The 21st Century Fox logo fades to black as an Apollo spacecraft lands on the moon. An anthropomorphic cat, Scratchy, and an anthropomorphic mouse, Itchy, emerge from the spacecraft. Evoking another moon landing, Scratchy proclaims: “we come in peace, for cats and mice everywhere.” When the dramatic music stops playing, Itchy grabs an American flag and stabs Scratchy through the chest and beats him to near-death. In short order, Itchy returns to earth a hero, is elected president, and, when he discovers that Scratchy survived the attack, ‘accidentally’ launches the entire nuclear arsenal.

So begins The Simpsons Movie. Given the the traditions of Simpsons oeuvre, developed over nearly 30 years of television episodes, the choice to begin with Itchy and Scratchy is both telling and completely unsurprising. The entire series is rife with slapstick and low humor that connects closely to a host of early cartoons. But that first sequence also elides quickly into a scene in which Homer breaks the fourth wall, allowing Homer—and the film—to point out the ridiculousness of charging real audience members to watch a television-adapted movie, but he also points out the ridiculousness of charging audience members to watch a television-adapted movie that features a television-adapted movie:

Boring! … I can’t believe we’re paying for something we get for free on TV. If you ask me, everybody in this theater is a giant sucker, [pointing towards us] especially you!

The gag works because of its satirical observation and because it happens while breaking the fourth wall. And the “Itchy and Scratchy” movie, like the main series shorts, works because of its slapstick humor in the vein of Monty Python and Charlie Chapman. Together, these comedic techniques satirize the film industry, its relationship with consumers, cartoon violence, and The Simpsons themselves—all within only a few minutes.

The grotesquerie of the opening sequence invites the viewer to connect the Simpsons to a host of lowbrow humor and, in this way, to the “carnivalesque humor” described by Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin. In examining the work of François Rabelais, Bakhtin draws a connection between the “grotesque and scatological” jokes of the French humorist and the antics of Medieval carnivals (Duncombe 82). For Bakhtin, these carnivals upend social structures, placing the fool in the place of the king, and the king in the place of the fool” (88). “In this inversion and “temporary suspension … of hierarchical rank,” Bakhtin argues, participants “were considered equal during the carnival” (88). The satisfactions of this kind of inversion, according to Bakhtin, support a kind of subversive humor, one centered around upending social dynamics and presenting “world[s] inside out” and “liberat[ed] from norms of etiquette and decency” (88).

The Simpsons clearly appears to share the sort of proclivity for subversion that Bakhtin celebrates—but the movie does not fully adopt a Bakhtinian understanding of humor. While The Simpsons Movie does employ carnivalesque humor, it too challenges it. In its gags, the film shows the strengths of carnivalesque humor, but the film also illustrates its limitations, particularly in relation to other comedic forms. By looking at the ways in which carnivals and carnivalesque humor succeed and do not succeed in The Simpsons Movie, some insight can be gained on how effective Bakhtin’s argument is in its totality.

The most authentically carnivalesque moments may be those that occur in “excerpts” from the Itchy and Scratchy Show. Consider the cold opening again. The opening sequence only provides a few-minute segment from the “Itchy and Scratchy” movie—but those moments are memorably graphic. In those two minutes, Itchy beats Scratchy to near death using a flag pole, leaves him to die on the moon, and—when it turns out Scratchy is still alive—launches the entire nuclear arsenal of the United States. The “Itchy and Scratchy” shorts in The Simpsons television show are characterized by similar acts of violence. In one short, Scratchy is fooled by a sign offering free money only to be neutered; in another, Itchy hooks up Scratchy to a cloning machine in order to kill Scratchy over and over again. These violent, yet humorous, scenes demonstrate some of the argument made by Bakhtin. Like Rabelais and the carnivals, The Simpsons use crass humor—in this case, through over-the-top cartoon violence—as a means of upending social dynamics and as a form of satire.

But are these moments authentically Bakhtinian? In his chapter in Leaving Springfield: The Simpsons and the Possibility of Oppositional Culture, William Savage argues that the effectiveness of the “Itchy and Scratchy” cartoons lie in their ability to satirize [many things] in their violence. “Itchy and Scratchy” plays off of the older Tom and Jerry, but it also critiques corporate culture, cartoon violence, in a knowing way that an informed consumer of culture would immediately recognize. There is an obvious subversion, of course, in which mouse triumphs over cat. But there is also a knowing confirmation in which “getting” the full joke is an affirmation of the viewer’s superior position. Read in conjunction with Bakhtin, Savage’s argument suggests that the satirical power of the “Itchy and Scratchy” cartoons lies more with the audience member, rather than the carnivalesque elements of the gags.

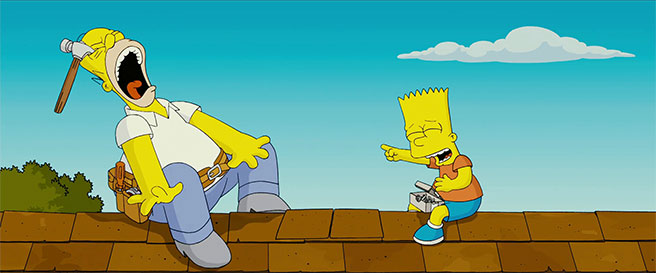

Of course, pure bawdy humor and comedic violence is a cornerstone of the Simpsons history, from Dr. Nick Rivera’s disastrous medical interventions to the endless radioactive anomalies—and worker injuries—caused by the nuclear power plant. But the most prevalent example of ‘grotesque’ humor appears in the relationship between Homer and Bart. In an early scene from The Simpsons Movie, Homer engages Bart in a game of dare, after Bart laughs at Homer, who unintentionally hit himself with a hammer in eye while repairing their roof. The two try to best each other by forcing the other to perform the most painful and humiliating tasks: Homer has to carry a pile of bricks on his back while Bart shoots him with a pellet gun, and Bart has to skateboard to a burger restaurant and back completely nude. The humor of the scene rests squarely on the physical pain the two inflict on to each other—but the scene also functions by subverting the standard relationship between a father and son. Homer and Bart are in turns overpowered by one another, in much the same way as the “Itchy and Scratchy” cartoons. And, unlike those shorts, the funniness of the scene is not predicated upon the viewer having inside knowledge: the subverted relationship between the father and son is implicit in the scene itself.

Nonetheless, it’s clear from this scene too that grotesque and physical humor alone is unable to subvert social dynamics. Homer remains the father figure in the film as in the television series and is responsible, ultimately, for the happy ending that keeps his family and his town intact. He may be a fool, but he also inhabits a position of “authority” that is never seriously shaken.

A Bakhtinian reading of The Simpsons is also challenged by the film’s central narrative, which exists outside of individual gags. In brief, the film tells the story of an averted natural disaster, one that is both caused by and ultimately resolved by everyman Homer Simpson. After an attempt by the townspeople of Springfield to clean-up their polluted lake, Homer drops a massive silo filled with pig feces into the lake—the lake is quickly covered in a bubbling green ooze and a giant skull-and-crossbones appears in the water. The head of EPA, Russ Cargill, decides to intervene by sealing Springfield under a glass dome. While the scenarios and scenes surrounding the glass dome offer opportunities for exploring carnivalesque humor, it is the interactions of Cargill with other characters that more so capture a Bakhtinian argument. Cargill gives the president—here Arnold Schwarzenegger—five sealed envelopes, asking him to choose one at random. Later on, Cargill—after being foiled by Homer and Bart—claims that there are “two things they don’t teach you at Harvard … how to cope with defeat, and how to handle a shotgun.” But before he can shoot Homer and Bart, Maggie pushes a boulder onto him.

In each of these instances, a government official is subverted and undermined—the president is told what to do by an EPA official; Cargill makes fun of his Harvard education; and Maggie drops a boulder onto him. These are successfully subversive acts, surely, akin to examples that Bakhtin provides. In “Understanding Satire with the Simpsons,” Carl-Filip Florberger specifically highlights the connection between the Simpsons subversion of officials of varying kinds across its episodes in connection with Bakhtin:

- Bakhtin pointed out that carnivals in pre-Protestant Europe created a scenario in which “…hierarchies were temporarily suspended and even inverted, no insignificant thing in a society ruled by rigid social stratification attributed to divine will” (Bakhtin 1984b, 13). The Simpsons use this play with hierarchies to criticize the country, the government and also the company that owns them, FOX Network (Florberger and Lunborg).

There is, however, one unquestionably successful subversion in The Simpsons, executed by the character with the least power — an essentially carnivalesque moment. It is Maggie, the speechless infant heart of the Simpsons family, who saves the day by executing the coup de grace. It is Maggie who pushes the boulder that lands on EPA head Russ Cargill and prevents him from shooting Bart and Homer. What this suggests is that Bakhtin was right. While The Simpsons relies upon many kinds of humor to connect to its audience, the most powerful moments are when otherwise powerless characters—like an infant child, or a idiotic everyman—are able to do something powerful. Or, funny.