ALLEGORICAL COMPLEXITY #2 — Attack the Block

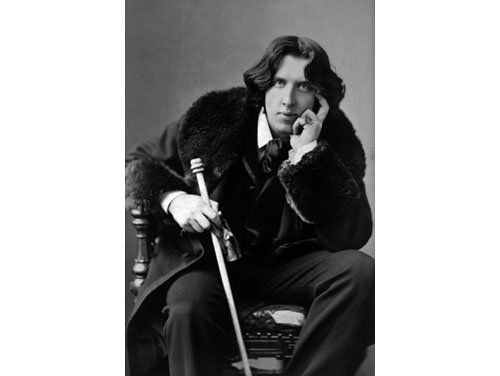

A new problem: What are we to say about stories that feature both allegorical and literal versions of the same thing, of the same class of object or type of person—about True Blood, for instance, whose vampires code comprehensively as queer even though the show also includes among its characters several mortal, day-walking gays and lesbians? This is a real problem, because the show seems to be drawing a distinction, prompting a rigorous reader, one perhaps suspicious of allegory, to insist that the vampires can’t possibly be in some general way stand-ins for queer folk because the show already possesses these latter, and they are not coterminous with the vampires. Placing an allegorical construct in the same room as its literal equivalent doesn’t, as one might suspect, make the allegory stronger or easier to explicate. Quite the contrary: The allegory and the literal referent are going to be locked in a struggle for the relevant name or meaning, and it’s not entirely clear which is going to have the upper hand in that fight. You might think that the literal term has home turf advantage. If a gay person and a vampire are standing next to each other, and I only get to call one of them “gay person,” I’m going to choose the gay person. That’s what it means to say that the presence of the literal term can prevent the allegory from coalescing, like the trace amounts of yolk that ruin your every attempt at meringue. But then hyperbole is at the heart of allegory—you create an allegorical version of x by exaggerating certain features of x—and in that case, the non-literal construct can easily seem like the better version of the thing, more fully and vividly itself, purer, pushed further away from the imaginary average against which all specific difference is gauged. If Dracula and Oscar Wilde double each other, I might decide that it is the vampire who is really queer, whereupon gay and lesbian people will find themselves outflanked, normal by comparison, conceptually maneuvered bank into the ranks of dull humanity. The allegory can poach from the literal term its very name.

If we’re going to make sense of this particular deviant variety of allegory, it will help to have the terms provided by an unreformed structuralism, whose core insight was that all stories begin by generating some opposition or another: A and B, cowboy and Indian. The idea, then, is that since most of us experience oppositions as cockeyed and agitating, the business of nearly any story will be to stabilize its antithesis, though there are different ways a movie or novel or folktale might do this: by subordinating one term to another and perhaps by eliminating it altogether (cowboy defeats, expels, or guns down Indian); or, alternately, by fusing the two together into some unforeseen third (cowboy marries Indian). Storytelling can become more complicated, of course, as it begins shading in intermediate steps that already contravene the central opposition (the half-breed, say, or the white Indian) or as it appends secondary oppositions to its core one: (cowboy and East Coast railroad interest). But nearly all storytelling is at heart a play with oppositions, and the trick when considering a complicated story is to discern the master antithesis (or small set of antitheses) that underpins its many more local conflicts. The remarkable thing, then, about stories that contain allegorical and literal versions of the same thing is that they sabotage this most basic feature of narrative; they monkeywrench the binary by plugging the same term into each of the opposition’s slots—once nakedly and then again in disguise—and thereby create reflexive stories that are not, however, immediately recognizable as such: cowboy and cowboy, teasingly and with the air of paradox.

That such stories pose special challenges should be clear from Spielberg’s War of the Worlds, released in 2005. Nearly every newspaper and magazine reviewer—and, I suspect, most ordinary fans—thought that the movie was about terrorism or that it was 9/11’s conversion into science fiction: It was “the first serious post-9/11 sci-fi movie,” “a 9/11 allegory,” a reminder that “terrorists can take out a big chunk of the Manhattan skyline,” a surprisingly solemn tour of the nation’s “worst terrorism nightmares.” The New York press took to warning its readers off the movie: “merciless,” they called it, and “shocking”—35mm PTSD. And it is certainly true, as the reviewers all mentioned, that the film is crammed with “allusions” and “parallels” and “references” to 9/11: civil emergency in greater New York, panicked urbanites sprinting down city blocks, overwhelmed beat cops, airplane wreckage, a wall of the missing, and—least generically, most jarringly—a rain of ash.

That War of the Worlds is not about terrorism one knows all the same, because it tells you as much, and in so many words—except, of course, one doesn’t know it; everybody missed it. The movie’s hero has two children, and as they escape from the attack, the younger one screams: “Is it the terrorists?”—and gets no answer. Then a minute or two later the older one repeats the question, more calmly this time: “What is it? The terrorists?” “No,” the father says, “this came from someplace else.” All the more remarkably, the film has already by this point identified that Someplace Else or Other Thing, the thing that isn’t terrorism. Some four minutes into the movie, Tom Cruise’s ex-wife instructs him to stay on top of their teenaged son over the weekend, because he has a research report due “on the French occupation of Algeria.” And there it is: The malicious gag underlying the movie is that the invading Martians give a high-school student all the material he needs to write a really bang-up paper about occupation or that they turn his assignment into a family project: This is the weekend everyone learns about empire.

War of the Worlds was thus a thought experiment or indeed a political education—one specific to the middle years of the Bush era: Can you imagine a force powerful enough to do to the US what the US has done to Iraq? Can you imagine, via analogy and extrapolation, a military wielding technological superiority over the US of a kind that the US currently wields over the world’s other nations? Or as one character says of the invaders: “They defeated the greatest power in the world in a matter of a couple of days. … This isn’t a war any more than there is a war between men and maggots.” What the reviewers inexplicably overlooked was that terrorists do not occupy entire countries. And that’s all you need to bear in mind to realize that Spielberg’s movie was is no sense an homage to 9/11—just the reverse—it was a deliberate and principled insult to the instant sanctity of that day, a way of putting 9/11 back into perspective by staging on the same terrain an event of incomparably greater magnitude, a way, that is, of showing the New Yorkers who were told to skip the movie just how much worse it could have been: Baghdad.

This is the sort of thing that becomes possible when allegory doubles its referent; such doubling is, indeed, one of the only ways that narrative can place the same term on both sides of an opposition; X fights X; the US invades the US; Americans as colonizers, Americans as colonized. This is the structure we’ll need to carry forward with us if we want to make sense now of Attack the Block, which is Super 8’s English twin, the other alien-invasion movie from 2011 that pulls in equal measure from ET and the Goonies: more adventuring tweens, more BMXs, more aliens that seem visible only to the pubescent. But then Attack the Block is also the first movie I’ve named that is openly about race in some entirely literal and earthbound sense. This is first of all a simple matter of casting: Almost none of the movie’s heroes are conventionally, ethnically English; all but one come from African or Caribbean immigrant families. If you haven’t seen the movie, it’s not enough to imagine The Goonies with English accents. You have rather to imagine The Goonies as new-model Cockneys, black and mixed-race and speaking grime patois. But then it’s not just the characters: Attack the Block is also telling a story about race; indeed, it is telling perhaps the most familiar racial story of the last few generations, the one about integration and enfranchisement. All you need to know is the bare outlines of the plot: Once they start fighting the movie’s aliens—and fight they do, to the death; the movie’s resemblance to ET and Super 8 ends there—the boys are transformed from the piece’s villains to its heroes. They begin the movie by mugging a young white nurse, but they end it by saving the day. In other words, it’s not just that Attack the Block is one of the most extensive pieces of black British pop culture yet produced, and in that sense some kind of landmark. The movie is actually walking you through a reassessment of black Britain and can, to this extent, easily seem like an advance on that recent crop of movies that make the English poor seem like the worst people on earth, though it has to be said that those films’ chosen technique for communicating their sour insight is simply to remake Hollywood movies on English soil: Harry Brown, for instance, which casts Michael Caine as an East End vigilante and aitchless Eastwood—it’s there in the title, if you squint: “brown” = “smudged” or “unclean” = Harry Dirty; and especially the remarkable Eden Lake, which is Deliverance transplanted to a not-so-rural Buckinghamshire, with hoodie-wearing poor kids in the place of Georgia hillbillies: 13-year-old proletarians carving up their betters. These movies and others like them leave the impression that the British working class has simply gone feral—the impression, that is, that class relations in the UK have by this point simply snapped or that basic modes of sociability or decency or respect have disappeared, with dehumanized workers and lumpens stuck living in perpetuity on the far side of their old traditions. To a considerable extent, then, Attack the Block asks to be read as a polemical response to this cinema of broken Britain. The movie begins in the mode of Harry Brown and then simply demands that viewers revise their judgments. The respectable white audience’s designated proxy obtrusively changes her mind. At the beginning of the movie she and an older white neighbor commiserate: “They’re fucking monsters.” But by the end of the movie, she is telling the cops to back off from the bruvs: “I know them. They’re my neighbors.”

One way to summarize Attack the Block, then, would be to say that it is a story of uplift and interracial friendship, in which Britain redefines itself in order to make room for its newest members. Nor is it overreaching to mention Britain in this context; the film has the nation unmistakably on its mind. It is set on Guy Fawkes Day, for one, and so asks to be read as a redo of 1605—England’s second saving!—with West Indian yardies performing the patriotic gallantries once reserved for Protestant knights. More to the point, the movie’s 15-year-old hero, propelled in one scene from out a high window, saves himself by un-metaphorically clinging to the Her Majesty’s flag.

The movie, in sum, revises British nationalism by pushing it in a liberal and multiethnic direction, though we will want to note that this observation is dogged by two persistent instabilities.

First: The film’s visuals might be plenty nationalist—all fireworks and Union Jacks—but its dialogue is not. Anything but: The film’s teenagers routinely say that they are fighting only to defend their housing project, their block. Where the movie is John-Bullish, the characters are instead intensely localist: “We wouldn’t have mugged you if we’d known you lived here.” That’s a sentiment available only to someone whose sense of the imagined community stops cold at the corner shop. And to this jingoism of the neighborhood the characters add a working-class or black ethos of self-policing—the code, in the US context, of Stop snitching and jury negation and Walter Moseley novels: “This is the block. We take care of things our own way.” It might be possible, when trying to make sense of the movie, to simply superimpose these two terms—the nation and the locality—in which case we would conclude that Attack the Block is proposing a council-estate nationalism, a black-white alliance of the distrustful and cop-hating poor. There’s something to this idea, and yet the individual components remain visible and not fully resolved into one another.

Second: The movie does almost nothing to revise one’s perception that its heroes are sadistic predators. It merely concludes that sadistic predators are sometimes useful to have around. The film’s few white men are by contrast all emasculated. “I am registered disabled” one of them says; “I’m a member of fucking Amnesty!” shouts another; and the movie’s gibe is that these amount to the same thing, just two different routes to castration, physical and ideological—twin softnesses. This will obviously complicate our sense of the movie as liberal, since even as the movie is promoting a kind of racial liberalization, it is deciding that liberal men aren’t good for much, and the burden of British masculinity will thereby pass over to the nation’s young Trinidadians and Congolese, fourteen-year olds with knives and swords and bats and explosives, a nine-year old with a handgun, announcing that his new warrior name is “Mayhem.” Attack the Block sometimes gives the impression that it is recruiting the child soldiers of South London.

But then those two instabilities are nothing, mere tremors, compared to the movie’s central and defining instability, the oscillation around which it is constructed. I’ve been describing the role of race in the movie at the literal level, but then there is also an allegorical level, in which everything I’ve just described is taken back. This makes for a vast and, I think, unsolvable puzzle, though in many ways Attack the Block’s racial allegory is unusually bald and not in the least puzzling and amounts to this: The aliens are also black—hairy, subhuman, grinning, and black. I don’t actually want to put too much emphasis on the color in isolation. Racial allegory, after all, is not automatic. Lots of black things are not black. Darth Vader is not black. If all we had to go on is that the creatures are inky-dark, I’d say we could let it slide. But that’s not it: The movie is entirely upfront about how it wants us to understand the aliens’ ebony. The kids stand over the first adult monster they kill, and two of them speak out loud what they see: “Wow, that’s black, that’s too black to see. … That’s the blackest black ever, fam. … That’s blacker than my cousin Femi”—which moniker is Nigerian and usually followed by names like Ogumbanjo and Kuti.

The movie, in other words, openly places the creatures on a spectrum of African-ness. What’s more, it has various ways of expanding on this tactic. Only once does Attack the Block’s dialogue turn openly nationalist, when a gang member sticks up for the home country at the expense of Africa, pouring contempt on a white philanthropist off doing aid work in Ghana: “Why can’t he help the children of Britain? Not exotic enough, is it?” Or there’s this: One teenager warns another than an alien is about to attack by shouting “Gorilla!”—and then that’s another clue. Attack the Block is, at the level of its allegory, an inversion of Rise of the Planet of the Apes, a second film about berserking primates, and with the meanings from that other movie largely intact—the meanings, not the judgments. If Rise stages a latter-day slave rebellion—an insurgency against the mass incarceration of black men, an uprising that is at once prison break and revolution—then Attack the Block stages a related event, a bit of colonial turnabout, but asks us instead to cheer its suppression. Anyone who goes into this movie hoping that the Jamaican newcomers are going to battle the white dragon of the West Saxons or cut down the English aristocracy’s heraldic wyverns is going to have to swallow hard. For Attack the Block offers to enfranchise black Britons only by giving them creatures to kill who are blacker than themselves. A group of mostly black teenagers earns its citizenship by systematically cutting down the new crop of even darker arrivals. Conceptually, this is rather astounding: The film is telling two antithetical stories at once—and not via a multiplot—there is no main plot and contrapuntal subplot; it is telling two contradictory stories, but it only has one plot; the same story, then, but susceptible to two radically opposed constructions: a parable about learning to like black immigrants that is at the same time a fantasy about wiping them out—“Kill ‘em! Kill all them things!” The creatures in Attack the Block are so very jet that they often blur into the shadows, but the filmmakers, in what must have seem like an inspired touch, have given them glow-in-the-dark fangs, which means you can only see them when they bare their teeth. There’s an ugly old joke in the American South — something about hunting at night — to which this image is the reinvented punchline.