Questions for Journal Reflection:

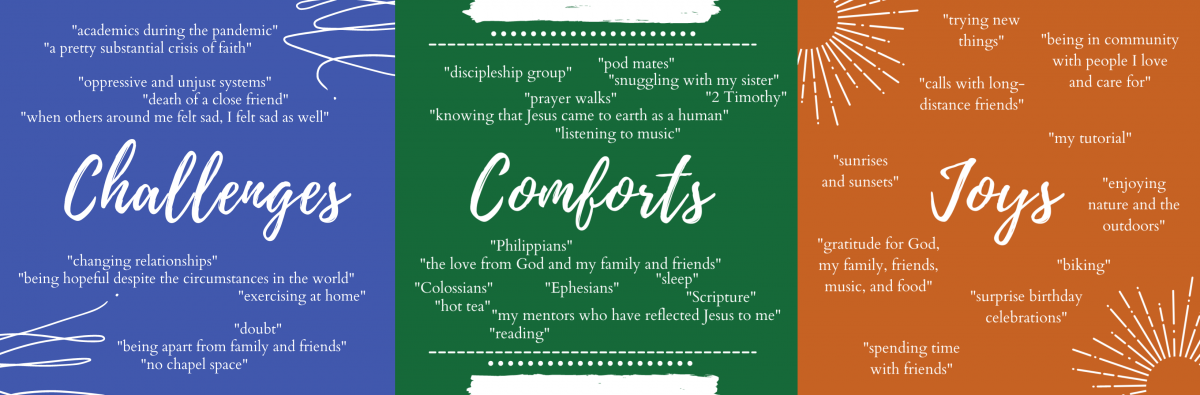

- Many of us have experienced the global trauma of the pandemic as a numbness. How does or doesn’t this resonate with you? Travel through any guilt you may be experiencing in response to this. Where does the pressure to respond in particular ways stem from for you?

- What memories of death do you have? Has the past year stirred up past grief? How has it changed your experience of grief?

- When we’re most honest, our own mortality often terrifies us. What about dying is scary to you? Have you had experiences where you experienced mortality as a gift? How does that shape this season for you?

- What are your methods and patterns of coping? What does healthy, holistic coping look like for you?1

Last January, I was heading down to Connecticut to visit a close friend of mine for the weekend. During the drive, it began to snow suddenly on a mountain road, and the car slipped on black ice as we moved downhill, resulting in the car crashing into a snowbank on the side of the road. Three airbags deployed. With my ears ringing and my heart pounding, I sat stunned in the passenger’s seat. My mind could not stop replaying the scene over and over again, each time fearing that the outcome in one of those scenes would be death.

By God’s grace, the two of us in the car survived with no injuries. In the several nights and days following this accident, my mind was fixated on what had happened, and I constantly ruminated on my proximity to death. It was so much closer to me than I had realized. Death could have met me on that road, and it would not have mattered whether or not I felt ready to leave this earth. With news of the coronavirus and its death toll also spreading during this time, I began to think more about my fear of dying and confront death as a reality that I would personally have to face one day.

This was not the first time I’ve thought about death. For years, I had lived with a debilitating fear of death. The fear of losing my life to some unexpected event, the fear that my life would be lost too soon, my years wasted to an accident, a mistake, or a simple oversight. Whenever I entered uncharted territory, I would always be thinking of the different ways I could die in that moment. As my paranoid mind raced through hypothetical possibilities of death, my heart would beat faster and my breathing would become heavy. Death was terrifying. It was, for me, the epitome of suffering and evil.

Yet when I began to actually wrestle with my proximity to death and process my fears about dying, my thoughts on death started to shift. I realized that death itself was not what scared me. It was what came after death, and not knowing exactly what came after death, that was truly terrifying. What I believed would happen after death greatly influenced my reaction toward death.

Having worked out a personal understanding of death and dying is a crucial factor in deciding how you want to live your life. Dr. Lydia Dugdale is a professor at Columbia University who recently published The Lost Art of Dying. In an Instagram Live before the release of her book, she noted, “There is no way to die well if you don’t give any thought to the fact that you are mortal.”2 Although death may be a somber and avoided topic of conversation, the reality is that all of us will one day face death. What you recognize and accept about this inevitable truth will change your understanding of life.

If you believe that there is no afterlife, it might be important for you to pursue everything you want to on earth before you die. Death is the end of existence. If you believe in an afterlife that is determined by how good of a person you were on earth, you might try to strive toward goodness in your thoughts, words, and actions. Death is the time of ultimate judgment.

As a Christian, I believe in the God who has overcome death and its judgment over us. Jesus came to earth in the form of a human being and chose to die on a cross to redeem our brokenness through His sacrifice. This death reconciled the separation between God and humans so that we could be in relationship with Him. Yet Jesus did not remain dead. God asserted His ultimate power over death when He raised Jesus from the grave. For those who believe in Jesus, death no longer condemns; instead, it ushers in new life. Jesus transformed death from an executioner into a gardener, and living in fear of death is to doubt this victory.3

This is why Paul in his letter to the Philippians can boldly declare, “For to me to live is Christ, and to die is gain. My desire is to depart and be with Christ, for that is far better.”4 When I live with faith that there is something better for me after death, I am freed from the fear of dying. Dying no longer symbolizes an end but rather a beginning of an eternal life with Christ. This hope frees me to fully enjoy each moment of my earthly life without worrying about when, where, or how I will die. The certainty of death instead becomes a reminder that my time on earth is finite and therefore something to be cherished while I am here. My life takes on deeper meaning as I am encouraged to live my life in hope and not in fear, looking ahead to that time when I will be reunited with Jesus.

Living without the fear of dying, however, does not mean that my life is void of death’s reminders. Death is woven into the pattern of our lives. As we journey through life, we encounter analogies of death that remind us of the ultimate end. Endings and goodbyes, breakups and departures; these are all experiences that reflect the character of death. Consider the death of a way of life that changes the way you interact with others, or imagine the death of a former worldview that brings you to see the world in a new light. In this age of COVID-19, there are many people in the world experiencing death or its parallels. We are suddenly being thrust into uncertainty, confronted with abrupt ends of life and ways of life.

Yet if God has already transformed the fear and uncertainty of our earthly death into the hope of new life through His victory over the grave, I know that He will also use the other ends we face in this world to usher in a better life. Death and analogous endings can seem full of uncertainty. Similar to how a seed sown deeply into the earth is first surrounded by complete darkness before it emerges into the light, the uncertainty that we face now may simply be the growing pains of a new life. In time, I trust that God will bring us all into a more whole, more beautiful world.

FOOTNOTES:

1 Riley, Cole Arthur. “MORTALITY | Lent III.” Patreon, 28 Feb. 2021, https://www.patreon.com/posts/mortality-lent-48013497.

2 Veritas Forum [@veritasforum]. Conversation with Lydia Dugdale. Instagram, 9 Jul. 2020, https://www.instagram.com/tv/CCZD4eRgD-c/.

3 Keller, Timothy and Kathy Keller. The Songs of Jesus: A Year of Daily Devotions in the Psalms. Viking Press, 2015, pp. 149.

4 Philippians 3:21, 23, ESV.