Exclamation points have played a distinguished role in the history of Marxism. It helps if every other one is upside down. The exclamation point is the mark of solidarity, of commitment, the manifesto in a single keystroke. We don’t, it is true, often see them in Marxist theory, as opposed to, say, Marxist graffiti. But Hardt and Negri’s great communist trilogy is crammed with exclamation points: “One big union!” “Papier pour tous!” They even quote the spray paint from a Paris wall: “Foreigners, please don’t leave us alone with the French!” There are pages where Hardt and Negri’s prose fairly bursts and pops with exclamation points, as though they were writing Xhosa. Exclamations, not all of them marked, are this writing’s stamp, its most conspicuous stylistic feature, and as such demand to be accounted for. What are they doing there? What is their effect? What’s the difference between a book with lots of exclamation points and one without?

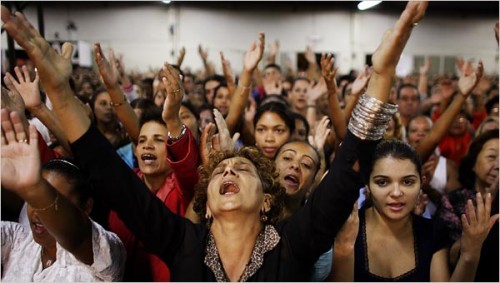

This clearly has something to do with what Hardt and Negri call “the joy of being communist” and what their intellectual forebears call “gay science”—the sense, that is, that a radical politics cannot take root in the thin soils of melancholy and umbrage, but must nourish itself instead on the sheer exhilaration of collectivity and creativity and free innovation. The exclamation point is a streak of that delight, the mark of its strong feeling and guileless spontaneity. It is a smudge of affirmation, of really, really meaning it. More: The exclamation point is meant, like a rocketship with its falling booster, to propel readers back out of the text, to shunt them back into a world of real objects or at least to smash them against the bedrock of the writers’ sincerity. It is through punctuation marks that even ordinary writing overcomes its own ingrained positivism, its tendency to reduce the world to rubble, static things and discrete events. Commas introduce relation to the simplest sentences, as periods do disjunction. Dashes and semicolons establish relation and disjunction at once; they sunder even as they join, which makes them the typographical face of dialectical thought. Question marks summon an Other into being and then send that Other out to scrutinize the world with fresh eyes. Exclamation points do the same in the form of a command. They indicate the end of the text as text, placing some demand on us as readers that we cannot fulfill as long as we continue in that contemplative state, as long, that is, as we do nothing but read. This accomplishment, however, is also the exclamation’s failure, for the exclamation point, as the signpost to something outside the text, reveals itself to be external, imposed from without, and thus a positivity in its own right. Whatever cannot be done within the sentence has to be done to it. The exclamation mark is the sentence’s fate, its doom, a grenade lobbed by an unseen hand.

The exclamation point’s natural habitat is now the children’s book and the supermarket tabloid, the comic balloon and the screaming headline, and this is its finest boast. Hardt and Negri’s exclamation points borrow their energies from these forms, from the young and the poor; they mean to put such energies in the service of thought. The exclamation point is similarly at home in advertising, but from this sphere exclamatory thought borrows only its fiercest contradiction, its con, its intertwining of joy and command. The exclamation point is the billy club of Konsumterror. It is, after all, children and the poor who get ordered around with impunity, and the shouts in storybooks or supermarket papers find their echo in a parent’s rebuke or barking foreman’s order. There is a poem by Robert Herrick, first published in the 1640s, called “Corinna’s Going A-Maying.” It is one of the period’s most winning pastoral lyrics, some seventy lines on England’s customary spring celebrations, full of kissing games and cream-cakes and country cottages hung with blossoms. The first thing that strikes one about the poem, however, is that its title is a misnomer: The poem is addressed to Corinna, the poet’s lover, who refuses to get out of bed and is thus in danger of sleeping through the May games. Corinna precisely isn’t going a-Maying; such is the entire occasion for the poem. The poem’s heading, in other words, is oddly reversed, and anyone noticing as much has a chance of also spotting the poem’s key lines, which casual readers inevitably skim past. About halfway through the poem, the poet describes the flowers on the houses and the crowds in the fields and then asks: “Can such delights be in the street / And open fields, and we not see’t? / Come, we’ll abroad; and let’s obey / The proclamation made for May.”

It’s that last line that should give us pause. Rural games were, improbably, one of the great political flashpoints of the early seventeenth century. The games were ordinarily played on Sunday afternoons and on the old medieval feast days; reform-minded Protestants accordingly saw them as Catholic, crypto-pagan holdovers and wanted them abolished. But the Stuart kings, cloaking themselves in a kind of agrarian populism, the way a U.S. president might chow barbecue or sport a cowboy hat, promoted the games in official legislation, not mandating them exactly, but encouraging them and forbidding the Puritan opposition from trying to spoil the fun. The Crown’s stated rationale for sponsoring the maypoles and morris-dances was blandly functional: The games would bind the peasantry to the state and the state church; they would prime the bodies of the poor for war; and they would keep the poor from organizing in opposition to the state (in the taverns or conventicles in which they would otherwise while away the week’s few spare hours). This, then, is the proclamation in question: “Let’s obey / The proclamation made for May.” The merriment that the poet has been advocating turns out to be obligatory. Delight modulates into obedience and thus into un-delight. A poem that had seemed to hum and croon of rural amusements mutates into a poem about law and its enforcement; it seems a shame that Herrick never wrote a Corinna-cycle—“Corinna’s A-Paying Her Taxes” and so on. If, upon running smack up against the state, you go back now and begin reading the poem again from the start, you will surely notice that it is, in fact, made up of nothing but commands. Its pitch is that of a parent hectoring a teenage layabout: “Get up! get up for shame!”—modern editions are quick to supply those exclamation points. The poem’s title is not a statement of fact, for Corinna, to her credit, never budges; she persists in her springtime, sitdown strike, a kind of consumer boycott on the wildflower. Her genuine idleness—and not Puritan asceticism—is the liberating alternative to this royalist poem’s regime of compulsory pleasure. The title, by contrast, is the king’s wish, the law’s resolve. One must imagine it spoken through clenched teeth: Corinna is going a-Maying.

If there is a politics of the exclamation point, it is here. The exclamation point is the mark of forced Maying. It always bears a trace of the imperative, of coercion and prohibition, even when it seems only to revel. So this is what we need to look for any time we are enjoined to be jubilate, the moment of conscription that attends joy’s grin and flush. Hardt and Negri want us to go a-Maying, though they have a different May Day in mind. They summon us to gay science. They want us to Do the Dew. “Big government is over!” So let’s ask: What is gay science’s command? What does it want from you?

• • •

What does gay science want from you? We can start with the term itself, or rather with its provenance: Where does the phrase come from? What is the history it carries with it? The term comes, first of all, from Nietzsche, for whom it means something like the free and creative vocation of thought. This notion is trickier than it may at first seem. We normally think of knowledge as coming under headings of truth and falsehood, accuracy and error. Knowledge is supposed to be knowledge of something—of songbirds or Balzac or Kondratieff waves. It is thought that corresponds to really existing conditions in the world; it is the means by which the mind assimilates that world. To speak of “the free and creative vocation of thought,” then, is to call our attention to all those modes of thinking that do not function like knowledge, that do not report and describe and depict, that mean instead to bring new things into the world. But to call this creative vocation of thought “gay science”—gaia scienza, joyful knowledge—is to bring knowledge itself back under the rubric of productive thought, to strip it of its character as knowledge. If we follow Nietzsche, we must stop judging knowledge by the exactness of its representations. Rather, we must judge even knowledge by its non-epistemological qualities, its capacity to engender new forms of life, so that an innovative blunder or lie is always to be preferred to a conformist truth. That is what gay science wants from you, and the term will name the utter elation of this antifoundationalism, the thrill of a world without ground, without factual or ethical constraint.

But the phrase is not, in fact, Nietzsche’s coinage, so the question simply re-poses itself: Where does the term come from? Where did he find it? It turns out that the phrase—not gaia scienza, as Nietzsche has it, but gay saber—refers to the Provençal troubadours of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and means the art of composing love poetry. This piece of information immediately suggests two further points: First, it clarifies Nietzsche’s argument. Gay saber is the science that is not science, knowledge understood as art. Nietzsche has selected from the history of European culture the phrase in which epistemology most obviously gives way to aesthetics. The only science that mattered would be indistinguishable from poetry. This, in fact, is a commonplace of Nietzsche commentary. The second point, then, is more curious because less commonly made: Nietzsche doesn’t borrow his term from just anywhere; he borrows it from medieval court culture. And taking this point seriously will bring into view Nietzsche’s pervasive medievalism, his thoroughgoing preoccupation with feudalism and the warrior nobility. Thus, even if we confine ourselves to the pages of The Gay Science itself, we will find, not only a collection of original songs, appended to the main text and designed to give the book the appearance of a medieval chansonnier, but endless talk of “the noble person,” men working “by force of arms,” “conquerors,” “descendants of old, proud families,” full of “reputation and honor,” the “knightly caste” who “treat each other with exquisite courtesy,” “aristocratic taste,” “a warlike soul,” “cultures with a military basis,” “refinement of noble breeding,” “men of leisure who spend their lives hunting, traveling, in love affairs, or on adventures,” “men of violence,” “bold and autocratic human beings,” “human beings who give themselves law.” So what does gay science want from you? It wants you to be a nobleman, to commit yourself to the refeudalization of Europe. The fit Nietzschean reader must function “as the dutiful heir to all nobility of past spirit, as the most aristocratic of old nobles and at the same time the first of a new nobility.” Nietzsche wants to dub you.

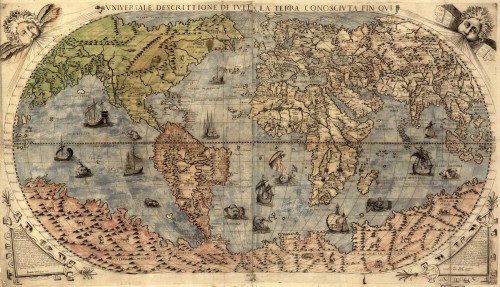

Gay science, in other words, is a machine for generating Quixotes, untimely aristocrats or noblemen without portfolio, ecstatically living out their creative delirium and made incomprehensible to others by their outlandish passions. It is fundamentally atavistic, designed to foster a “recrudescence of old instincts,” to “restore honor to bravery,” to conjure the “late ghosts of past cultures and their powers,” who will appear now as “rare human beings.” Nietzsche is philosophy’s own Lord Baltimore, who, in the 1630s, tried to revive feudalism on the eastern shore of North America: He obtained a land grant from the English crown on the model of an eleventh-century palatinate; named the territory Maryland; and then carved the region up into estates, complete with serfs and seigniorial rights and the rituals of sworn fealty. Maryland was meant to be feudalism’s Massachusetts, the experimental ground of an aristocratic utopia. The gay science, in these terms, offers itself as a Chesapeake of the mind. It is, in Nietzsche’s own words, “a strain from the old older of things European…a seduction and return to it.”

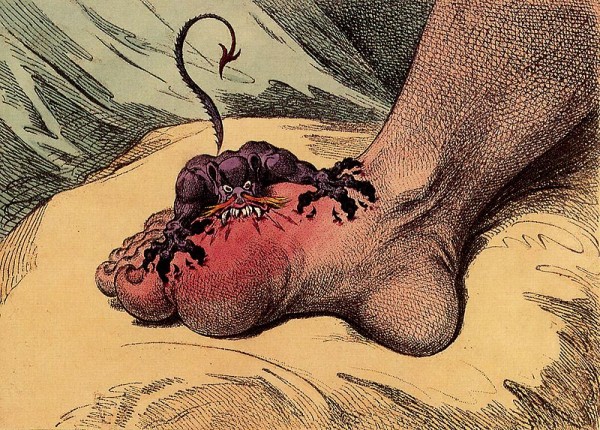

The notion of history that underlies this project is worth elaborating. Nietzsche’s writings, whatever their fragmentary character, produce a comprehensive account of European development, and the pivot point in that history is the rise of the absolutist state and the court nobility. The noblesse de robe stand at the beginning of Nietzsche’s modernity narrative, as Descartes does for Heidegger and primitive accumulation does for Marx. What’s at issue here? The problem, as Nietzsche sees it, is that the court nobility—all those chancellors and councilors and Keepers of the King’s Chamberpot—arose at the expense of an older, knightly caste, who were not bound to the monarch or were bound only by ties easily cut. At court, then, the feudal warlords allowed themselves to be turned into Jews, relinquishing their autonomy in exchange for the dubious honor of serving the king, lord of lords, as his Chosen People, the sticking point here being, of course, that a Chosen People always lets someone else do the choosing, so that its very claim to privilege secretly admits defeat and dependence. The nobility became just another people of the law. This transformation, usually dated in Western Europe to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, actually functions as the culmination of a much longer history, which can be recounted in a few different ways: As the great social historians tell it, this is a story, above all, of institutional changes: In the ninth century, there arose for the first time a special class of noble administrators, “dukes” and “earls” as names for bureaucratic offices; around the thirteen century, this nobility was converted into a distinct legal class; in roughly the same period, there sprang up a caste of stewards and other petty administrators; and over the following centuries, the state would gradually crystallize, centralizing its powers, establishing its monopoly over violence and taxes. The key point about monopoly, from the perspective of gay science, is that it tends to subsume the monopolist himself, who never possesses sole power, but requires ever larger staffs to superintend his realm. The structure tends to become autonomous, to sideline even the sovereign, until there emerges a system without a proper ruler, a system whose head is merely its highest servant. It is at this point, then, that the institutional history tips over into a history of the new subjectivities that these institutions generate, or an ideological history, if you prefer: a history of chivalry, first of all, which is the code by which the old armigerous nobility allowed itself to be christianized; of the pious peace brotherhoods that sprang up during the feudal centuries—sacred vigilantes, ready, in the name of Christ’s concord, to put and end to all that knightly hack-and-slash; of courtesy and everything summed up in the notion of the “civilizing process,” the protocols of conduct—the handkerchiefs and steak knives—that increasingly came to regulate elite bodies. Each of these histories tells a tale of the nobility’s gradual castration, its embourgeoisement or caging. And what we call modernity or bourgeois society is merely the conclusion of this long process, a strange mutation in human affairs by which the upper classes, of all people, came to constrain themselves, to give up the ordinary prerogatives of their power, the joy of rule. Bourgeois society is a place of pervasive unfreedom, the one perverse social order where not even the rulers are free, a society of boundless restriction and self-restraint, the compulsory shame of mutual interdependence.

The word that best encapsulates this historical sea-change is “gentle.” How is it, Nietzsche asks, that the old fighting classes, the pugnatores, metamorphosed into “gentlemen”? How did the nobility, the genteel, come to take as their closest cognates the gentle and the gentile, the tenderhearted and the Christian (with Christians understood here as little more than Hebrew wannabes). Nietzsche’s project, then, is to cut the European nobility free from this crippling constellation—not the really existing nobility, perhaps, but some hypothetical nobility yet to come—to imagine the nobility de-Hebraized, de-Christianized, de-feminized, de-gentrified. And his basic strategy is to reach back behind the long history of the civilizing process—back behind the histories of the state and chivalry and etiquette—so that he can find in early medieval Europe the image of a gloriously raw nobility, a warrior Europe of Ostrogoths and Visigoths, of Franks and marauding Vikings. One hesitates, finally, to call this a medievalism, because that term generally connotes a certain Victorian piety, a cowled churchliness, and Nietzsche’s is a medievalism that fully avows its own most wickedly Gothic qualities, its high terror, its gory sublimity. This point is worth dwelling on, because Nietzsche is typically taken to be a special kind of classicist, the mutant philologist who wants to refashion Europe on the model of pre-Socratic Greece. But Nietzsche’s notion of the pre-Socratic can only be understood as ancient Greece re-described to resemble the early medieval West—a tribal Hellenism of tragic ritual and Homeric warfare. Nietzsche’s historical master trope, the one into which all his other historical mythemes get sutured, is the barbarian; he cycles through the set periods of European history and singles out the barbarian qualities of each—the barbarian Greece of Dionysus, the barbarian Rome of imperialists and slaveholders, the barbarian Renaissance of the Borgias, and so on. One effect of this is to undo the usual distinction between the classical and the Gothic, producing the image of a savage antiquity that largely assimilates the former to the latter. Nietzsche’s philosophy is not a break with nineteenth-century thought but merely a recombination of its most familiar components.

But this recombination does not emerge by sheer will or chance. What makes the perception of savage antiquity possible, at the level of material relations themselves, is the modern reconfiguration of Europe around its horizontal axis, separating the metropolitan North from the now semi-peripheral South. Southern European underdevelopment—the long process by which Italy and the Levant, once the center of the Mediterranean world-system, were relegated to the hinterlands of the Atlantic economy—yields at length new images of the classical world: not a refined and civilized South, but a rude and wild South, a South that will henceforth seem archaic, at least by the standards of Berlin or Liverpool. It is this world-historical shift in capitalism’s geography that allows Nietzsche to run together barbarism, antiquity, and medievalism; and out of this conflation Nietzsche will invent an unusually stark modernity narrative, premised on a divide between our cowering modernity and an undifferentiated pre-modernity, in which there was no antiquity as such. The past, it turns out, has always been creative, innovative, given over to rupture and barbarian transformation. Modernity, then, is the first truly classical age—static, weighed down by restraint and proportion and equipoise—which is to say that it is not modern at all, if by modernity we mean all-that-is-solid-melts-to-air. That modernity, the era of dynamism and splendid transience, belongs to the long-ago. And so the Gothic, when set against an inert, geometrical classicism, will suggest not only the outmoded, not only ruined abbeys and moldering fortresses. It will, in those very glimpses of decay, as also in the busy finials and exalted spires of Gothic Revival architecture, suggest historical vitality—not stagnation or arrest, but historicity itself. The Gay Science is the philosophical high-water mark of this Gothic modernism, the equivalent in thought of a Victorian railway station built to look like a castle or a factory disguised as a basilica.

If you want to figure out what gay science wants from you, then, you have two choices: You can treat gay science as a philosophical argument—the creative vocation of free thought; or you can treat it as a historical allusion—the Gothic art of knightly poets. The vital point, however, is that these accounts correlate, which means that there is really no choosing between those options. It is through philosophical argument that Nietzsche means to effect his medievalist historical revival. If we sign on to the philosophical project—if, that is, we learn to treat knowledge as something other than knowledge, learn to see all thought as creative—then we will help end the tyranny of truth and science and bring into being a “genuinely savage” future. Nietzsche calls upon us to de-epistemologize our modernity, to initiate an un-civilizing process that will destroy science as a separate sphere, with its own practices and institutions: telephone surveys, public schools, government accounting offices. And medieval Europe serves Nietzsche as the model of this non-epistemological society, in which there will be no more knowledge for its own sake. It is impossible to embrace gay science in purely philosophical form; the phrase itself is a permanent memento of the medievalism that underpins its seeming abstraction. If the American Revolution, like the French Revolution after it, was classicism’s uprising, all columned buildings and proud republicans and paintings of Washington-in-toga, then Nietzsche aims to give medieval Europe an insurgency of its own, a Gothic 1776, and The Gay Science will be its Common Sense.

St. Pancras railway station, London

St. Pancras railway station, London

MORE SOON…

A FEW NOTES

-For more on commas and semi-colons, see Adorno’s “Punctuation Marks” in the first volume of his Notes to Literature.

-Herrick’s poetry begins to make sense once you’ve read Christopher Hill’s Society and Puritanism in Pre-Revolutionary England and Leah Marcus’s Politics of Mirth.

-Hardt and Negri’s tag lines all go back to a passage early in Deleuze and Guattari’s Thousand Plateaus: “write with slogans: Make rhizomes, not roots, never plant! Don’t sow, grow offshoots! Don’t be one or multiple, be multiplicities! Run lines, never plot a point!”

-The bit about the Jews comes straight from Nietzsche—see The Gay Science, #136: “the Jews take a pleasure in their divine monarch and the holy which is similar to that which the French nobility took in Louis XIV. This nobility had surrendered all its power and sovereignty and become contemptible.”

-For more on the European nobility, see the classic works of medieval social history: Bloch’s Feudal Society; Duby’s Early Growth of the European Economy; and especially Elias’s Civilizing Process.

-The photograph at the top is Vincent Diamante’s.