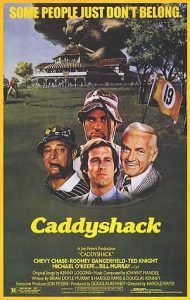

On the surface, Harold Ramis’s film Caddyshack appears to be an irreverent summer comedy. The cast includes mostly stand-up comedians, the jokes are juvenile, and it lacks a cohesive plot. It’s funny, most viewers and reviewers agree, but not anything more than that. Gene Siskel, in his review of the movie in the Chicago Tribune, calls it a “most disposable motion picture, the kind of film that drive-ins were designed to play” (Siskel). Maybe, though, Caddyshack is more than just a stupid comedy. Critical thinkers have argued that all stories—including comedies—present a real social crisis and proceed to offer a solution to that conflict. What real social conflict, then, does Caddyshack present? What solution does it offer? Or does a story not necessarily have to do these two things, and Caddyshack really is nothing more than a dumb comedy

To think more carefully about this,we must focus not on the comedic aspect of the movie but instead on its characters and plot. The film centers on Bushwood, an exclusive country club. A variety of characters populate the story: Danny, a caddy, Maggie, his girlfriend, Ty, a relatively young member, Carl, the hapless groundskeeper, and Lacey, an attractive young woman. However, what drives the story is the conflict between the two most important characters: Judge Smails, a proper, long-time club member and self-proclaimed gentleman, and Al Czervik, an brazen, obnoxious nouveau-riche newcomer to the club. The Judge resents any change to the atmosphere and decorum of his beloved club, and Czervik’s boisterous personality and lewd jokes certainly threaten to disrupt that atmosphere. To anyone who reflects on the film even briefly, it becomes clear that the conflict between these two represents a conflict between the traditional, conservative values of the judge and the progressivism of Czervik. So, upon even a cursory inspection of the plot, the film shows itself to be more than just an irreverent comedy. We need to dive deeper into the film, however, to explore the real social conflict it presents to us. What traditional values, exactly, does the Judge represent? What does Czervik represent?

To answer these questions, we must focus on another aspect of the film: its fascination with sex. Three distinct sexual encounters take place on screen—Danny and Maggie, Ty and Lacey, and Danny and Lacy—but more than that, sex is constantly on our minds as viewers. The movie bombards us with sexual metaphors and imagery to ensure it. Carl lusts after the female golfers while stroking a golf ball-cleaning machine. He later drags a hose along the golf course with the end sticking out between his legs. Danny—and all of the other young men—lust after Lacey. The very act of golfing—a bunch of men swinging sticks—is just another sexual metaphor. The movie never lets us forget that its true focus is sex.

So let’s bring these two ideas together and see if that makes sense. Let’s suppose that Judge Smails represents traditional sexual values, and that Czervik represents sexual progressivism, and see what kinds of specific evidence we can come up with to support that theory.

First, however, we must determine exactly what “traditional” and “progressive” sexual values were at the time. In the 1960s and 70s, young baby boomers carried out what has been called a sexual revolution, attempting to change traditional values towards “women’s sexuality, homosexuality, and freedom of sexual expression” (Escoffier, 1). One of the principle ideas they fought for was the end of sexual repression, which they believed “distorted psychological development and led to authoritarian behavior” (Escoffier, 2). Thus, sexual repression—not talking about sex and not having sex—constitutes a traditional value while the fight to end sexual repression is a progressive one. So let’s see if Judge Smails represents sexual repression and Czervik the fight against it.

In the film, Judge Smails does focus deliberately on repressing sexuality and any mention of sex at all. During the dinner scene at the club, he balks at Czervik’s sexual jokes, aghast that anyone would say such a thing in civilized, proper society. To a gentleman like Smails, sexuality is not something to be talked about; it is something to be hidden away, never discussed publicly: repressed. Later, when the Judge sees Danny in bed with his niece Lacey, he fills with rage at the display of pre-marital sex, violently attacking Danny as he flees. With this action, the Judge reveals his hatred for sexuality and his desire for sexual repression; why else would he become so enraged at Danny?

The Judge’s focus on sexual repression also manifests itself metaphorically with the gopher. Judge Smails assigns Carl the task of killing a gopher that has invaded the course. Through Carl, Judge Smails literally tries to stamp out a “varmint” that has invaded his proper country club, just as he tries to stamp out any mention of sex from proper conversation and sexuality itself. It is also worth noting that this gopher came over from the property of one of Czervik’s construction sites; Judge Smails is trying to stamp out the sexual permissiveness of Czervik.

For his part, Czervik certainly represents a more permissive sexual culture, one in which sexuality is not something to be repressed, but instead celebrated. He cracks sexual jokes regularly, talking about sex in a way the conservative Judge Smails refuses to. With the final line of the film, Czervik proclaims “We’re all going to get laid!” This statement contrasts noticeably with the Judge’s anger over Danny and Lacey, demonstrating Czervik’s openness to sexuality where the Judge has none.

So the film does present us with a real social conflict—the conflict between sexual repression and liberty. What, then, is the solution that it offers? Just by looking at which of the characters is more likeable, that solution is not obvious. Judge Smails is conceited and mean, while Czervik is brash and obnoxious. Neither one presents a particularly appealing model to emulate. In the final showdown between the two—a golf match with $80,000 riding on it—Czervik defeats the Judge, potentially indicating the film’s preference for Czervik’s sexual liberty, but his victory does not alter his obnoxious arrogance.

Instead of using Czervik to provide us the ultimate embodiment of sexual liberty, however, the film gives us Ty and Danny, both significantly more likeable than either Czervik or Judge Smails. Those two side with Czervik in his golf match against Judge Smails—they side with the sexually liberating man rather than the repressive one. In the end, it is actually the team of Danny and Ty who win the match on Czervik’s behalf—not Czervik himself. The Judge’s metaphorical sexual repression inadvertently causes their victory; Carl sets off a series of explosions in an effort to destroy the gopher that cause Danny’s final putt to drop into the hole and destroy golf course. By trying to repress sexuality, Judge Smails actually provides for the victory of sexual liberation and the destruction of his traditional club. Thus, as the solution to the conflict, the filmmakers present the rejection of sexual repression and the acceptance of sexual liberty.

To recap: an inane comedy made a bold cultural and political statement without you consciously realizing it. The film, however, exerts a subtle influence over its viewers, compelling them to accept its views as they root for the Danny and Ty to triumph over the Judge.

This is where the historical context for the film becomes important. The sexual revolution happened largely in the 1960s and 70s, yet Caddyshack was not released until 1980. So was the film merely affirming people’s new views about sexuality, or was it trying to change the opinions of those who still held out for traditional beliefs? I would suggest that it was trying to change the views of those still hesitant about the new ideals. The film revolves around golf, a famously traditional and conservative sport played predominantly by older men, and thus could have attracted an older, more conservative audience, an audience that had not quite readily accepted these new values. It then proceeded to demonstrate to these people how they did not want to be like Judge Smails and allowed them to revel in the fact that they could change their views on sexuality without becoming Czervik by demonstrating that they could instead becoming Ty. Ty still represents these new values, yet he is much more acceptable to these audiences than is the obnoxious Czervik. In this way Caddyshack, a stupid comedy, could have changed the views of its audience on a major cultural issue without them necessarily even realizing it.

Works Cited

Caddyshack. Directed by Harold Ramis, Warner Bros., 1980. Amazon, amazon.com. Accessed 14 Oct. 2017.

Escoffier, Jeffrey. “The Sexual Revolution, 1960-1980.” glbtq. glbtq Archives, 2004, www.glbtqarchive.com. Accessed 14 Oct. 2017.

Siskel, Gene. “‘Caddyshack’ right on course as a low-budget laugher.” Chicago Tribune [Chicago], 29 July 1980, chicagotribune.com. Accessed 14 Oct. 2017.