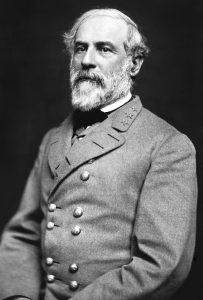

The political climate has become dangerously nasty here in the U.S, and all of that animus came to a head in Charlottesville last August. It doesn’t need much explaining: we all heard about it; we were all outraged by the events. It definitely was a low point in our public discourse. Now, one of the immediate effects of Charlottesville was to bring the issue of statue removal out into the open. The whole Charlottesville fiasco revolved around a statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee, and since a person was killed over that monument, statues must be a pretty big deal. And in fact, they are a big deal for our culture, because they are supposed to represent the ideals that we respect, revere, and hold dear. So naturally, when a group feels that a monument does not reflect their values, they will attempt to replace it or rid themselves of it completely. While on the other hand, people will vigorously defend a monument when they feel it’s worthy. But how exactly does a person make a decision upon the acceptability of something like a monument?

Well, the way I conceive of it, it all comes down to two different scenarios. Either a person will rely heavily upon pure ideology and emotions, or a person will rely primarily upon logical thinking based on facts. (In the context of this argument, I’m taking ideology to be the ideas and frames of thought that we fall back upon subconsciously. Essentially our inherent intellectual biases.) Now, if we look at which is the dominant method, it would be the former because social and cultural life are “governed by ideologies.” This occurs largely because in order to guide our choices, it’s convenient and comfortable for us to pick from the things we know. Especially in extremely emotional situations like Charlottesville, our instincts grab for the quickest reaction from the framework of our mind – our ideologies. Now, this becomes a problem when we consider the philosophical claim that ideologies operate by thinking about things as though they don’t have histories. For example, when we go and buy a shirt we never stop to consider its (likely) history of being made in a sweat shop in Vietnam or Honduras. It just does not cross our minds. Similarly, the statue controversy is also evidence for this claim.

To see why this is the case, consider that in the aftermath of Charlottesville, we saw a swift movement by many city councils across the country to remove Confederate monuments in their towns. One personal instance of this is my hometown in Montana, where a Confederate fountain was promptly removed following Charlottesville. But what was also promptly removed was the public debate concerning the removal of the fountain that had been going on for years prior, since the Ferguson riots. In an instant, a logical debate about the merits and drawbacks of the fountain evaporated and was replaced by a view of it as simply a racist object – no history, no facts, just racist. Similarly in Durham, North Carolina, a statue of a generic Confederate soldier was torn down by protesters. And then for good measure, the protesters took turns stomping on the bust to really teach it a lesson. Obviously these peoples’ actions were dictated solely by their ideologies. What I mean is that most would not classify stamping down on rocks as logical behavior. Really, all these people knew was that the item they were dealing with was racist and that it must go; thus, no thought was put into the history and context of the object. In effect, they only took in a portion of the statue’s qualities because their political ideologies took a front seat in their thought processes.![]()

Now you – the reader – are probably thinking that in the case of these statues, it’s a good thing that people are acting on their ideologies because Confederate monuments really are racist and should have no place in America. Well, you would be correct….to a point. To see why, consider that if ideology does shutter us from seeing the full picture of an object, and if we are relying on ideology in our assessment of statues, we are not getting the full picture of this problem. Therefore, to illustrate how we can get a wholesome analysis of a statue or historical figure, I will outline with two examples how we can use a logical and fact-based approach to come to a more informed decision.

First we will go to Memphis, Tennessee where there’s a statue of a Confederate general named Nathan Bedford Forrest. By any standards, Forrest was a bad dude. According to History.com, before the Civil War, he owned several plantations and many slaves. He also amassed a small fortune in the horrendous trading of slaves. During the War, Forrest became a vicious cavalry commander. In 1864, at the Battle of Fort Pillow, Forrest slaughtered hundreds of Union soldiers – many of them free blacks – after they had surrendered. After the War, Forrest founded the Ku Klux Klan to terrorize freedmen and ensure the survival of the Southern tradition, becoming the group’s first “Grand-wizard” (History.com). Given this information, we can make a logically informed decision about the kind of man Forrest was, and upon whether we should accept a monument in his honor to stand in a public space. And with these facts, any fair-minded individual would deem Forrest a traitor, killer, terrorist, racist, etc. and would find it repulsive to honor him publicly in any way. Really, all one needs to consider is the scenario where an African-American from Memphis has to walk by a statue of the founder of the KKK to go to the park, and it’s obvious that the statue must go. The only conceivable place where a Forrest statue would be warranted is at a museum or historical site. For example, at the site of the Battle of Ft. Pillow, a statue of Forrest complete with ample descriptions of his life would be tolerable for the purpose of preserving history, so that the world might not suffer from another Nathan Bedford Forrest.

For the second example, let’s get back to Robert E. Lee and examine him more closely. First of all, historical documents show that Lee was very torn over the issue of slavery. Around 1856 he penned a letter to his wife that included passages such as: “In this enlightened age… slavery as an institution is a moral & political evil in any Country.” But also: “I think it however a greater evil to the white than to the black race, & while my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more strong for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially & physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things” (Blount). So Lee exhibits the very common racist idea of the time that blacks need “instruction as a race,” but he also finds slavery to be evil and a drag on the morals of the nation. Also, in a twisted way he hoped that slavery would “prepare & lead [African-Americans] to better things.” The ambiguousness of this thought is astonishing because he seems to want blacks to have a better life, but also finds it acceptable to have them enslaved and oppressed. So it would appear based on this that Lee had a higher moral standard for his time and place, especially compared to men like Forrest. But this still does not subtract from his debased racial ideology. Turning to the Civil War, Lee was actually set to be on the Union side. Educated at West Point, Lee served in the U.S. Army for over 30 years; but when his home state of Virginia joined the Confederacy, he of course chose to side with his family roots (and the institution of slavery) over his country. This traitorous decision put him on the wrong side of history to be sure. But after surrendering to General U.S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse in 1865, Lee was a proponent of reconciliation and accepted the abolition of slavery. He did not institute a reign of terror such as Forrest did by founding the KKK; rather, he strove for a peaceful resolution. His racist ideals did not improve however, as he believed that blacks were not intelligent enough to vote after they were freed (Blount). So overall, there is more to Robert E. Lee than one might initially think. Despite his ardent racism, Lee had some honorable qualities and wanted the African race to be better off – albeit in a sick and cruel way.

Back to the statue conundrum, we are now in a better position to decide what should become of Lee monuments. This one isn’t as easy as the Forrest situation, so it should come down to context and the citizens who own the monument space. If a public square has a statue of Lee on horseback bedazzled in Confederate regalia complete with battle flags and the like, the people of that residence have all the right to say: “you know what? This Robert E. Lee was very hostile to African-Americans and we feel that this statue doesn’t represent our values.” Another possibility could be to keep a Lee statue but have a plaque describing Lee’s history and his good and bad qualities. And then maybe at a place like Washington & Lee University, they might decide that a statue of Lee might be desirable because he was president of the college and that he was an honorable man in an academic context. Truly, any course of action is sufficient as long as it’s not subject to ideological authoritarianism and is made with full knowledge of the facts.

After considering these two examples, we see that both Confederate generals were more than just racist. Forrest was a racist, but also a brutal killer and tyrant. Lee was a racist, but also exhibited noble thoughts and actions towards blacks and his Northern opponents – a moral step above most white Southerners of his time. (Remember, this is not glorifying Lee in any way; it’s simply a logical observation based upon historical evidence.) When we obtain these more holistic pictures of historical figures we are no longer relying on raw emotions and blind ideology to inform our decisions, but rather logical and factual thinking are guiding us. Some people may not agree that this approach is preferable, but hopefully will see that it does have merit in that it relies on common sense and hard evidence.

The main issue with the ideological approach to the statues, – deeming them racist – although valid, is that it’s severely insufficient to simply discredit a historical figure as a racist. For in reality, we could classify almost every white American in the 18th and 19th centuries as racist from our 21st century perspective. This includes Abe Lincoln who would have been happy to preserve slavery in order to preserve the Union (fortunately that was not the case). In other words, there are two ways we can look at this issue: (1) we can classify every person that came before us as bad, or (2) we can acknowledge that those that came before us shared a bad quality and then differentiate the kind of people they were in a different way – in the context of their time period. Because really, Americans 100 years in the future will look down upon us for things that we do. Maybe it will be for fidget spinners, or for Youtube families – maybe even for dank memes. Either way, our progeny will look down on us just as we do our forebears. Anyways, if we refuse to make distinctions about historical people and want to tear down statues simply because they’re “racist,” we can knock down every statue.

But this, in all actuality, is the threat that our country is dealing with – the threat essentially of cultural cleansing. The Confederate statue thing is just the tip of the iceberg. Although we did talk about how there are other options for the Confederate monuments, most Americans recognize that those statues represent treason and oppression and that their time is up. But those that hate this country are setting their sights higher. The Founding Fathers and even the Constitution may soon be on the chopping block, for our Founders were racist, and the Constitution contains extremely racist and oppressive language (3/5’s Compromise). Just last month, the school district of Dallas, Texas announced they will look into changing the names of schools named after figures such as Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison. How will these people make this decision? And how far will this go- how far are we willing to let this go? We are on a slippery slope. We can either kick down our legs and stop in the right place, or slide right down to the bottom.

Citations

History.com Staff. “Nathan Bedford Forrest.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 2009, www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/nathan-bedford-forrest.

Blount, Roy. “Making Sense of Robert E. Lee.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 July 2003, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/making-sense-of-robert-e-lee-85017563/.