When it comes to the current state of the young adult fiction publishing world—a topic, granted, that does not occupy a significant position in the everyday thoughts of the average person—nothing has played a bigger role than the Harry Potter series, without which almost no one would be concerned with the genre. JK Rowling’s astronomical commercial success signaled to other writers that YA fiction promised the most eminence and wealth. As a result, the genre includes many more authors and novels worthy of critical attention than it did in the BHP[1] era. The Hunger Games series, by Suzanne Collins, comes along as another iteration of the so-called Harry Potter Effect, but is a more direct descendent of the Twilight saga, which is on the “adult” end of “young adult.” The commercial success of the series is hardly surprising given its components: a post-apocalyptic United States called Panem, a strong female protagonist, and an annual festivity—known as the Hunger Games—in which two dozen teenage “tributes” fight to the death on national television. Any of those three aspects could be a springboard for critical analysis, but I am going to focus on the first one and what it means for racial issues in the series.

The Hunger Games has elicited contrasting responses on the issue of race. A writer for The Atlantic says that the it, like others of the science-fictions genre, pushes racial issues to the back burner,[2] and a response to that article in Christianity Today contends that The Hunger Games does in fact bring up issues issues.[3] I am going to argue that these statements are both true. The series, in a feat that is both amazing and horrifying, recreates a segregated United States, but passes it off as a post-racial society that appears utopian in its lack of racial issues. How does it do this, you ask? Very carefully.

Ursula Le Guin famously said that science fiction is “not predictive; it is descriptive,” and The Hunger Games is verifiably descriptive in most instances. Collins herself has said that the inspiration for the novel came when she was watching news coverage of the war in the Middle East[4] and that the harsh, authoritarian government is a more extreme representation of George Bush’s failure to respond to the needs of American citizens.[5] The novel also recognizes income inequality of the time and magnifies it so that the rich—the citizens of the Capitol—are legally superior in that they are not required to volunteer to enter the Games.

However, the descriptive nature of the novel abruptly stops at the issue of race, minimizing racial issues through its narrative focus. The story follows (in first-person) Katniss, a teenager from District 12—former Appalachia. The district is socioeconomically divided between the coal miners from “the Seam” and the merchants in the town. Katniss, being a part of the former group, is very poor and, though we hear very little about the conditions of other districts, we are told District 12 is definitively the poorest and probably the most oppressed.[6] In dystopian fiction, the things that are, for lack of a better term, bad are the objects of the author’s concern. As one writer puts it, by making the white Appalachian workers the lowest class, the novel is “essentially saying, “Things could get so bad that people who look like Liam Hemsworth are now at the bottom, too!””[7]

Based on Katniss’s understanding of the districts, it is explained that District 11—located in the South and in charge of food production—is slightly better off than District 12, at least in terms of nutrition. This difference is important with regard to the novel’s characterization as dystopian: a world where Mississippi is not the poorest state is a utopia from that state’s perspective. The novel’s utopian treatment of the South goes beyond economic issues. Although District 11 is shown to be primarily black, it is implied, again through Katniss’s understanding, that the district faces less harsh rule by the Peacekeepers[8] than does Katniss’s district. Even though District 11 appears to be the only one with any black citizens, race never figures prominently in the politics of of Panem.[9] As evidence, Katniss seems almost “colorblind,” describing Rue, the female tribute from District 11, as looking exactly like her younger sister other than having “dark brown skin and eyes,”[10] details that would halt such a comparison today. Collins is clearly imagining a post-racial society and has for that reason had to edit—remove the racial issues from—real world events as she fictionalizes them. It’s hard to imagine that, in an authoritarian society based on the imperialist and discriminatory tendendcies of George Bush, whose inadequate response to hurricane Katrina led Kayne West to declare “George Bush doesn’t care about black people,” racism could have magically vanished. In crafting a dystopian criticism of the woes of a mid-2000 America, Collins left racial issues out of consideration, sending the message that those issues are not important.

With dystopian class relations and utopian race relations, the focus is the plight of the poor whites. As Mary C. Burke and Maura Kelly write, “the dominant narrative of The Hunger Games tells us that class and nation are the central axes of power and oppression.”[11] If we accept this series, being a critique of the Bush presidency, as having at least a slight liberal slant, then the emphasis on class complies with the liberal tendency to reduce “class to inequality in order to deflect attention from racial disparities,” as Touré F. Reed writes in Jacobin.[12] Despite her poverty, Katniss’s privilege—being white—means she is never responsible for her actions. After Rue dies in the Games, Katniss raises three fingers, a symbol of rebellion, to the cameras, prompting the viewers of the Games in District 11 to do the same and then break out into a riot.[13] The Peacekeepers respond with riot shields, clubs, and high-powered hoses in a crackdown that strongly resembles Bloody Sunday. Similarly, in the sequel, Catching Fire, Katniss gives a speech about Rue in District 11 and the residents put up the three-finger sign, leading to one of them being shot on the spot by the Peacekeepers. In both cases, Katniss is the heroic figure and the District 11 residents—the ones who bring her ideas of rebellion to fruition—receive the brutal retaliation of the government. Later, Katniss’s own district is nuked out of existence, but the attack happens outside the narrative focus and seems to spare most people that Katniss knows. Yet the novel (or film) does not criticize the disparity in treatment but instead seems to say that no matter which side you are on, the whites will be the leaders and the blacks will bear the physical burden. The narrative focus indicates a conscious choice to show the destruction of black bodies but merely mention the same fate for whites. These decisions indicate that racism is very much present, but on a representational level.

It is at this point that I should stop and address the contradiction that The Hunger Games both is and isn’t about race. Race, being a product of society and culture, is often riddled with contradictions, as Richard Dyer notes in “The Matter of Whiteness.”[14] In The Hunger Games, the plot pushes the idea of a post-racial society while the minute details—likely to be skipped or forgotten by the YA target audience—reveal that the society is actually closer to a more racially segregated past. In the words of Burke and Kelly, “there is contrast between what The Hunger Games tells us about inequality and what it shows us.”[15] During the Games, Rue tells Katniss that the District 11 citizens are all forced to work on the farms for the harvest and are whipped for resisting or stealing the food. Katniss realizes that perhaps there are benefits to being the poorest district, since the Capitol ignores most of what goes on in District 12. What she has stumbled onto is white privilege: she may be poor, but her skin color gets here more freedom than Rue gets. This important detail, however, receives almost no attention in the book and is completely left out of the film.

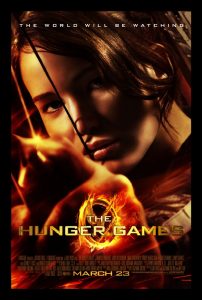

The film adaptations commit even more strongly to racial differences than the do the novels. In an interview, Collins said that she envisioned the world of the novels as having experienced ethnic mixing over hundreds of years, making the average person’s skin “olive” colored.[16] In writing a novel, she was inherently free from the burden of describing every member of a crowd, a burden that the film, on the other hand, must meet. And even though Collins helped to adapt the screenplay, the film uses white actors for nearly every scene outside of District 11. In a strong evocation of slavery, scenes of District 11 in Catching Fire shows black workers hunched over crops in the fields, under the gaze of Peacekeepers who patrol the area. Many viewers criticized the use of a white actress, Jennifer Lawrence, in the role of Katniss, a choice that ignored her “olive” complexion. Whitewashing—making nonwhite characters white with casting—is very common in the film industry as a supposed means to improve commercial success. As Sonya C. Brown writes, any attempt in the novel to lessen racial divisions is undone by a “casting call that deferred to an apparent preference for a white/Caucasian heroine in an era of racial and ethic division.”[17] This film adaptation, then, is a good metric of the prevailing racial attitudes in the country.

The casting of Rue also generated a strong backlash, but for the exact opposite reasons. Many readers apparently missed the part about Rue having dark skin and released a storm of profane, angry social media posts when they saw her played by an African-American actress in the trailer.[18] As one writer points out, these reactions indicate that certainly do not live in a post-racial society despite proclamations of such after the 2008 election.[19] But the reactions also indicate that Collins managed to convince her readers—or at least the less observant ones—of the fictional post-racial society she fabricated.

The film, however, is obviously confused about and conscious of its racial image. On the film poster, Katniss appears much darker in skin tone than the pale Lawrence who plays her, and the District 12 residents appear dark by contrast when seen alongside Capitol workers who are all either dressed in white or powdered to near-literal whiteness. In this sense, the people with whom we are meant to identify are victims of the phenomenon Dyer has observed in which whiteness is an unachievable perfection.[20] The Hunger Games, alas, demonstrates the messiness of cultural representations of race, delivering conflicting messages at various levels of analysis. And from the series, we learn the novels and films can hide racial messages, with the effect that, through our emotional investment, we fantasize about a world we don’t actually want.

[1] Before Harry Potter.

[2] Imran Siddiquee, “The Topics Dystopian Films Won’t Touch,” The Atlantic, November 19, 2014, accessed December 12, 2017.

[3] Alissa Wilkinson, “Why ‘The Hunger Games’ Is About Racism,” Christianity Today, November 24, 2014, accessed December 12, 2017.

[4] She was also watching reality TV, which, combined with the war coverage, created the Survivor-esque nature of the Games. That these two elements fused so easily is perhaps a cause for concern.

[5] “Team ‘Hunger Games’ talks: Author Suzanne Collins and director Gary Ross on their allegiance to each other, and their actors,” interview by Karen Valby, Entertainment Weekly, April 7, 2011.

[6] Reinforcing the narrative of the relative levels of poverty and freedom is the numbering system of the districts. In a novel meant for younger readers, hearing that District 1 is the wealthiest and that 12 is the last number since District 13 was wiped out creates a straightforward ranking.

[7] Siddiquee, “The Topics Dystopian Films Won’t Touch,”

[8] The Peacekeepers are the agents of oppression and order for the Capitol. The name may indeed be a jab at the UN.

[9] But, as I will later examine, racial issues linger but are kept away from the plot and more importantly, critical commentary.

[10] Suzanne Collins, The Hunger Games (New York: Scholastic, 2008), 45.

[11] Mary C. Burke and Maura Kelly, “The Visibility and Invisibility of Class, Race, Gender, and Sexuality in The Hunger Games,” in Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Post-Apocalyptic TV and Film (New York: Palgrave Macmillan), 60.

[12] Touré F. Reed, “Why Liberals Separate Race from Class,” Jacobin, August 22, 2015, accessed December 12, 2017.

[13] In the novel, these events in District 11, obviously beyond Katniss’s knowledge at the time, are only vaguely hinted at once she leaves the Games. The film then, which otherwise stays very true to the novel, takes some liberties in showing this conflict.

[14] Richard Dyer, “The Matter of Whiteness,” in White: Essays on Race and Culture (New York: Routledge, 1997).

[15] Burke and Kelly, “Class, Race, Gender, and Sexuality in The Hunger Games.”

[16] “Team ‘Hunger Games’ talks,” interview by Karen Valby.

[17] Sonya C. Brown, “The Hunger Games, Race and Social Class in Obama’s America,” in Movies in the Age of Obama: The Era of Post-Racial and Neo-racial Cinema (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield, 2015).

[18] The casting of Thresh, the other tribute from District 11, generated far less controversy, possibly because readers picked up on the stereotypical black descriptions— “giant” and “ox”—that Collins uses

[19] Ellen E. Moore and Catherine Coleman, “Starving for Diversity: Ideological Implications of Race Representations inThe Hunger Games,” The Journal of Popular Culture 48, no. 5 (October 19, 2015).

[20] Dyer, “The Matter of Whiteness.”