PART ONE IS HERE.

Let’s grapple with this squarely. To begin by saying that Cowper wrote a georgic is to emphasize that the poem takes as its starting point conventions that have been laid down in advance—set procedures or narrative habits that will shape how it is able to make sense of the war. Looking hard at Cowper, then, and setting the poem alongside the accounts of the American Revolution that historians typically produce, should help us understand what kind of devices poetry possesses to bring into view planetary systems or world histories—devices, I mean, that prose fiction mostly lacks; and it also should enable us to say that current attempts by scholars to retell the Revolution as something other than a Myth of National Origins and to plumb instead the continental, hemispheric, Atlantic or global dimensions of the Event are not entirely anachronistic. The cultural historians argue that the late eighteenth century produced a nationalist turn within poetry and fiction—that it did much to fashion our now commonplace notion of national literatures, or our notion, indeed, that nations have literatures (e.g., Trumpener 1997, Kramnick 1999, Hawes 2005)—but the techniques of eighteenth-century poetry are largely out of keeping with this observation, and not the innovative techniques, but precisely the dowdy orthodoxies, whose frameworks are rarely “English” or “French” or “Spanish.” There are reasons to read poetry even if fine language does not make you sigh. If, you scan the long poems of the 1780s, you might be able to say how it is that even contemporaries conceived of the American Revolution as something other than American.

The other point to be made in advance about The Task is that there is a standard line about the poem and that this line is demonstrably wrong. The poem, again, is about a man hiking, thinking a lot about his life, about how much he loves nature, about God. This characterization immediately poses a problem, which is that none of this sounds all that global. If you look at old-fashioned literary history, it will credit Cowper with a few different innovations (Sitter 1982, King 1986). First, it will credit him with introducing into English poetry precise landscape descriptions of a minutely particularized place; then it will applaud him for his new emphasis on interior states, on the poet’s self or mind. The usual line about the poem, in other words, is that it begins someplace entirely bounded—a minor market town which to this day boasts barely six thousand people and is famous mostly for its annual pancake race—and then strikes out for someplace even more bounded, which is the brain’s concavity. The Task, this is all to say, is typically read as a document of withdrawal, enacting a pious man’s retreat from history—into the hills and into his head. Shame about the empire, but I was just headed out for a walk. It has been the tendency of critics to read The Task as the first real verse autobiography, a distended lyric, the prelude to The Prelude. Underpinning this interpretation is the simple fact that Cowper was, in fact, mad: a by all accounts decent man who was given to hallucinations and regular suicide bids; a never-marrying moralist who either was a hermaphrodite or took himself to be one; a curious mirror-world Calvinist who was entirely convinced by the doctrine of predestination and equally sure that he hadn’t made the cut—that God had ordained for all time that quiet, inoffensive William Cowper should suffer and die and then suffer on.[i] For many readers, the peculiar appeal of Cowper’s writing has been the opportunity to watch psychosis flare up from within the sedate regularities of neoclassical verse, and so to sense that aesthetic straining against its limit or facing its negation from within.[ii]

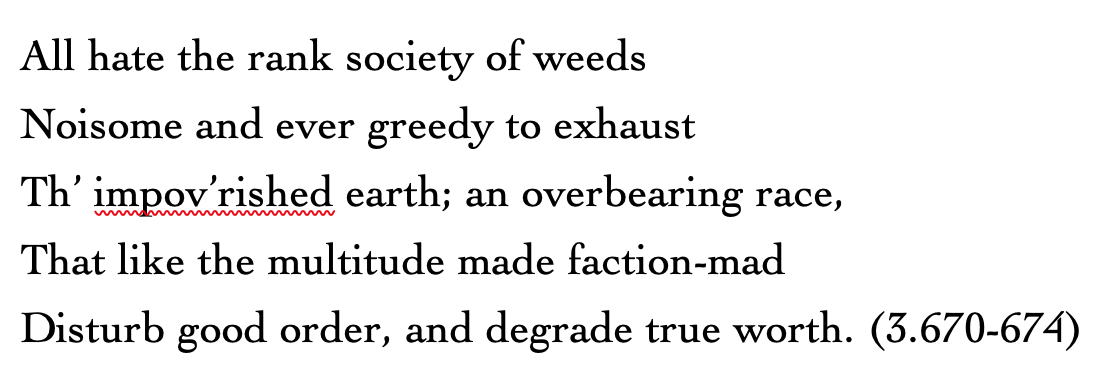

But to read Cowper’s poetry only as psychodrama is very much to miss the point. Against the tendencies of modern readers to celebrate The Task as a basically private utterance, or to slink into it like some kind of lyric hidey-hole, our errand is to insist on this long poem’s public and political valences, most of which are dictated by its form anyway, since the georgic is a species of countryside poetry, and it will always take a certain dumb ingenuity to look upon a historical landscape or agrarian economy and see only personhood, contorting these Big Objects so that they yield nothing but Subject. One of the oldest distinctions in poetic form—and it’s helpful as far as it goes—is between the georgic and the pastoral, where the first emphasizes rural work, a poetry of hoeing and weeding and threshing, and the second emphasizes rural leisure, a poetry of singing songs under shade trees while your friends eat pears they didn’t have to pick, on the understanding now that the other variants of rustic poetry, the country house poem, say, or the topographical poem, themselves come in relatively more pastoral or relatively more georgic forms depending on whether or not they draw attention to the working of the land. Mostly they don’t.

The georgic, in short, is farm poetry, verse that tends to describe Britain as a bustling nation of peasants and planters. It is also a form that we have lost the ability to read well, not least because it is entirely at odds with our own basically aestheticist and Heideggerian notions of poetic language. Dubbing itself “didactic verse,” the georgic has no interest in rejuvenating language by freeing it from its commonplace functions and petrified meanings. Poems like The Task make a big show of being useful to their readers, instructing them—or pretending to instruct them—on how to prune a diseased cherry tree or drain a soggy meadow. They are to this extent perfectly content to instrumentalize the world rather than lyrically disclose it. Even wastelands—this is Virgil—“Yield each a special product—pine wood that’s used in shipyards, / Cedar and cypress wood that go to the building of houses. … Willows provide our withes, elms leaf-fodder for cattle, / But myrtle bears tough spear-shafts, cornel your cavalry lances” (Virgil 1940: 2-442-443, 446-447). Set a georgic poet loose in a field full of daffodils, and he will figure out how to burn them for fuel. What is all the odder about the form, then, is that it isn’t actually useful; it is merely miming utility, weaving in enough sensible information, pilfered from actual farm manuals, to jostle readers from their arcadian reveries or spots of time, but never going into enough detail to amount to a genuine pedagogy. No-one ever discovered corn blight in his fields and marched back to the main house to consult James Thomson. Read alongside Hölderlin, georgics are going to sound pedestrian and scythe-minded: The poet watches a farmer hay his cattle or spots cold chickens huddling on a January morning. But read alongside, say, a poultry management guide, such verse will again seem fully poetic, interested less in communicating plain and practical facts then in linguistically embroidering such data and thereby generating a dense set of associations around farm work. A georgic poem will tell you a little something about how to rotate your crops, but it will drape its instructions in figurative language and thereby activate poetry’s full range of literary, mythic, and historical allusion, and this so as to transform agriculture into a libidinal-ideological object for readers who may or may not own farms. A georgic poem will make farming yield meanings that a seed catalog would not insist upon.

Cowper’s meanings will become clearer if you have a sense of what it is actually like to read this poem. Another thing that Cowper often gets credit for is the creation of a distinctive and personal-seeming lyric voice, an almost conversational intimacy, but to my ear The Tasks reads like a patchwork of older poetic styles and political idioms. Cowper was theologically a revivalist; he wanted to go back to what he saw as seventeenth-century forms of piety. And what’s true of his Protestantism is also true of his poetics: Long sections of the poem sound like Renaissance devotional poetry, like Donne or even more like Herbert. Sometimes he shifts over to the insolent republicanism of an Algernon Sidney. He does a pretty good Milton impression. And whole half-books read like the Tory satire of the early eighteenth century. The poem, I’m trying to say, can almost sound like automatic writing or the chatter of dead voices—a hundred years’ worth of English poetry, from maybe 1620 to 1720, conjured back to life in order to pass judgment on the 1780s. And I do mean pass judgment, because that combination of devotional poetry, republicanism, and satire yields pretty much what you would expect it to: the familiar sense that a once free and Christian England has been ruined by commerce and luxury. And Cowper, again, isn’t doing anything all that unusual on this front. If you go back and read Virgil’s Georgics, you’ll see that they already ask us to think about farming as a path to national rejuvenation. The barren world can be remade. And this is one of the ways in which the georgic was least like the pastoral: The arcadian vision of the latter tended to motivate a decline narrative, a world that had fallen away from some golden age of bounty and ease. The georgic, by contrast, was often at the center of a progress narrative, a historical vision of redemption through work.

So that’s a first important point right there: Countryside poetry is by definition a meditation on some social order and will have trouble sustaining meanings that are essentially private or personal or psychologized. And yet that point will only get us so far, since whatever sociality a market town and its outlying villages produce is going to be a sociality in miniature. The problem here is one of scale and scope. It is tempting to think that the georgic goes in for a minute localism; and this localism, despite older claims to the contrary, was decidedly not Cowper’s innovation. John Philips, in 1708, wrote 1400 lines on the West Midlands; John Grainger, in 1764, managed twice that on the sixty-eight square miles of St. Kitts (Philips 1708, Grainger 2000). This emphasis on the specificities of place proceeds directly from the genre’s agrarianist ethos: Farmers can improve or lightly modify their terrain, but they cannot fight it outright—or at least do so at their peril. No-one plants defiantly. Landforms, in other words, can only be standardized to a certain degree, at least in any historical period lacking bulldozers and explosives, and climates can be standardized almost not at all, which means that any farmer is going to have to develop a keen sense of geographical singularity, and it is this ethos—this close attention to the land’s shifting minutiae—that the georgic often seems to communicate. Each plot has its “peculiar cultivation and character” and will require “different crops” for “different parts”; “this ground with Bacchus, that with Ceres suits” (1.50-53).[iii] Formulations such as these put the georgic peculiarly out of step with the universalizing and regularizing tendencies we expect to find in neoclassical poems: the tick-tock of heroic meter, the endless recycling of a given writer’s pet rhymes, couplets compressing the poet’s every thought into the same ten-beat length, as though the language had ditched all sentence structures but one, every local observation ginned up into aphorism and abstraction. The georgic, simply by pointing out that you can’t grow pomegranates in Denmark, would seem to safeguard some sense of the world’s polymorphism against this poetry’s rote Latinity. Even Virgil writes mostly about some few crops—about wheat and grapes and not about, for instance, hops and apples—and is careful in that same spirit to include a hymn to Rome’s native peninsula, some fifty lines in Dryden’s version, which give to his Augustan verses specifically Italian and cisalpine qualities (Virgil 1697: 2-187-246).

We are on the verge, then, of declaring the georgic proto-nationalist. “England,” Cowper whispers, “with all thy faults, I love thee still” (Cowper 1968: 2.206). And yet these localizing tendencies are undercut by some other of the poems’ persistent features. Grain fields and vineyards do boast a certain centrality in Virgil, but his poem nonetheless hops cheerfully from growing zone to growing zone, often letting the agricultural regions of Europe and beyond pass in review: Austria, southern Bulgaria, Ethiopia briefly, India more than once. The very emphasis on the earth’s geographical variation encourages readers to think of provinces in terms of their distinctive products, monocrops destined for export—variety, yes, but imperial variety, barely distinguishable from tribute: western Turkey “gives us” perfume; Georgia “sends from afar” the groins of beavers (Virgil 1940: 1.56; Virgil 1697, 1.87). The poem’s method is less localizing than it is encyclopedic and comparative, and this commits it to a language that is flexible and unspecified, even when it is enjoining readers to tend to the earth’s specificities: the language, that is, of “sundry places”—various places, no particular places (1.93). “The nature of the several soils now see, / Their strength, their colour, their fertility” (2.247-248). One might wonder, in fact, how extensive your landholdings have to be before you need to worry about “the nature of their several soils.” The georgic, that is, does not submerge us in some lexical byway, in the manner of later dialect poetry or regionalist fiction. Instead, it imagines as its ideal reader the kind of person who is able to shuttle between localities, precisely not a smallholder, but a traveler or imperial administrator. Poet and reader are joined together instead as explorer-colonizers, itinerant prefects surveying the agrarian empire in tandem. Virgil’s geopolitical aesthetic is to that extent not really agricultural at all, nor even terrestrial, but maritime, in a manner that cannot help but recall the epic: “Embark with me, while I new tracts explore, / With flying sails and breezes from the shore.” The georgic isn’t so much the epic’s competitor genre or land-lubbing opposite number as it is the latter’s amphibious extension: “coasting along the shore in sight of land” (2-57-8, 64).

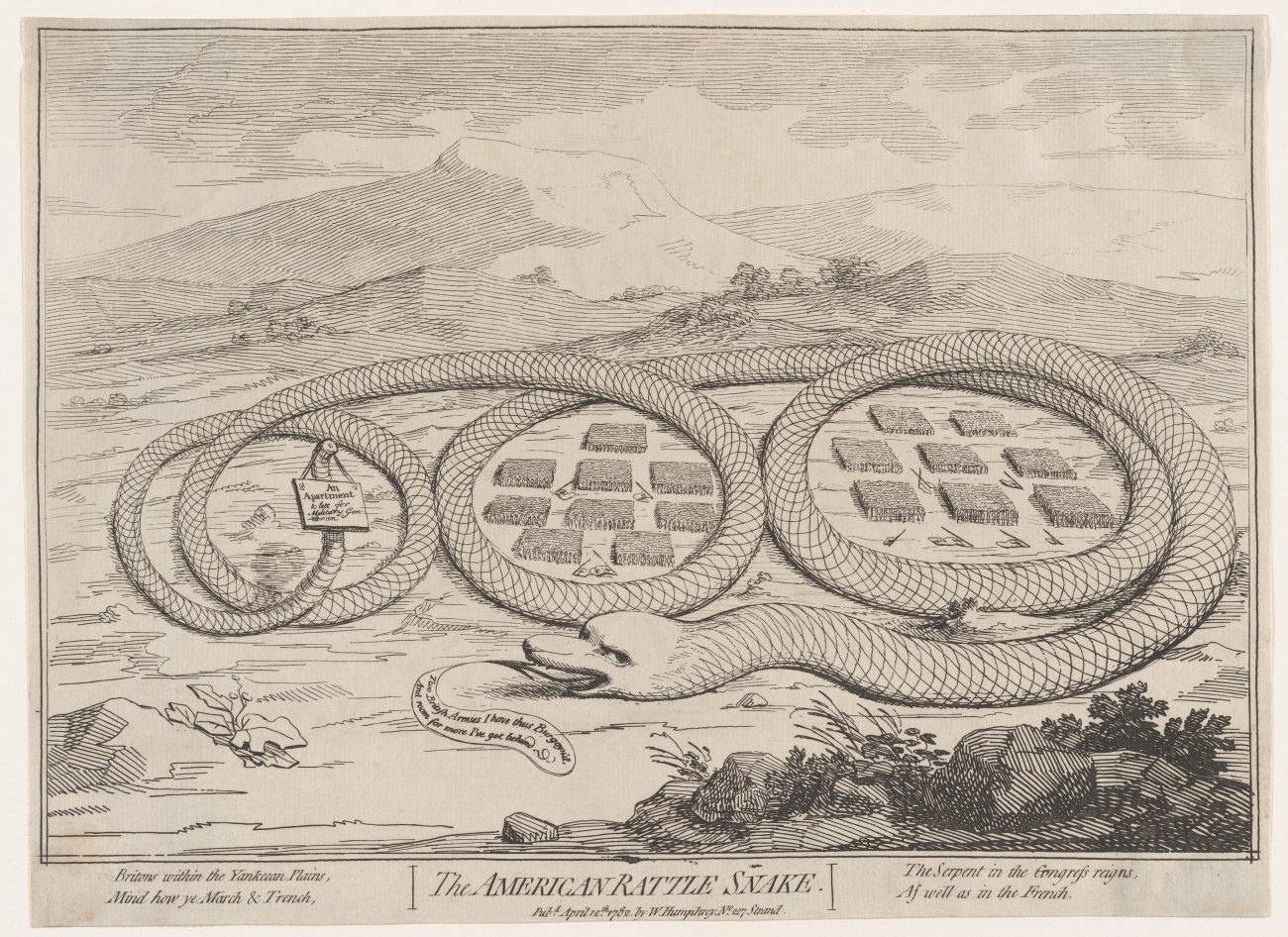

For Cowper we can just repeat the point: It makes no sense to see The Task as four thousand lines of ardently recollected feeling, and just because the poem is rooted in Buckinghamshire, it is not thereby closed off to the rest of the world. This should be entirely evident from the passage in Book 4 in which the poet describes tucking in on a winter’s night to read a newspaper. What immediately jumps out about these lines is that their register is not, in fact, journalistic, not even by eighteenth-century standards, but is high-flying and, again, epic. The entry into the poem of some provincial ledger or gazette is marked by an unexpected eruption of Dantean language: The argument at the head of the book calls this passage “The world contemplated at a distance,” as though every time we leafed through the morning edition we were out in the Beyond or the All, skimming towards the earth alongside Milton’s bad angel. If you turn to the politics section, you will see statesmen perched on the “mountainous and craggy ridge” of their ambition. If you read the reports from the floor of Parliament, your ears will ring with “cataracts of declamation.” If you so much as peruse the advertisements, you will find “Heav’n, earth and ocean plunder’d of their sweets” (Cowper 1968: 4.82) A newspaper, we read, is a “map,” its scope “vast,” its every article a landmass (4.50-100). And the poet, while he reads the newspaper, is in the position of the epic hero at the top of a summit: He is “peeping at the world … sitting and surveying [while] at ease / The globe and its concerns.” Cowper, in sum, has declared the newspaper—and not the novel, and nothing in couplets—to be the eighteenth century’s distinctive reinvention of the epic; or if you prefer, he has actively converted the one into the other by synthesizing its fragments into a vision of what the poem itself calls “the globe.” And if you notice this, then suddenly there will light up, throughout the poem, meditations on various un-English places: The poet describes the Bastille; he thinks out loud about India; he imagines himself as a native walking along a beach on a Pacific island. And most important for our purposes, he looks west into the Atlantic: “Yes, we have lost an empire—let it pass” (2.263). And, at the very end of the poem’s first book, hence in a highly stressed position: Behold “our arch of empire”—“a mutilated structure, soon to fall” (1.773-774).

The poem, in other words, has a sharp sense of political crisis; the American war is at least the most obvious symptom of that crisis. What we have to see now is that the georgic—the poetry of rural labor—is a way of imagining a way out of the disaster. One of the many things that puzzles me about the scholarship on Cowper is how seldom it bothers to account for the poem’s title, which, after all, is “the task”—as in, the chore, the job, the business at hand. Yes, we have lost an empire; now here is the task. I think this is the conception with which the poem is best read. But Cowper’s achievement here is actually rather hard to name. Much about his procedure is pedestrian or genre-bound: We can’t exactly congratulate Cowper for having produced detailed descriptions of rural work or for teaching us to prefer the working countryside to the consuming and imperial city, since this is in some sense simply what georgics do. That a georgic ethos of toil should be a regenerating alternative to the corruptions of empire is not in the least surprising. The best thing about the countryside in February is that all nabobs have left for London. But Cowper has nonetheless written one weird georgic, since this poet was not a farmer and does not even pose as one. Where Cowper is most interesting is in the deviations he introduces to the form. His georgic remains a poem of rural work, but what those words mean has now changed rather drastically, as Cowper devises a way to anchor the form in other country types—not quite the farmer—but the hiker and the gardener, who will function now as the former’s cousins or utopian proxies.

That a hiker could claim membership in utopia should be clear to anyone who has ever donated money to the Sierra Club. The Task begins with a teasing history of Things You Sit On: rocks, rough stools, chairs, cushions, and eventually, in the eighteenth-century present, couches, which Cowper turns into the emblem of a corrupt consumer economy, a symptom of “pamper’d appetite obscene,” furniture’s equivalent of the gout (1.104). Hiking, then, enters the poem as one term in an organizing antithesis, as the anti-consumerist option, the opposite of upholstered recumbence. You pack into the uplands because they take you further away from the balls and the card tables and the rococo rotundas of urban pleasure gardens. As soon as the poet sets off on his ramble, then, The Task begins working in two historical modes at once. A contemporary antithesis—the choice between consumer culture and rural virtue—comes in to supplement what up until that point had been a historical succession (of economic stages as reflected in their representative movables). The image of the weather-hardened, pillow-hating rustic obviously activates a familiar republican critique of luxury—and, in 1785, would have easily called to mind the home-spinning and import-boycotting Americans—though perhaps the more precise way to conceive of the matter is to say that Cowper is grafting a contemporary antithesis onto a historical progression. The poet’s walks keep alive some earlier period in history, before luxury. Indeed, his own biography replays the Story of the Ages. I used to hike a lot when I was a boy, the poem says. “No SOFA then awaited my return, / Nor SOFA then I needed” (1.126-127). Both his childhood and the pre-capitalist epochs were the ages of no-sofa, and he time-travels back to these days every time he treks across his neighbors’ fields.

This all seems plain enough, and yet it is really quite puzzling. The georgic typically comes to us as the poetry of work; work is thought to be its defining feature, the engine of its own anti-consumerist energies, and the service that this ancient form rendered to England’s rural party in the eighteenth century’s running battles between Country and City or Country and Court. The georgic view of history is basically Hegelian or Baconian or Stakhanovite, describing as it does how early, post-Arcadian humanity established its toiling dominion over the earth. The genre’s major poems are clangorous with what Dryden was as early as the 1690s already calling “industry” (Virgil 1697: 1.207) which names both human diligence and a certain power over the earth’s resources. Georgic humanity works and puts everything else to work, these geroii truda of the Neolithic, who devise “toils for beasts,” and make trees “swim,” and who would, given the chance, teach horses to hammer their own shoes (1.211). Here’s Virgil in a twentieth-century translation: “Yes, unremitting labor / And harsh necessity’s hand will master anything” (Virgil 1940 1.145-146). Dryden calls this labor “endless” (Virgil 1697 1.218).

Judged by these standards, the rambler is a peculiar figure around which to launch a critique of luxury or consumption, because he is not a worker, not productive, which means that once you’ve spotted hiking’s centrality to The Task, you might wonder whether the poem is really a georgic at all. The poet may be walking across other people’s farms—and so retain some kind of sentimental attachment to or even physical connection with them—he may have in some entirely elective sense aligned himself with a rural social order and its culture—but he is the non-working term within them. He is not saying to the consumer-elite: You neglect your duties while I work. He is saying: I prefer a more strenuous form of leisure. At one point he boasts that, though old, he remains energetic. He can walk fast and climb steep hills, and this effort is “no toil to me” (Cowper 1968: 1.139) But that line is of course unintentionally literal. He really isn’t working. Getting winded is his play.

Here’s one way to solve the puzzle: It would be possible, at least, to see the figure of the hiker as a platform from which to launch a radicalized critique of consumption, in which case we could think of The Task as a kind of georgic in extremis. Hegel, when introducing his “System of the Individual Arts,” tries to explain why the appealing idea that each sense produces its own art form is in fact wrong: Only some senses manage to produce art. There is no taste-art, for instance, and no smell-art either, the claims of chefs and perfumiers notwithstanding. The distinction for Hegel is a straightforward matter of consumption: Nothing that you stick in your mouth could be art, since to eat an object is to destroy it, and Hegel declares such violence to be incompatible with the aesthetic attitude. Smell, too, is a kind of unhurried consumption; it involves the object’s decay, the gradual detachment of its molecules, their noseward wafting. You snuffle an aromatic object at its slow expense. Sight, in these terms—in terms, that is, that we ordinarily associate not at all with Hegel—is the one fully utopian sense, the one that does not negate its object, that takes in the world and still leaves it lovingly inviolate (Hegel 1975:2.621-622).

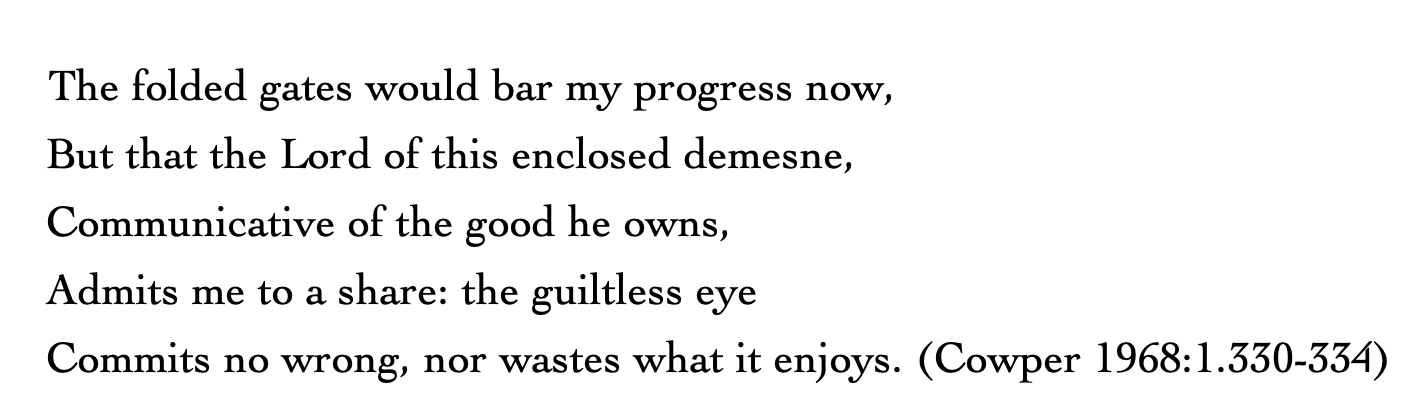

It is this claim that we find Cowper making on behalf of his rambler, a claim that both allows for a political reading even of the eighteenth-century picturesque and readmits historical considerations into Hegel’s uncharacteristically ahistorical divvying up of the body. Cowper says that he is allowed to hike on properties that are off-limits to other townspeople:

“The guiltless eye”: There’s a lot to be said about this, since the passage preemptively situates Hegel’s claim within the history of enclosure and by extension the battle over the commons. The hiker-aesthete is welcome where the cottager or smallholder, pursuing some customary right, can no longer go. The aesthete is to that extent a substitute for the peasant—he occupies roughly the spot where we would expect to find a peasant in a georgic poem—and yet he does not simply replicate the peasant’s position; the aesthete (in proper Heideggerian or Adornian terms) has a non-extractive, non-instrumental relationship to the land, and so is no competitor to the enclosing landlord. These lines insert a language of ease where a georgic is otherwise obliged to discover toil, but it makes that leisure redemptive, if also unthreatening, generating a notion of Gelassenheit or aesthetic appreciation in opposition to work and consumption both, which become just two forms of “wasting.”

Still, there is one way in which production returns even into the poem’s hiking passages: As a boy, Cowper writes, he liked to root around for food while he was hiking—crabapples, say, or plums—“hard fare,” he calls it, in ways that make the memory visible as a variant of the poem’s anti-consumerism: honest vittles rather than the sugary tea of the double Indies (1.123). If the hiker isn’t a farmer, then, if he doesn’t seem properly a part of England’s agrarian economy, then he might instead be an echo of some earlier history or alternate present: of gathering and foraging economies, as witnessed by English settlers in the Americas, or of commoning economies as they survived in England well into the period of enclosure. He remembers as a boy doing what commoners and Indians did (or continued to do): collecting berries and mushrooms and puffballs and nuts.

So what can be described as arduous play can also be described as the kind of agreeably light work suited to boys and aesthetes. It is one of the signatures of Cowper’s poem that it is drawn to such intermediate categories: “industry enjoy’d at home” or—the most telling phrase, this one—“laborious ease” (3.356, 361). This is all rather interesting, and dialectically entertaining, but none of it is clean, since it is the fate of such medial categories to be messy and unstable, and it is Cowper’s plight that other figures can plausibly be included under these headings, alongside the hiker: gypsies, whom he doesn’t like, because they “prefer / … squalid sloth to honorable toil” (1.578-579); or Tahitians, whom he does like, because they make do with “simple fare” and “plain delights” (1.646); or a crazy, homeless woman, who is The Task’s other designated hiker and as such the poet’s most conspicuous double: “There often wanders one,” who “roams / The dreary waste” (1.535, 546-547) It’s worse than that: Cowper often seems to be attacking the gentry, sometimes on behalf of what he himself calls “the poor and the despised” (3.286-287). But sometimes he writes unmistakably from the position of a landholder: It’s good to get up, have your woman feed you, read a book, sometimes out loud. Or you can work outside—except he doesn’t really mean work outside. A man can go into the garden “conscious how much the hand / Of lubbard labor needs his watchful eye, / Oft loit’ring lazily if not o’erseen” (3.399-401). Cowper, in other words, is fond of that intermediate category—whatever is neither leisure nor work. And to anyone who is drawn intuitively to the liminal, this is going to smack pleasantly of the dialectic. But one of those things that is cheerfully in-between—that is neither leisure nor work—is the management of other people’s labor. Cowper gives us the poet-aesthete as overseer; the work of the eye, which we were earlier asked to understand as the fond gaze of aesthetes, now turns out to be the boss’s humorless squint. Maybe we can take the point further still. The poem’s many picturesque passages communicate a certain mild Spinozism, but they also suggest a stance of delectation, which we can’t quite call a consumer relationship to the landscape, but which is nonetheless haunted by its similarity to consumption and ease. One of the earliest things the poet tells us, upon first attempting a landscape description, is that he has kept his “relish of fair prospect,” at which point the hiking boy-savage who has been spared the corrupting ease of Sofa England comes dangerously close to reversing into his world-devouring opposite (1.141). A reader thinks the poem is setting up a distinction between consumer luxury and yeomanly toil; this turns out to be a distinction between indolent play and more strenuous play, which in some ways resembles work; but then that latter stops even resembling work and becomes simply an elevated form of indolence.

The Task, in sum, seems to give us the rambler as utopian figure, but is finally more interested in the oscillations that creep into the gap between the hiker and the farmer, as the hiker tries, and fails, to ward off his sundry semi-industrious doubles. The poem is to this extent less an early exercise in eco-consciousness or the ideology of the backwoods trail than it is an examination, perhaps unwittingly, of that ideology’s instability. A poem that seems to be organized around a clear antithesis—the corrupt, commercial, and imperial metropolis vs. the plebian countryside, where nature still harbors the power of renewal—turns out to be a work that marks the near impossibility of this pantheist position, preemptively blocking the very Wordsworthian stances which Cowper is generally regarded as having made possible.

Here, at last, we might think we’ve found something distinctive in Cowper—that he makes the georgic wavery and self-interrogating. But then it turns out that these qualities, too, were there in the genre all along. At its most overtly political, the georgic often goes in for legends of the rural golden age: in the beginning, the world was all an orchard, and there was no war, and god himself lived on earth, and even he was vegetarian. A recent anthology of Virgil in English reproduces from Book 2 of The Georgics only that volume’s famous glimpse of paradise, but this it gives in four different translations (Virgil 1996). These lines are plainly describing something more than the remote past; it can come as no surprise to find the poet claiming that the Augustan-era countryside still retains something of its primal blessedness, that it is, compared to the imperial metropolis, a less lapsed place, spared the pathologies of the city, relatively calm, austerely content. What should surprise the reader, however, is that The Georgics’ figurative language, in the balance of the poem and there pervasively, is impossible to square with this vision of the countryside as peace-loving and serene. Virgil often wants to describe his Italian farm country as the anti-imperial term within the empire, and yet he habitually describes the farmer as an emperor—as a war leader or strongman or colonizer, and all the more so in Dryden’s landmark translations from the 1690s. If a farmer’s plantings are growing too quickly, he can bring in his sheep and goats “to invade / The rising bulk of the luxuriant blade” (Virgil 1697: 1.165-166). He will need, in fact, to be permanently on his guard, since “sundry foes the rural realm surround” (1.264). A herdsman, meanwhile, will have to play cop or sovereign to his fighting bulls: “The stooping warriors, aiming head to head, / Engage their clashing horns: with dreadful sound / The forest rattles, and the rocks rebound. / They fence, they push, and pushing, loudly roar: / Their dewlaps and their sides are bathed in gore” (3.340-344). A beekeeper, for his part, presides over a “nation” made up mostly of “trading citizens”; if he establishes a new hive, he can be said to have planted a “colony” (4.10-28). And a farmer moving into wastelands can make oaks and elms, the “tribes of trees in forest” “change their savage mind / Their wildness lose … / Obey the rules and discipline of art” (2.72-74). You can think of The Georgics as an ongoing meditation on the ways in which the backcountry was and wasn’t part of Rome’s militarized trading empire. Officially, they had nothing to do with one another, but every simile confesses their continuity.

This opens up into a larger observation. We might want to think that the epic and the georgic are competitor genres, and sometimes, indeed, they are, not least of all in the epics themselves. Homer’s imitators, from Virgil onwards, have almost always said that they would rather be writing about farms or landscapes. I had been hoping to sing a song about goatherds, but I have to talk instead about war and rage and the flight of refugees. If we simply assimilate the georgic to the epic, which is the contrary temptation, we are likely to read right past this stance of reluctance. Most epic poets, even as they push unenthusiastically out to sea, are haunted by a rustic wish. What is at stake in the choice between epic and georgic is—or can be—two fundamentally different ways of understanding the land: who owns it, who should own it, how it should be used. Wordsworth’s “Female Vagrant” (1798), which is another rare work on the American war, turns on that distinction. The poem tells of an English peasant woman whose father loses his customary rights to fish in certain waters and is then forced off his land; she heads off and marries a worker; he can’t feed the family and so joins the army; and she joins him when he is sent to fight in North America, where he dies; the rest of the poem she spends wandering the Atlantic, spectral and catatonic. What is perhaps most intriguing about the poem is the way in which Wordsworth pulls from earlier English writers in order to mark the changes in his wanderer’s life; it’s as though the stages of her biography corresponded to moments in literary history, which in turn corresponded to major period’s in the progression of the English economy. When she describes the customary economy at the moment of its historical eclipse, the economy her father belonged to before he was expropriated, when she was a child, Wordsworth adopts a pastoral-georgic idiom borrowed unmistakably from Robert Herrick. But when she describes her life in the Atlantic, the poem starts citing Milton instead, and at a clip. From smallholding to oceanic exile; from Herrick to Milton; from rural poetry to epic: The important point is that these shifts are at once ingenious and completely typical of the century. The poetic genres themselves seem to insinuate a social history or a periodization, where country poetry describes a pre-Atlantic farm economy and the epic describes the commercialized and militarized ocean. The two genres seem to encode different ways of making sense of the British social order, which means that modern scholars are themselves forced to choose between literary forms, though they almost never conceive of their writing in these terms. The social historians, after all, have never settled on a term to describe whatever it is that preceded industrial capitalism. If you prefer terms like “mercantilism” and “empire” and the “fiscal-military state,” then you are writing history as epic. If, however, you prefer a term like “agrarian capitalism”—or if you write about the American colonies’ imperfectly capitalist western back settlers—then you are writing history as prose-georgic.[iv]

And yet what Cowper and Virgil and indeed most of the other major poems in the genre all demonstrate is that the georgic and the epic need not compete; that they are easily intergrafted; or, at the very least, that the epic will tend to endure in the georgic, as a persistent and globalizing instability within the form’s poetic sheepfolds and willow stands. The Virgilian collapse of the georgic into epic is an event that the genre undergoes time after time and as it were compulsively. There are at least three different ways the two muses can coincide: Often in an epic, some character, usually in the company of a guide, will summit a peak or tall hill and survey the territories stretched out below; at moments like this, the epic mutates into something like a higher-order topographic poem, in which modes of lyric description usually reserved for single valleys or river bends open up to encompass entire continents and hemispheres. Alternately, one form can absorb the other. When Joel Barlow wrote The Vision of Columbus, he incorporated the georgic as a way of describing advanced agricultural society in the Americas. Other poetic modes describe other modes of production: The pastoral describes hunting-gathering Indians; the epic in its martial and heroic guise describes both the Spanish and the British; but the georgic describes the English and German settlers and helps the reader feel why colonization has been necessary: because it brought to the new world people willing to improve the land. Barlow’s is something like a georgic epic, a vision of world farming.[v] But then equally, nearly all the long georgic poems contain passages, as in Virgil, where they shift into an epic register—and that’s because they nearly all have their imperial moment, where they imagine Britain’s farm economy exporting some agricultural commodity or, more vaguely, envision Britain’s farms as the source of the nation’s naval might. The English will export cider around the world, and it will replace wine. Or as Philips has it: “to the utmost bounds of this / Wide universe, Silurian cider borne / Shall please all tastes” (Philips 1708: 2.668-669). The poetry in question adds up to a kind of imperial georgic, and it is rampant, one of the dominant idioms of early eighteenth-century verse: at once heroic and yeomanly, countrified and earth-spanning (O’Brien 1999).

Knowing this should allow us to say why it is important that Cowper has in large part taken the georgic away from the figure of the farmer and reassigned it to the gardener, because the latter—the man who actively and individually tends his fragile plants—enables The Task to rebuild the accustomed joint between the georgic and the epic to new specifications. If I tell you now that Cowper’s solution to the American crisis is to grow cucumbers, you’re going to think I’m being silly, but I’m not. We need first to reckon with one more fundamental fact about Cowper. He has written a winter poem. It’s a georgic, but it’s a winter georgic, which is itself a little unusual, because winter is the season least hospitable to the georgic as a form; winter is the farmer’s imposed downtime. And if you know the literature of winter, and you spot early on that Cowper’s poem is about winter—the books mostly have names like “The Winter Evening,” “The Winter Morning Walk”—then you’re likely to begin the poem with certain expectations. When the poet James Thomson describes winter, some half century or so before Cowper, he makes the season sound like an annual dose of Armageddon. Every winter rehearses in advance the coming ruin of Europe; the land is laid waste; storms and wolves attack the farms like Indians or Goths; the cosmos itself seem to degenerate into strife or chaos, as though there were no God. It’s a remarkable poem in its own right, and an ingenious one. To the observation that in winter no-one can farm, Thomson appends the observation that savages also don’t farm, and sums these together into the idea that winter turns Englishmen into Mohawks, with the further consequence, therefore, that spring repeats the history of colonization every year, by turning winter’s savages back into farmers.

A person picking up Cowper for the first time could reasonably expect Cowper to have absorbed some of this language: It is winter. We have lost an empire. It is England’s winter, a blow to settled life. But here’s the thing: What most stands out about Cowper, when we compare him to Thomson, who is his proximate model, is that he does not describe winter as the end of civilization, which would have been easy to do given the sense of imperial crisis that prevailed in Britain in 1785. The most sustained georgic passage in the poem describes the poet’s efforts to grow winter cucumbers by planting them in manure under glass—lines, that is, that will teach you how “To raise the prickly and green-coated gourd / So grateful to the palate” (Cowper 1968: 3.446-447). There are at least two different ways to read the passage:

If we follow the poem’s literal and referential meanings—and there’s good reason to; the language is close and detailed and not, in these lines, much given to allegorical overlay—then we can take it seriously as a description of farm work, in a manner beloved of Marxist literary critics, who, indeed, have often liked such poems because they seem to de-fetishize agricultural commodities. They remind readers that even seemingly natural objects require human labor, and to that extent are the opposite of all those old pastoral poems about fruit that flings itself from the trees into the open mouths of passing dukes.

But then so much of the poem up until this point has been historical and moralizing that it is impossible not to carry the political concerns of the rest of the poem over to these descriptions. The greenhouse becomes the key image of reform. Cowper will show you how to make something grow in down time, in the period of death, winter or two years after Yorktown, teaching “th’ expedients and the shifts / Which he that fights a season so severe / Devises” (3.559-561). The winter farmer—like the Calvinist evangelical—is the one who can make something valuable grow in a dung-heap. There is, of course, one type of farm-work that does get done in the winter, and that’s pruning, which Cowper describes like this:

I just want to point out that it is overt allegory of lines such as these which prompt a political reading of the entire passage on gardening. England will get through its imperial winter if it finds new ways to grow and also if it gets out what Cowper calls “the knife.”

We can connect the two—the poem’s literal meanings and the allegorical overlay—since the political reform the poem is implicitly recommending is, as ever in the georgic, agrarianist, an England returned to honest agricultural labor. But here we have to ask: What, other than cucumbers, does Cowper want a reformed, post-imperial England to grow? Cowper, we still have to keep in mind, is describing a gardener and not a farmer. More to the point, he is describing a green-house—he actually uses the term—and at times, he seems to be laying out a poetic program of import substitution. A green-house, after all, will not only allow a winter farmer to grow summer crops. It will allow an English farmer to grow tropical fruit, as well. It is thus a way of contracting the economy without giving in to a cultural nativism, of dealing with the loss of empire and turning that crisis into its own solution. The greenhouse, often enough outside of poetry turned into a permanent imperial shop window, will now substitute for the colonies.

These lines, and the glassed-in cornucopia they describe, overturn a half dozen settled views at once. They call into question literary history’s portrait of Cowper as the period’s premier headcase and literary gloom-smith, modeling as they do, in the middle of the official emergency of the 1780s, after Britain’s worst military defeat in generations and the collapse of three successive ministries, a buoyant disregard for bitter winds or bad circumstance—a “not needing to fear.” The passage will not on its own invalidate our sense that British nationalism ramped up in the eighteenth century under this or that Pitt, and yet Cowper’s unlikely and antithetical image of an internationalized boondocks, not cosmopolitan but cosmoagrarian, does make clear that English writers were at the very least capable of imagining a different Britain, even while most were busy wave-ruling and not-being-slaves, a hospitable island open to “foreigners from many lands.” More: If, a generation back, you had examined the historiography of the American Revolution—if, I mean, you had read extensively around in the career-summarizing monographs produced by major scholars—a certain divide would have obtained: American historians, at least before the Atlanticizing and trans-nationalizing turn, have almost always thought in nationalist terms and have usually competed to tell the most saleable origin story. And it is the British historians who, less drawn to the event anyway, were until recently more likely to think of the Revolution as an imperial occurrence, or even as a world war, inserting the American struggle into a global perspective.[vi] But in the 1780s, it was the Americans who were writing epics—there were those two important ones—and these both foretell, in that genre’s accustomed prophetic mode, the rise of US global power: the founding not of a nation but of a world order. Collectively, then the long poems of the decade reverse our current expectations, and the result, to most readers, will sound more like 1960 than 1785: Britain has lost an empire and will need to re-ground itself as a polity. America, henceforth, will rule the world. But then even Cowper’s regionalist Anglo-georgic is evidently not a poem of retreat or of nationalism-on-the-backfoot. It is a poem of localization and containment, which is something rather different—a poem that describes a new way, in the wake of imperial crisis, to get the globe into an English locality—and this is true simultaneously at several different levels: pineapples in the greenhouse; the newspaper in the country cottage; the epic in the georgic, but now in an anti- or at least post-imperialist mode, rather than an expansionist one. “The Azores send their jasmine”: That’s Virgil’s language, for sure, and yet Cowper has nonetheless devised a way to get his epic roll-call of the world’s plant life to model an openness to the globe and not a Cyclops-blinding hostility to it. Cowper undertakes the familiar articulation of the epic with the georgic, but via an unfamiliar revision: not the georgic’s imperial apotheosis, which leads to the world dominion of marchland apple juice, but just the opposite, which is empire-and-epic’s knee-capping diminution, its shrinking back to uncolonial proportions. If you build enough greenhouses, then South Africa need send only a single shrub or specimen, and the English, like a country poet in a snowstorm, can stay home.

[i] Cowper’s madness is the central concern of all the biographies. In addition to King 1986, see esp. Cecil 1930.

[ii] See, for instance, King 198: 115: “In many ways, Cowper is a lyric poet … who strayed into narrative poetry. The Task’s finest moments are in brief, intense passages where the poet speaks directly of his finest subject: himself.”

[iii] See also Dryden’s translation of the same passage, at 1.81 (Dryden ????).

[iv] Military and colonial history borrow so routinely from epic poetry for their stock formulas and scenes that no handful of examples could document the debt. Anyone wanting to follow out this point, though, should inspect the work of Arthur Quinn, who attempted, in the early 1990s, to translate the scholarship back into a prose epic (Quinn 1994). The ideology of the eighteenth-century English georgic is agrarianist almost by definition and often yeomanly. The stock scenes that carry these doctrines—of farmers clearing land, figuring out new crops, &c—recur in almost any popular treatment of colonial America and even flare up in a book like Changes in the Land (Cronon 1983).

[v] For the Native American pastoral, see, for instance, 2.19-28; for the British military epic, see 5.211-222; the white settler georgic runs throughout, but is especially conspicuous at 4.383-386.

[vi] For the latter, see Mackesy 1964 or Bayly 1989. And against them we can almost shout a roll call of American revolutionary historians: Beard, Jensen, Main, Young, Wood, Middlekauf, Breen, Nash.