Joyce S. Tseng

Let’s face it: all movies are about gender. It is ubiquitous. Biologically, sure, there are only two categories of sex. But over time, gender has grown increasingly messy—increasingly transgressive. The simple issue of gender influences the reception of a movie more than we realize. Split-second assumptions are made about characters based on their gender all the time. We immediately assume the incompetence of Elle Woods in Legally Blonde to get into Harvard Law. And of course, power dynamics could not be established in the same way without the distinction between males and females. We aren’t as terrified of Harley Quinn as we are the Joker. Popular culture is embedded with gender scripts, reflective of evolved sexist stereotypes and attributions. However, there is a salient rise of gender fluidity in modern society—gender is much more confused than it historically has ever been. But what we see movies do with this reality is guide the colors back within the lines.

“Makeover movies” are a standard storyline of Hollywood films. I’m talking about the ones where the ugly, geeky girl is magically transformed into a sexy, chic woman. In these movies, the makeover highlights fashion as the driving tool—a stereotypically female-attributed matter. The movie’s message goes beyond the upgrade of a woman’s frumpy wardrobe though and proves the need for alterations in her personality and lifestyle too. These movies try to get at some sort of moral development of the woman, as a consequence of their makeover, tailoring them to fit the mold of the acceptable, ideal woman. Grease’s Sandy goes from a conservative prude to a leather-wearing fox—and this is praised.

If we turned our attention to feminine men, they have historically not done well in Hollywood movies, or at least, feminine men are never the protagonists. The disdained antagonist of Silence of the Lambs (1991) is a psychopathic transvestite. Dr. Frank N. Furter in The Rocky Horror Picture Show is depicted to be an alien transvestite, whose name is a clear spin-off of a classic gothic monster, but also alludes to a phallic symbol. Though male-makeovers are not as common, the idea of remasculinization is not new to Hollywood. The quintessential example is Clark Kent, a glasses-wearing newspaper reporter turned into a superhero hunk with perfectly gelled hair. Each makeover renders the image of the ideal, which has proven to be attractiveness-oriented and sexualized. Similar to the moral development of women, several movies have addressed the emotional, behavioral meaning of masculinity. Tyler Durden in Fight Club spends his days selling soap, but is provoked out of boredom to join an underground fight club. He uses fist fighting as a means of liberation, reverting him back to primal masculine functions. The film serves to show men what it means to be men. The popularity and prominence of makeover movies suggest that we, as consumers of film, desire to see people combat the threats to their archetypal form of gender. But, here is the problem. If we insist this demand and desire to be true, then we succumb to an inescapable, exclusively male point of view. Gender and cultural studies professor Brenda Weber asserts, “American masculinity has long been predicated on the values of the self-made man.” The male-makeover is autonomous and upholds individualism. However, in the case of women, the transformation is rarely self-made and actually works to serve men.

Let’s consider movies about women learning how to be women. Donald Petrie’s Miss Congeniality (2000) does just that. The uncomplicated premise of a female FBI field agent, Gracie Hart, who goes undercover as a contestant in the Miss USA beauty pageant sets the stage perfectly for the argument of guiding a woman to her idealized form. The specific casting of Sandra Bullock as Gracie asserts much about the character. Bullock’s charm is not one that fits the stereotypical symmetric, doe-eyed, blonde haired beauty; she brings an air of quirkiness and boyish athleticism with her presence, which becomes conspicuous in the scenes where is surrounded by the other beauty contestants. Gracie’s less than elegant mishaps and unfeminine mannerisms, like her pig-ish snorts when she laughs, pin her as a feminine outcast. Though her tomboyishness allows her to fit enough into the male dominated field of the bureau, it is clear she can never truly assimilate into the group because of her gender. She is notably asked by a stranger in a bar, upon learning of Gracie’s occupation, “Do all the women in the bureau really have to wear those masculine shoes?” Here and throughout the movie, Gracie’s occupation as an FBI agent is consistently reduced down to her body, etiquette, and fashion, forcing her back within the realms of femininity.

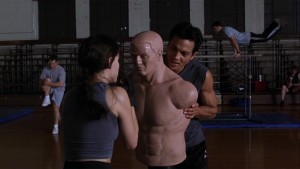

The irony of the plot lays in the notion that a woman can learn how to be a woman when taught by men. Gracie’s beauty pageant coach Victor Melling, played by Michael Caine, embodies the poise that Gracie does not. He “glides” when he walks, speaks with a posh British accent, and frequently sports immaculate suits with pink accents. He is the driving force of Gracie’s makeover: picking out the dresses she wears, teaching her how to walk gracefully, and introducing her to feminine products like plastic breast paddings. It is important to notice that Petrie intentionally decided for the pageant coach to be male, but more importantly for Victor Melling to be gay. He is essentially male, but not quite the archetype. He is the primary tool in the makeover but cannot be the ultimate goal of Gracie’s transformation—that is, she is not changing herself to woo Victor. But his function to the story makes it so that Gracie’s makeover cannot be “self-made.” The movie demands that Gracie is guided away from her boyishness and fulfill her female body as it ought to be, but makes a point to show that this package is a man-made construct.

We must realize that the plot of the movie conveniently makes it so that Gracie’s gender is the primary reason why she is chosen to go undercover when the Miss USA beauty pageant is targeted. The audience knows all along that Gracie is the one for the job, but it takes the male agents a session of computerized photoshopping of agents into a one-piece female swimsuit to realize the fact. The scene is comical, featuring a group of strong, grown men huddling around a computer, playing dress up. The agents cringe and laugh at different women of different shapes and ages as they are subject to their man-controlled game. The political implications here are clear. The men critique every inch that a woman aesthetically has to offer, and pass their judgment on what is acceptable or not. What is interesting is that Gracie also partakes in this activity. She plays along with the men, mocking the women on the screen, feeding into the fixation on the female body. When the agents finally settle on Gracie being the most believable option, Gracie’s amusement immediately shuts off and she tells the guys to cut it out. It is only when fellow agent Eric Matthews tells her, “Don’t kid yourself. No one thinks of you as a woman,” that she begins to take the mission seriously. So, here we have a woman, not wanting to be considered a woman because of the beauty pageant contestants carrying the implications of being unintelligent and materialistic.

However, it is easy to miss that Gracie’s transformation actually revolves around Agent Matthews. He coaxes her and encourages by saying, after a couple of “butt-shaping exercises”, she would fit right in at the contest. The absurdity of this scene is because it takes place in the training room, while Gracie is kickboxing—an intensive, strength-oriented workout. Here, Agent Matthews is advising an obviously physically fit woman to alter her workouts towards more aesthetic purposes and toning, as opposed to muscle building. It takes Agent Matthews’ comment that Gracie is not considered a woman for her to take the mission. Throughout the movie, he repeatedly pokes fun and ridicules Gracie during her efforts to become a believable pageant contestant, mocking her with doughnuts when she has to diet, sarcastically cooing at her when she is dolled-up. Yet—not surprisingly—by the end he falls in love with her and successfully asks her out on a date. To the audience, the movie makes clear that for women, turning yourself into something of a pageant girl will win you male recognition.

Thus, within the film narrative, the audience Gracie caters towards is men, namely Agent Matthews. But, Petrie also incorporates the literal audience of the movie and subjects them to a male perspective. Film theorist Laura Mulvey’s concept of “the male gaze” claims that no matter who you are as an audience member, because the camera is treated as if it were male, you have no choice but to view the movie as a male too. Let me explain. Mulvey suggests that a film camera stimulates the voyeuristic tendencies of the audience; we are awakened and find pleasure in viewing others, specifically in private domains from which we are usually concealed. In Miss Congeniality, Gracie is set up with several spy cameras when she goes undercover, thus unlocking the backstage, dressing room world of the beauty pageant to the male FBI agents. The men gather around the screens, and in one scene even bring popcorn, to view the women in bathrobes, hairnets, and swimsuits. The way these sequences are edited place us in the shoes of the men, watching the room from Gracie’s point of view, which is also the view the male agents have an in on. We as an audience are included as peeping Toms, encouraged by the agents ogling at the women on the screen.

Admittedly, makeover movies tend to fall under the category of “chick flicks,” implying that they target a predominantly female audience; but if we delve deeper and ask what these movies are encouraging women to take away from the narrative, it is chiefly male-centered. By watching these films, women are taught to desire a materialism-triggered moment of recognition and men are reaffirmed of their approval of the makeover. Gracie accepting the “Miss Congeniality” award and giving a speech about how grateful she was to have been a part of the pageant and from the mission, how she has changed as a person for the better is the way the film reconciles its plot and gender dilemma. The award and what it stands for literally celebrates Gracie’s ability to have adapted to suit her personality and behavior to the taste of others. We go from watching a kickboxing, self-assured woman turn into a tamer, peace loving appeaser—and we applaud this ending and call it a success.

Bibliography

Ferriss, Suzanne, and Young, Mallory, Chick Flicks: Contemporary Women at the Movies. London: Routledge, 2008.

Ford, Elizabeth A., and Mitchell, Deborah C., The Makeover in the Movies: Before and After in Hollywood Films, 1941-2002. North Carolina: McFarland, 2004.

Weber, Brenda R., “What Makes The Man? Television Makeovers, Made-Over Masculinity, and Male Body Image,” International Journal of Men’s Health 5.3 (2006).

This essay was written in the style of David Foster Wallace.

This essay was peer edited by Dew Maskati.