Three Theses on Fright Night

•THESIS #1: It’s harder than you might think to script a straight vampire.

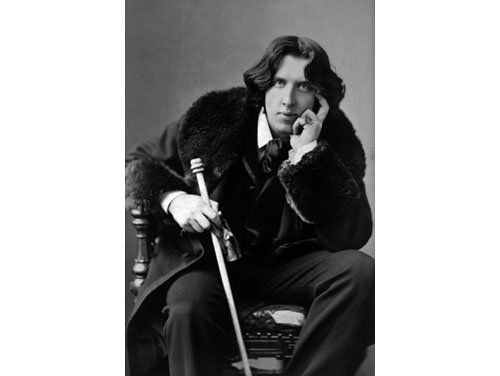

I don’t normally go in for literary biography, but here’s one case where it can actually help us refine an argument. Some background: Bram Stoker grew up in the same circles as Oscar Wilde, on the fancy side of Dublin, and the two were roughly the same age, close enough at least to evidence an affinity. One year, after Wilde left to go study in England, his parents invited Stoker to spend Christmas Day with them, as though he were a substitute son—as though, that is, Stoker were a plausible stand-in for Wilde. And the Wildes clearly weren’t the only ones who thought this: Stoker went on to marry a woman, a legendary local beauty, whom Wilde had already courted. That Stoker’s most famous novel is by any ordinary measure anti-queer—the sexually peculiar characters are hunted down and killed; it doesn’t get much more anti-queer than that—would seem to give us the key to interpreting the relationship between these men. We would want to say that they were rivals, and this in some sharp and antithetical key: the queer and anti-queer alternatives in the same Anglo-Irish scene, though if that’s the case, then it becomes harder to see how they could so effectively pinch-hit for one another. Here, at any rate, is Oscar Wilde, looking like one of Virginia Woolf’s sisters…

…and here is Bram Stoker, whom one could easily mistake for Ulysses S. Grant.

The eye, in other words, tells us that these were very different men. One begins to suspect that the Dracula story was locked in a death struggle with Oscar Wilde; that the original novel already had its own vexed relationship with male celebrity; and that its plot is at some level an unedifying fantasy about people like Stoker eliminating people like Wilde. But then what do we do with the information that the grown-up Stoker was obsessed with Walt Whitman, writing the poet long letters in which he described himself as a “strong healthy man with a woman’s eyes and a child’s wishes,” confessing to Whitman his longing for a man who could play wife to his soul? Or that the adult Stoker eventually found such a man, a special friend and soul-wife, the alliance with whom was, he said, “as close, as lasting as can be between two men”? Or that he quit his day job to take a position in the London theater, in order to be near this companion, who was an actor? In the wake of those questions, a rather different rendering of Dracula becomes available—not that vampire stories are homicidal fantasies about eradicating queer people, but that it is in vampire stories that queer people begin working out their complicated feelings about their own outlandishness.

I’ve already said that vampire movies are an ongoing meditation on Nietzsche; if I say now that they have been, from the very start, an open-ended reflection on queerness, then that’s almost the same thing anyway. In the 1931 Dracula, the vampire takes as his minion a trim, flustered Englishman who spends much of the movie gazing longingly at the Count; he describes how the handsome foreigner “came and stood below my window in the moonlight,” as though carrying a lute or a dubbed copy of “In Your Eyes”; he goes to pieces when he finds his master carrying a woman matrimonially down a long flight of stairs. Around 1970, there was a bubble of lesbian vampire movies, of which a Belgian joint called Daughters of Darkness, from 1971, is easily the best. Tony Scott’s The Hunger, from 1983, is in this sense a rather belated contribution to the form, and True Blood, which is probably the most extravagant, extended queer allegory that pop culture has ever produced, in which the male vampires gloss as gay even when they’re dating women, achieves its effects only by compiling and concentrating in a single arena eight decades’ worth of camp and code and capes: “God hates fangs.”

So ask yourself again: Could you, even if you wanted to, make a vampire straight? The question is worth lingering over, because Fright Night is an easy movie to underestimate, and that question names the funny little task it has set itself. For Fright Night has, indeed, figured out a way to (mostly) straighten its Dracula figure; it has sent the vampire movie into conversion therapy. The movie devises at least three techniques to this end:

i. It makes the vampire killers queer in place of the vampire. Or if not outright queer, then at least scrawny and boyish and sissified. We’ll want to bear in mind: The movie is remarkably faithful to the Dracula plot, which it self-consciously restages in suburban Los Angeles. A teenaged boy works out that a vampire has moved into the creepy house next door, and he spends the length of the movie recruiting a gang of hunters to help him chase the demon back to its lair, overcoming the skepticism of potential allies, parrying Belial’s preemptive attacks, &c. It’s the devil-tracking posse that most pointedly recalls Dracula, though with a difference. Stoker’s band of brothers were, of course, all kinds of sturdy and sea-captain-ish, but the movie has assembled a team of milksops and pencildicks in their stead. Fright Night’s opening scene shows its main character failing to get his girlfriend into bed—or worse. He eventually does get the girl into bed and then loses interest. First: “Charlie, I said stop it!” Then: “Charlie, I’m ready. … Charlie? … Charlie???” The very first thing the movie wants us to know about its protagonist is that his sexuality is unsteady. That point is then reinforced by two other characters: first, by his best friend—short, twerpish, with a tweedly, still-breaking voice and the shrieking laugh of a girl on a playground; and then by the group’s eldest member and nominal leader: The film’s affectionate joke is that its Van Helsing figure, sought out by our young protagonist, is an aging English actor who used to play a vampire hunter in bad horror movies. Fright Night thus has a certain null value in its central position—not a hero, just a man paid to mime heroism; not a man of action, just an actor—and the movie effortlessly compounds that idea by making the actor a coward to boot. More interesting: The character is clearly modeled on Peter Cushing, who played Van Helsing in the Hammer Dracula series and whose first name Fright Night has lovingly borrowed—Peter Vincent. And yet here Cushing’s place is taken by Roddy McDowell, who is a different actor altogether, entirely devoid of the former’s sonorous and hatchet-faced English machismo. Cushing played Van Helsing the same way he played all his roles, as an ill-tempered headmaster, wielding a wooden stake the way one might a pandybat or a birch switch. But McDowell, from his very first appearance, projects shades of the old queen, dandified and elfin, and he sounds like no-one so much as Winnie the Pooh. The movie thus manages to attribute a functioning heterosexuality to its vampire simply by rejigging the other end of the antithesis. The Dracula figure is a seducer and loverboy, but then that’s almost always been true in vampire movies—nothing remarkable there—and nothing about that role has ever prevented a vampire from functioning as queer. The position, indeed, usually spills over with excess and omnisexual energies. Strictly speaking, this is true even of Fright Night. The vampire lives with another man; we watch him intergenerationally recruit at least one teenaged boy over to his way of life. It’s just that the obtrusively fractured masculinity of the vampire’s enemies will tend, in this one case, to muffle our perception of the monster as queer. None of the men in this movie are typical guys. The vampire, unusually, comes closest.

ii. It borrows from werewolf movies. It’s tempting to put this point in technological terms: The movie was produced in the golden age of the bladder effect, in the aftermath of The Howling and Wolfen and An American Werewolf in London, all of which came out in 1981, the Year the Moon Never Waned, and Fright Night cannot resist the temptation to wrap its actors in hairy, bubbling latex, delivering not just one, but two distinct transformation scenes—werewolf scenes in a movie that isn’t about werewolves. One recently bit human simply metamorphizes into a wolf, and even the Dracula figure, when preparing to feast, turns demonic and feral and at least demi-lupine.

I don’t need to tell you: More recent movies typically conceive of vampires and werewolves as sworn enemies. What’s distinctive about Fright Night, then, is that it completely collapses them together, and this involves rather more than special effects. Werewolves, after all, are the butchest of the canonical movie monsters; they put on display a beserking, hungry, animal male sexuality, brawny and comprehensively bearded. Fright Night is, in effect, trying to borrow the werewolves’ unbridled heterosexuality and re-assign it to the vampires.

iii. It borrows from ‘80s teen sex comedies. Fright Night’s teenaged hero stands at a window watching through binoculars as a bra unclasps. The camera pans over his cluttered bedroom, disclosing a Playboy casually spread across the floor. He is made to speak lines like: “Jesus, Amy, we’ve been going together for a year, and all I ever hear is ‘Stop it!’” The movie lets its viewers briefly think that it’s going to be another Losin’ It or Last American Virgin and then maliciously mutates into a horror movie instead. But then there was always something malicious about teen sex comedies, which were routinely marketed as raunchy and semi-pornographic, but were, in fact, the opposite of porn, precisely so: movies about people not having sex. The shared plot of all these film is that some men want to have sex but can’t, and if you’re going to find such a story diverting, you will have to be able to sign onto a certain understanding of sex: that it’s really hard to get laid—or, more precisely, that some versions of male sexuality are so stunted and hapless as to be a kind of acquired infertility. Sex eludes us. The point is clearer still in the throwback movies that have been made since the ‘80s, like American Pie and Superbad, since in those later films, the women are even willing—eager and squirmy—no longer the self-chaperoning matronettes of the Reagan-era—and the boys still can’t hack it. It will matter, of course, that we’re talking about a particular kind of boy: American Pie wants you to stand up and sing the Hallelujah chorus every time a middle-class white guy manages to maintain his erection.

This matters. If you work out the ways in which Fright Night is and isn’t like Spring Break or Private Resort, you should be able to specify what’s at issue with this particular vampire, what it is that makes this one monster so terrifying—his own singular brand of menace. At the beginning of the movie, our teen hero gawks shyly as a hooker in a mini-dress pulls up in front of his new neighbor’s house—that’s another one of those scenes pilfered from sex comedies—something out of Risky Business or The Girl Next Door. But then the neighbor moves in on the hero’s tenth-grade girlfriend, who has already sized up this new arrival and said: “God, he’s neat.” And worse, his mother, with the keen stammer of an aging lonelyheart, has already said the same thing: “It’s so nice to finally have somebody interesting move into the neighborhood.” Fright Night, in other words, turns the neighbor into the hero’s sexual competitor, and this to an almost ludicrous degree. Your typical teen sex comedy doesn’t feature any enemies; the pipsqueaks just keep getting in their own way. But Fright Night is, as it were, a teen sex comedy with a vampire-werewolf in the middle, which means that it has furnished the virgin with a nemesis, someone he can blame for his sexual impasse. Such is the movie’s particular construction of the vampire, the reason its gives you to beware the fiend: Vampires are to be feared because they hog all the women. The film hijacks the fear that has typically been directed against queer people and directs instead at a certain exorbitant straightness, a heterosexuality so consuming that it has become indistinguishable from its opposite. Fright Night is the movie in which the stud gets f*g-bashed, and how you feel about this is going to depend entirely on your tolerance for turnabout. Dracula, we need to keep in mind, is the guy who will bang your mother and then steal your girlfriend.

THE MATERIAL ON STOKER AND WILDE I OWE TO DAVID SKAL’S HOLLYWOOD GOTHIC.