Very early on, I believed. These memories are faint, but I still remember praying aloud every Sunday for a parking spot, at my mom’s request, while my mom drove us around the cramped alleyways of Taipei. I asked God for help whenever I lost something, which I often did. I prayed with my mom before bed. We prayed together when I was diagnosed with a severe case of scoliosis and when we couldn’t find my cat. Although I was never that dedicated—going to church and reading the Bible were never fun to me—I did have faith.

My mother, a devout Christian, raised me in her non-denominational church in Taiwan. It was a thriving and close-knit community, but it might seem pretty unusual to most Christians in the US. We didn’t celebrate Christmas or Easter. Our meetings had no sermons, no priests or pastors, no pews—we all sat in folding chairs, people stood up spontaneously to pray or testify, and people would call on the name of Jesus again and again, with increasing fervor and volume. The adults and baptized teenagers would have grape juice in tiny little plastic cups. They practiced full-immersion baptism in a small bathtub in the basement.

I don’t remember exactly how or why I stopped believing in God; it happened gradually, so that when I was twelve, I came to the conclusion that God didn’t exist.

As a child, I understood prayer as a magic spell that was supposed to get me whatever I wanted. I quickly realized that my magic spell didn’t work most of the time, so I largely stopped praying. But I sometimes still made bargains with God when I was really desperate, when I really needed something to happen, rather than merely wanting it. “If you do this for me,” I’d beg, addressing a God I wasn’t sure was listening, “I promise I’ll worship you forever. Give me another chance, and I’ll give you another chance, even though I don’t know if you exist.” God promptly let me down. This sounds silly now, but for a child who was completely sincere, it felt like a serious breach of trust. I felt like God had betrayed me. I don’t think anybody offered me a different interpretation of prayer, one that went beyond asking a distant genie to grant wishes. Since that was my only conception of prayer, and prayer was my only relationship with God, I felt like God wasn’t there at all.

Apart from this feeling of abandonment, I started asking questions that my mom told me not to ask. I had always annoyed adults with my incessant inquiries, and as I learned more about the world, I developed many questions about our faith. It wasn’t even something as deep as the problem of evil; most of it was inspired by my mom and her church’s insistence that every single word in the Bible was the literal and perfect word of God. As a kid, I probably took that stance even further and more literally than they intended it, thinking that God personally wrote everything in the Bible and completely endorsed it. So when I began to read the Bible for myself, I wanted to know if God really ordered disobedient children to be stoned to death, whether all the people and animals in the world were produced from incest after Noah’s ark, and whether my mom really thought that wives must submit to their husbands (she said she did, even though she was far more assertive than my dad). Apparently, my burgeoning moral compass, curiosity about science, and refusal to accept patriarchal norms got in the way. Adults evaded and dismissed my questions, refusing to have an actual discussion about them. I was left feeling estranged and confused. What was supposed to be God’s writings and teachings began to seem ridiculous. Once I started thinking for myself, my childhood faith became untenable.

I grew bitter. I rolled my eyes when people praised God or read the Bible to me. I read novels during church, paying no attention to anything I was told. I made it clear that I didn’t want to be there. Even as my mom pressured me to go to Bible study and well-meaning cousins called me to read the Bible, I disengaged completely and inwardly scoffed at everything. In my stubborn pride, I considered myself above it all.

This was the first unraveling. My faith came apart completely; the belief system that my mom gave me had disentangled beyond repair, and could no longer hold me.

As I got older, I developed an even stronger contempt for God, for religion, and for Christianity in general. In high school, I realized that I was bisexual and fell in love with a female friend who became the first person I’d ever dated. During my honeymoon phase, I was so excited that I almost told my mom about my relationship, hinting at it while leaving myself plausible deniability. But my mom immediately started panicking, saying that she was worried that Satan was luring me into sin. (When I was little, she often shared interviews about how God saved “formerly” gay people from their wicked homosexual lifestyles.) At this point, I had already identified as atheist for years, and my mom’s hurtful reaction to my attempt to share my joy only solidified and intensified my distaste for Christianity. After all, my entire high school friend group was also queer, and I received the message that Christians condemned our very existence as evil. Because I had never been exposed to any other form of faith, I was convinced that all Christians held these beliefs—beliefs that not only made no sense to me, but seemed actively cruel and harmful to me and my loved ones. As time went on, my attitude went even further than atheism, into something that could be more accurately described as anti-theism. Thus, I wove together an impenetrable set of ideas about Christianity, all of which I strongly opposed, since I am passionate about justice and equality for women and LGBTQ communities.

During COVID, something strange happened. I had been stuck in a multi-year rut of meaninglessness and emptiness that only got worse when I started college. I felt lost. Something was missing, something deeper than what my therapists could address, and I was inexplicably drawn towards religious and spiritual life. It’s hard to express just how shocking and surprising this new development seemed to me, considering the deep aversion I held against anything Christian; my yearning for God was completely out of character. You must understand that I was stubbornly atheist to the extreme, having rejected God much more resolutely than I ever believed in God as a child. It pains me to admit this, but ever since my first unraveling, I looked down upon people of faith as delusional and narrow-minded, and I was filled with contempt and bitterness against Christianity.

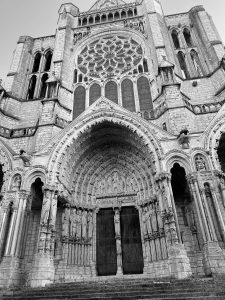

I thought I had left faith behind forever. And yet, there I was, nervously setting up meetings with the College Chaplain, Reverend Valerie, meetings that proved to be revelatory and cathartic. One Sunday, I worked up the courage to step into an Episcopal church service, a drastically different experience from the Sundays of my childhood. I emerged stunned and in awe of how much it spoke to my soul. There I was, daring to ask questions again, this time finding myself engaged in refreshingly open and honest dialogue with priests and chaplains. They patiently encouraged my curiosity and demonstrated that I—a queer person who is deeply distrustful of exclusionary religion—had a valued place in the community, and that my faith did not have to go against everything I stood for. In fact, I learned that my faith could bolster and ground my passion for justice and reconciliation. There I was, dismantling my preconceptions about faith with the help of kind peers and mentors, surrounded by people of faith who welcomed me just as I was, difficult questions and all. There I was, somehow feeling God’s loving presence again, as if for the first time.

It felt like healing—from the ways that religion had hurt me in the past and from my own misguided prejudices against faith. It felt like freedom.

As I tentatively dipped my toes into a very different kind of faith than the one I had known before, I felt pulled in, deeper and deeper; and the deeper I delved, the more alive I felt. Even though I was filled with wonder, I was also disturbed and perplexed at how this could happen. I was unraveling again; my cynical self was coming apart. If anything, this second unraveling was harder and more destructive than the first, since I was older now and had stronger and more deliberate convictions to untangle. This time, I had to painstakingly unravel the rigid intellectual edifice I had built up against faith for years. It was a long and arduous process, but I had help along the way—I read books that offered a radically different vision of faith than the one I was used to, I actively participated in progressive Christian communities online, and had long conversations with chaplains and priests. I learned that, for me at least, faith isn’t intellectual assent to a set of propositions. It isn’t about having absolute certainty; instead, I’ve found it to be more about trust and relationships and sacrificial love. At my current church, I learned that women and queer people could be, and are, in positions of leadership, bringing much-needed voices and perspectives to the church. I learned a new way to pray using the Episcopalian Daily Office and the Book of Common Prayer, which I have grown to love. I learned about various non-literalist ways of reading Scripture, discovering the vast and wonderful diversity in biblical interpretation and realizing that I didn’t have to shut down my mind and heart when reading the Bible. I learned that participating in my transformed faith, both communally and privately, brought me a special kind of joy and fulfillment that nothing else had been able to give. I learned to make peace, for the most part, with my mom’s expression of faith, even if I did not share it myself. Above all, I learned that God’s love is expansive—much more expansive than our selfish attempts to limit it. And Christ does not abandon his lost sheep.

As I see it, God called me back. It might be presumptuous of me to relate my experience with Paul’s conversion on the road to Damascus, but that was kind of how it felt. My old self would probably scoff at my current self in contempt and disbelief. Sometimes, I still ask myself: what have I become? And then I wonder: who else could do this but God? Who else could be the originator of such a comprehensive unraveling, such an unbelievable reversal and transformation?

Untangling the trappings of my previous worldviews was challenging, and I cannot possibly detail everything that I’ve come to see differently. I’m still changing and learning more every day, and I know I’m never going to have faith completely figured out. But to me, that’s the beauty and excitement of it—I am on a lifelong journey, with infinite possibilities of discovery and renewal ahead of me. This is a well that will never run dry.

Because I’ve had to unravel my inflexible systems of belief, my faith isn’t as tightly-wound as before. I don’t cling too hard to intellectual arguments about specifics of doctrine. But I do believe that my repeated unravelings made my faith more resilient than it ever could have been otherwise. Because I have already torn everything down, twice, my new understanding of faith is much more durable than anything I’d possessed before. I worked out what was important and what was not; I realized that faith wasn’t about weaving a tight and unchanging web of unassailable beliefs. Unraveling wasn’t something to be afraid of. In fact, it saved my faith. Here, I am reminded of the symbolism of baptism: “Therefore we have been buried with [Christ] by baptism into death, so that, just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, so we too might walk in newness of life” (Romans 6:4, NRSV). I see my departure and return to faith as such a dying and rising—my old self needed to be unraveled before I could discover a new way of life, itself a form of death and resurrection. For me, faith is about transformation. It is an openness to be changed, a willingness to see things differently and to do things differently. And so, paradoxically, the unraveling of my faith has been an indispensable part of my faith. If I may be so bold, I would even say that it has been a gift from God.

Abby Shen ‘24.5 is a Philosophy major. In a Record article, Abby shared that making Kant memes is one of her favorite things to do, and she wants everyone to know that her favorite tree on campus is the tree next to Schapiro near the First Church Congregational Parking Lot.