By: Danny Irvine & Nathan Szeto

No informed investor needs to be told that the movie theater industry is in dire straits with the rise of streaming services like Netflix, Disney+, & Amazon Prime Video, to name but a few. So why in the world would you want to buy stock in any movie theater chain?

The answer: You wouldn’t.

The answer: You wouldn’t.

Ok, great. But what about American Multi-Cinema, better known as AMC? It is the biggest movie theater chain in the world, after all. However, it didn’t get that way without taking on massive amounts of debt. This reality, coupled with decreasing revenue figures, market trends, and a poorly executed vision, has positioned AMC to be a poor stock pick within the near future, and a potentially catastrophic one in the event of a recession.

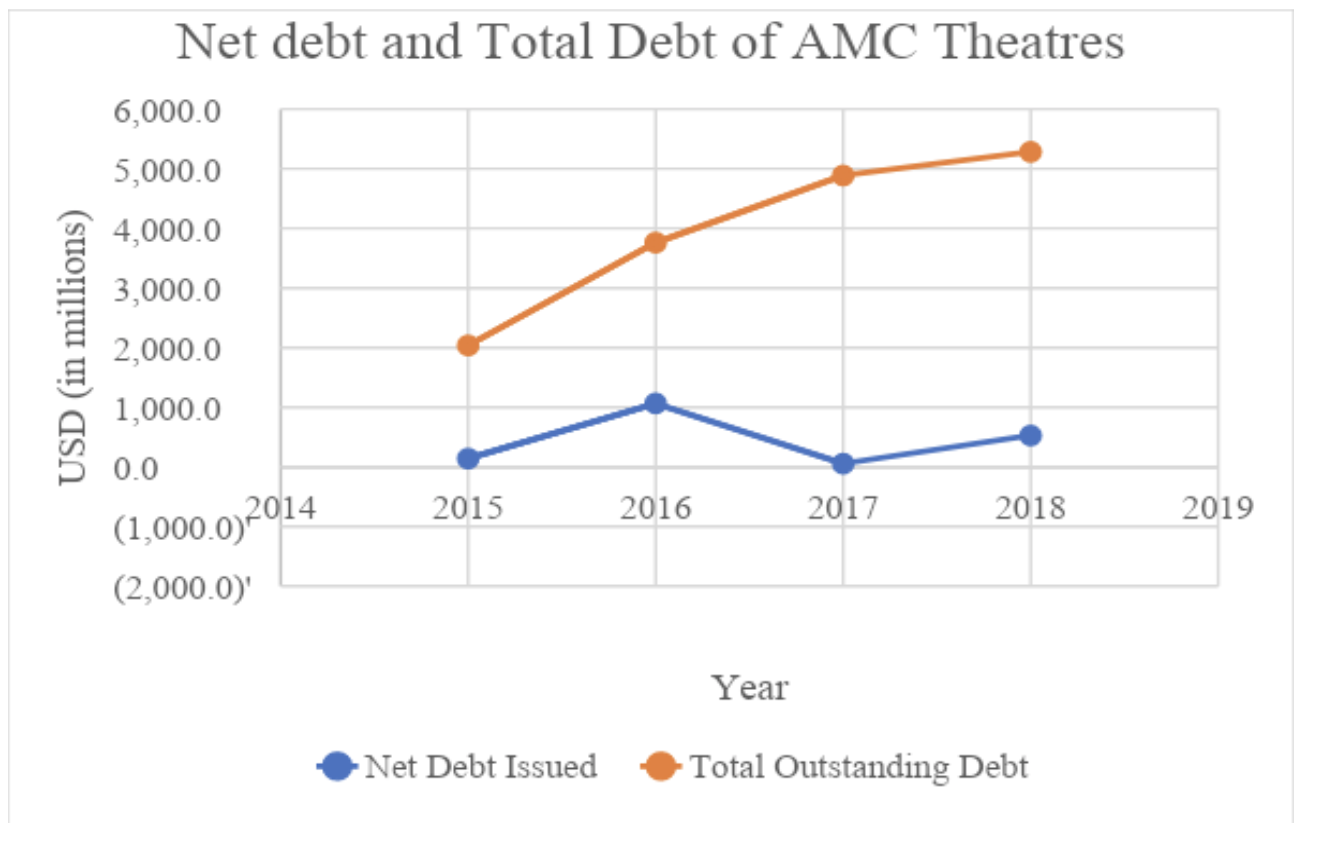

It may seem to the average investor that AMC has increased performance in recent years, and AMC’s yearly total revenues would support that assertion: in 2015, it produced $2.9 billion in revenue, and in 2018, it posted $5.4 billion, an increase of 86%. However, AMC’s revenue growth is deceivingly high because the company has not grown organically. Instead of committing to improving the movie-going experience for its customers, AMC’s corporate branch has embraced an expansion mentality. That’s right, the largest movie theatre company in the world is looking to increase their foothold in its stagnating industry via acquisitions. It’s important to note that we aren’t suggesting that AMC intends to monopolize, but rather it values quantity over quality of their theatres. Since 2015, it has acquired 700 theatres and has issued massive amounts of debt to fund these purchases. As can be seen in the chart below, the company’s total outstanding debt has exceeded $5 billion as a result. Seen in the same figure, the company’s net debt indicates the change in total debt. In 2016, AMC issued $1.75 billion in debt, all of which the company stated went to fund the acquisitions of movie theatre companies in Europe and Asia. In 2017, they made a large sum payment of $748 million to repay debt, but that hasn’t halted its persistently increasing amount of outstanding debt, which at the end of 2018 was $5.2 billion. Understandably so, being in the theatre business is very capital intensive, but the corporate acquisition strategy has jeopardized AMC’s future. The company’s financials reveal that its return on assets (ROA) percentage has been declining over the last few years. Since 2015, the ROA percentage has declined from 3.1% to 1.0%, with consistent decline each year, excepting 2018.

Figure 1: AMC Theatres total debt and net debt from 2015 to 2018

We’ve already mentioned that AMC is at risk of bankruptcy in the event of a recession, but what exactly do we mean? Given that AMC is already operating on very slim margins and is saddled with massive amounts of debt, it’s not too far of a stretch to believe that if the US economy experiences a recession, AMC will lose the ability to pay off its interest and eventually have to file for bankruptcy. For instance, with an operating income of $317 million and net income expense of $224 million, AMC has little room for error if their revenues drop even slightly. Also, the company’s net income margin percentage in 2019 was 0.2%, down from 9.6% in 2017, giving one a sense of just how slim the company’s margins are.

Think about it — is going to see the new Frozen 2 movie really a priority when you’ve just lost your job? (The answer should be no) Now multiply this sentiment by a few hundred million would-be moviegoers and you’ve got a bonafide crisis on your hands.

So why should we believe that a recession is imminent? According to a survey done of economists by the National Association for Business Economics, 3 out of 4 economists believe that the United States will experience a recession by 2021. Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, believes that prior to the 2020 election there is a 40% chance of a recession, up from 35% in February. These fears are supported by the ongoing trade war between China and the United States, as businesses scale back investment and struggle to maintain output levels. Lastly, within the last few months Treasury 10-year bonds fell below those of 2-year bonds. This situation, known as an inverted yield curve, has historically signaled that investors are reinvesting into safer assets and has preceded every recession since 1955. Even if these signals are all wrong, we are hard pressed to say there will not be a recession ever again. And when on hits, 2021 or 2025, AMC’s acquisition-fueled hopes and dreams will likely be demolished.

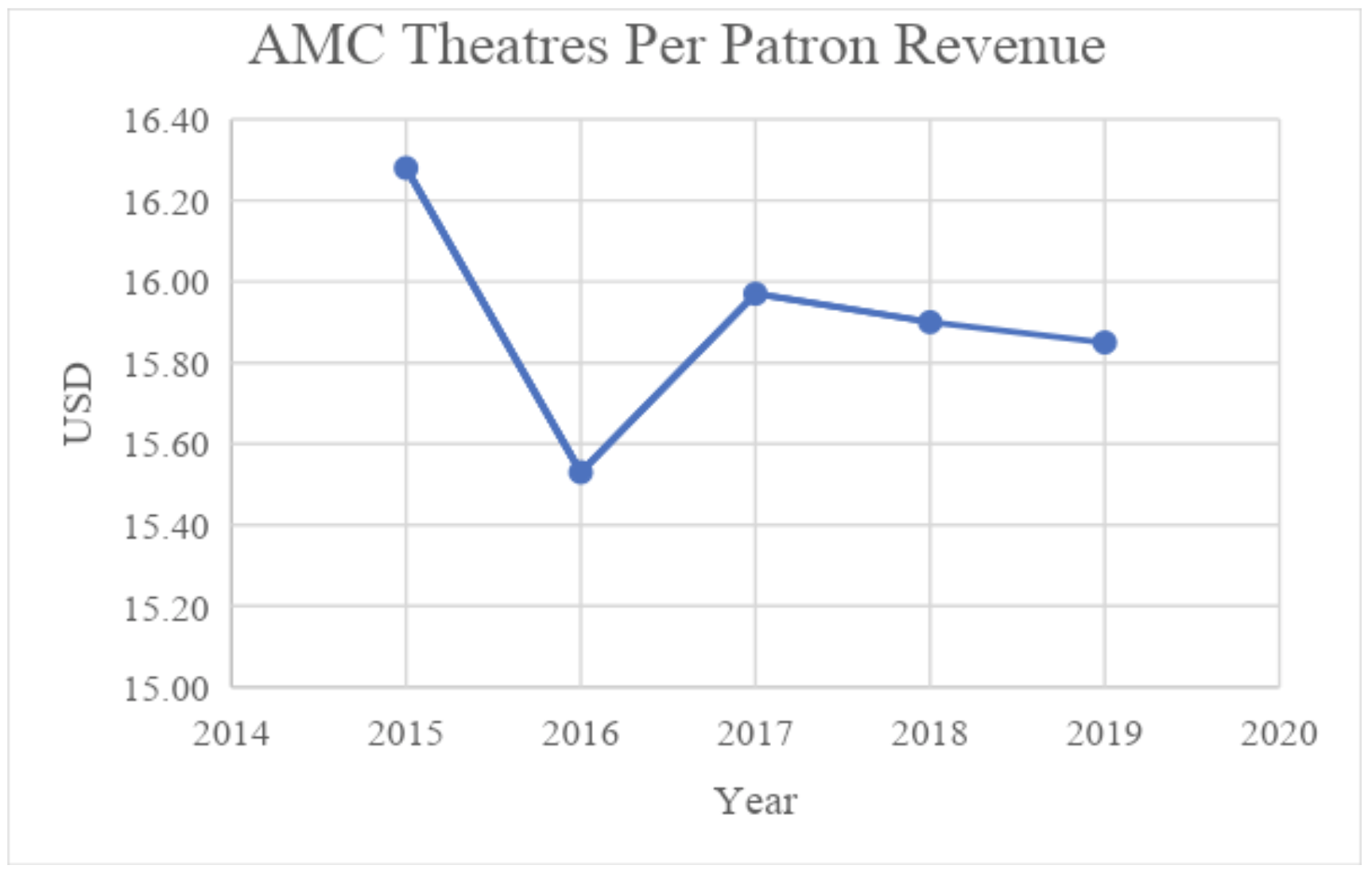

Figure 2: Per patron revenue from 2015 to 2019

AMC proponents would point out that the company has invested in the upkeep of some of its theatres to reduce asset depreciation. The most significant improvement was of 2,279 screens in 2018, with another 600 planned for 2019. Improvements include replacing traditional seats with fewer, but higher quality plush recliners, and improving dining options. This allows AMC to sell seats at higher prices with the goal of improving revenues per movie screen As of now, AMC improved over 2,200 screens, but they own 11,000 in total, leaving potential for a ton of depreciation and high capital expenditures (likely via even more debt) to occur as improvements perpetuate.

We looked at AMC’s revenue per patron because it better indicates its revenue change organically (controlling for acquisitions), compared to their total top-line numbers. The statistic reflects the average amount of money AMC earns from each customer through the ticket and food and beverage purchases Conveniently, it doesn’t take into account quantity of customers, so we can examine solely the quality of how AMC obtains revenue. Since 2015, there has been a 7% increase in the number of patrons choosing to buy food and/or a beverage (from 64% to 71%), suggesting that revenue per patron should increase. However, the overall trend is decreasing. Figure 2 shows the revenue per patron adjusted for inflation from 2015 to 2019. Although the margins seem small, there is a 75-cent decrease per patron. Considering the many thousands of people that visit AMC’s theatres each year, that 75-cent decrease will significantly wound organic revenue streams. Overall, the company has extracted less money from the customer over time, which they hope to offset with their new streaming service.

As if those numbers weren’t already depressing enough, the company has demonstrated no clear vision for moving forward best embodied in its decision to launch a new streaming service, as if consumers weren’t already inundated with other options. However, to add insult to injury, they have decided to structure it in the worst possible manner. Known as “AMC Theatres On Demand,” as uninspired a name if there ever was one, it is nothing more than a glorification of Google Play or iTunes, versus a proper streaming service. At least Google Play and iTunes admit that they’re not good deals. On top of the $15 annual membership fee required to use the service, each and every film and show has to be either rented for $3-6 or bought for $10-20. The movies are neither exclusive nor early access, as would be hoped for from the world’s largest movie chain. Even though the service provides in-theater benefits, value provided is still extremely poor and will likely fail to contribute to AMC’s bottom line meaningfully.

The launch of the streaming service is a symptom of a larger problem at the megacorporation that is American Multi-Cinema. That AMC’s leadership feels that yet another streaming service is necessary to raise profit margins indicates that it lacks the vision and creativity necessary to reverse the course of a company in an already dying industry. It reflects a management desperate to turn around a faltering company via uncalculated grasps for salvation.

The reality is that AMC is a company without ideas in a dying industry. Falling actual revenue per patron figures coupled with a massive debt load indicates that the company not only lacks future potential for growth but is extremely at risk of defaulting on its debts and filing for bankruptcy in the event of a recession. Worst of all, the debt AMC has accumulated has done little to grow its falling revenue.