always left out and someone undeserving, so some believe, wins. Hundreds of experts review the nominations and a long, careful voting process takes place. The Grammy Award for Rap Album of the Year is presented to “honor artistic achievement, technical proficiency and overall excellence in the recording industry, without regard to album sales or chart position.” Previous winners have included Kendrick Lamar (2016), Drake (2013), Lil Wayne (2009), and many others who may or may not have been deserving. With the Grammy’s only a few months away and so many amazing albums being released this year, debates for which one is the best have already begun. Although the nomination committee claims it doesn’t regard alum sales as criteria, the album must be sold commercially through a record label to be nominated. With this being the case, there is one rapper who will never be nominated.