Good luck had just stung me

To the race track I did go

She bet on one horse to win

And I bet on another to show

Odds were in my favor

I had him five to one

When that nag came around the track

Sure enough we had won

-Up on Cripple Creek, The Band

Thank god for Bob Dylan. I’m sure that’s something that is said daily, but my reasoning is probably different than most. Instead of being in awe of Dylan for the music he has brought to this world (“Mr. Tambourine Man” is one of my favorites), and the way he has changed rock music, I’m in awe because without him there’s a good chance the Band wouldn’t be a band. Yes, they would have been known for their stint as the Hawks, and as Dylan’s backup band, but we wouldn’t have songs like “The Weight” or “Acadian Driftwood” or “Up on Cripple Creek”.

Soon after leaving Ronnie Hawkins–the musician who initially brought the Band (previously known as the Hawks) together–the Canadian-American band was stung by good luck because they were sought after by Bob Dylan. The Band went on Bob Dylan’s 1965-66 world tour excluding Levon Helm who was at Dylan’s Forest Hills, New York, concert in 1965 where they got booed by the crowd: Helm was quoted saying “I wasn’t made to be booed”. In 1966, though, Helm rejoined the Band and Bob Dylan in West Saugerties, New York, after Dylan got in his famous motorcycle crash. The Band rented a house, well-known as Big Pink, to be closer to Dylan while he was out of the public eye for a little bit. The motorcycle crash ended up having a positive outcome for both Dylan and the Band as they went on to record over 100 tracks together in Big Pink. A number of those tracks went on to be known as The Basement Tapes, arguably some of the best songs written by the two parties.

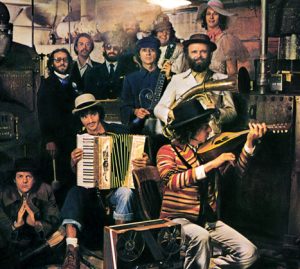

The story of how and why these tapes were made is one that should be an inspiration to all musicians. They created a little studio in the basement of Big Pink, and sang/composed for themselves: not for a crowd, a studio, or for fame. Robbie Robertson reminisced, “We went in with a sense of humor. It was all a goof. We were playing with absolute freedom; we weren’t doing anything we thought anybody else would ever hear, as long as we lived. But what started in that basement, what came out of it—and the Band came out of it, anthems, people holding hands and rocking back and forth all over the world singing ‘I Shall Be Released,’ the distance that all of this went—came out of this little conspiracy, of us amusing ourselves. Killing time” (Old, Weird America). Their way of killing time led to what some critics say was a stylistic transformation for rock music: you can see this transformation in Dylan’s music as well. He went from albums like Highway 61 Revisited to songs that were more rooted in traditional American music like “I Shall be Released”. As for the Band, well, they became the Band with their debut album Music from Big Pink. They obviously did not spend a lot of creative energy on the name of their band, or the name of their first album, but it’s okay because it’s quite obvious that they spent a lot of it on their music.

In 1968, “The Weight”, from Music from Big Pink, hit its peak at #63 in US charts-a deplorable rank as Aretha Franklin’s cover of the song hit #19 in 1969. I use the word deplorable because the Band’s version is much more pleasurable to hear. No offense to Aretha Franklin, she has a great voice, but the best part of the original version is the chorus where you can hear up to three different voices all coming together to pitch the perfect imperfect harmony.

This imperfectness is what makes the band so unique; other bands with multiple lead singers–most notably the Beatles with Lennon, McCartney and the occasional Harrison–harmonize so beautifully as though their voices become one. The Band does the exact opposite by providing a different type of harmony: ragged, throaty, asperous, and broken. Musicians harmonize because it sounds better than individually singing/playing-the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The Band does indeed do this this, but it does it in a way that both the whole and the parts are both equally as good: you’re able to hear the individual voices in the harmony as it goes in and out throughout lines, but you’re able to enjoy the voices together as well. This abnormal harmony is seen in most of their songs: “Acadian Driftwood”, “Atlantic City”, “Up on Cripple Creek”, etc.

The Band was able to create songs that were both meaningful, and meaningless, but both equally gratifying to their audience. Contrary to popular belief, “The Weight” is not meant to be taken as a serious song. Critics have spent years analyzing the song and its biblical references, but Robbie Robertson has said that this song was influenced by the director Luis Bunuel and the characters in his movies. This song was written in Big Pink when they were just fooling around and having fun with music. On the other hand, in 1970, Robertson wrote the song, “The Shape I’m In” which is about the rough spot they were all in after fame started to take its toll on the musicians, especially Richard Manuel. Manuel was an alcoholic in despair which made it hard for the band to keep going as they did before: it took them 4 more years to release a new album, Northern Lights — Southern Cross.

Unlike Music from Big Pink, Northern Lights—Southern Cross, does having a meaningful background behind the name. It has Northern Lights because of the four Canadians in the band: Robbie Robertson, Garth Hudson, Richard Manuel, and Rick Danko. And Southern Cross because of the one southerner, Levon Helm. This album was especially significant because it marked the first time Robertson wrote about his home land in “Acadian Driftwood”. “Acadian Driftwood” is about the banishment of the Acadians during the French and Indian war: something that could resemble Robertson’s early life. His music career prompted him to travel from Toronto to the south, an unknown land: even when he lived in Toronto he didn’t exactly feel like a native because he was of Jewish and Mohawk descent. The history behind this song isn’t exactly something that would amuse pop music listeners, and it didn’t as the song didn’t crack the top 100: a shame because it’s one of the more significant songs written by the Band with some of the best vocals.

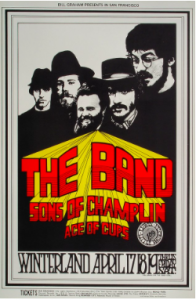

In 1969, Greil Marcus, a well-respected rock critic, praised the band on sticking together: “It’s something else to found a group that lasts. It’s not a matter of “I-Was-There-When,” though that’s part of it; with so many bands falling apart or kicking out members or just calling it quits, The Band has stuck together” (Review). This was something that Marcus loved about the band, but was unfortunately something that did not last: the Band called it quits after a Thanksgiving Day concert in 1976 after 16 years of being together. Although this would have been a fine ending to their career together as most bands eventually come to an end, the aftermath of the Band was not pleasant. After part of the band regrouped in 1983, Manuel hung himself with a belt in his hotel room after a concert in Winter Park, Florida: he had traces of cocaine and alcohol in his body. Levon Helm, the one American in the group, declined an offer to go to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame after the Band was inducted into it because he was not happy with how Robertson took sole credit for songs that were written as a collaborative effort. Danko was found guilty of trying to smuggle heroin into Japan in 1996, and then later passed away at 56 in his home in Woodstock, New York. The band member whose life most closely resembles a perfect ending to a movie is Levon Helm. He returned to his house near Woodstock (where the Band’s career kicked off), after developing throat cancer. He could barely speak, but in order to pay for the mounting debts he was incurring he started hosting Midnight Rambles at his barn. His voice miraculously started to strengthen and, in 2004, he was able to belt out classics from the Band. If I were to write a movie on the Band, I would make it so that the ending to the Band was just as good as the beginning, but that just isn’t the shape they were in.

I’m gonna go down by the water

But I ain’t gonna jump in, no, no

I’ll just be looking for my maker

And I hear that that’s where she’s been? Oh!

Out of nine lives, I spent seven

Now, how in the world do you get to Heaven

Oh, you don’t know the shape I’m in

-The Shape I’m In, The Band