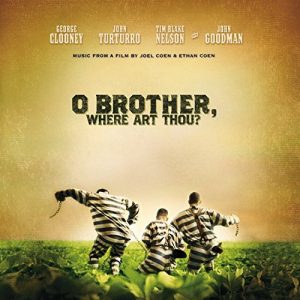

As long as popular culture has existed, so have those who seek alternatives to popular culture. These theorists tend to worry about the mass-produced culture that comes from an elite minority. In the search for an alternative, traditional American music has come to hold an important place in the world of cultural theory. It’s an exciting prospect; any one of us can become culturally enlightened just by buying some bluegrass records and maybe making a trip to a music festival in the Appalachians. Unfortunately, that those sort of supposed engagement miss the mark, because folk music is not always what it seems to be, and there are a lot of conflicting perceptions and misperceptions. The soundtrack to the Coen Brothers film O Brother Where Art Thou? thus comes into focus as one of the more notable and recent segments of a long line of thought about traditional American music.

The quest for an ideal form of culture starts with Matthew Arnold, who agues that Great Books are the form of culture that make people better and improve society.[1] Drawing on the work of ballad-hunter Cecil Sharp, F.R. Leavis proposes Appalachian society as an example of people who, mostly outside the evil influence of the Industrial Revolution, are masters of the “art of social living”[2] without needing literature to achieve perfection. But for those not in the Appalachian region, Leavis says, preindustrial literature is the only way to achieve perfection. Raymond Williams dismisses Leavis’s emphasis on literature as “an emphasis on minority culture” but extends Leavis’s praise of Appalachian society to all working working-class people around the world.[3] As he continues to write that “culture is ordinary,”[4] Williams means that the it is not studios in Hollywood, the publishers in New York, or the record labels in Los Angeles who create culture, but instead the farmer in the rural South and the worker in Appalachia who create shared meanings and values. Relating back to Arnold, Williams believes that culture in the correct form builds a better society, and that form is a democratic culture in which “all of its members are engaged in creating in the act of living.”[5] This is where traditional American music comes in, as the most obvious form of democratic culture. The explicit link between democracy and folk music comes not from Williams but from a rather unlikely source: The Communist Party.

The political use of folk music started in Russia with Lenin using Russian folk music to energize what became the Communist Party. As the party moved to America, its leaders, who were very much out of touch with the working class base of the party, needed a strong cultural symbol to the mobilize and unite the party.[6] The party deemed folk music to be the most American form of music and therefore the best way to link American democracy and communist ideals. The lack of commercialization in folk music was also beneficial for a party opposed to capitalism. As the Red Scare and McCarthyism came into effect, the Communist Party lost any hope of being a part of American politics, but the music had created a subculture that took off after the Cold War ended. For example, The Weavers, a group that started as a musical act for the party, toned down their liberal views and got into the commercial scene after backlash against groups with Communist affiliation had died down.[7]

It is worth pausing here to discuss the definition and authenticity of folk music. This is a discussion not a declaration because a standard definition does not exist and authenticity is impossible to determine. The most basic method is to define folk music by what it is not, and that is popular music. By this definition, folk music has no clear title or writer and also no professional musicians. The International Folk Music Council in 1954 adopted the standard of oral transmittance, with emphasis on the changes that occur as a part of this process.[8] The council accepted that the music could be the product of an individual as long as oral tradition led to or resulted from the product. Ironically, the Council then changed its name to the International Council for Traditional Music, in part because of the difficulty of defining “folk music.” For lack of a better term, I will use “folk music” to refer to traditional music from the Appalachian and Southern regions of the United States. As folk music relates to Williams’s ideas, the most important factor is that the music originates from ordinary people, not the elite minority. Authenticity of recorded folk music becomes tricky under the oral transmittance definition because once it is recorded, it has been forced into a final form. For this reason, autochthonous—meaning arising naturally from the native people—is the best standard in that it focuses on organic creation of music by the people.

It would seem, based on Leavis, Williams, and the Communist Party, that the way to promote a democratic culture is to let working-class people share their culture so it can take over the nation. By extension, it would seem that the O Brother Where Art Thou soundtrack is the perfect way to do so, and many people believed that it accomplished this. The reviews describe the soundtrack in a similar fashion to the way the Communist Party had described folk music 40 years ago, reflecting the romanticized notion that the Appalachian sound is the authentic American sound. One critic praised the album’s ability to “accurately reproduce… country music’s roots,”[9] while another gave the soundtrack credit for the “power and authenticity” of the film itself.[10] One review even attempted to link Appalachian music to preindustrial England by noting the use of banjos on the album and then erroneously claiming that the instrument has British origins when it is in fact African.[11] This disregard of African American influences on Appalachian music is a very common misconception, according to Appalachian Studies professor Ted Olson.[12] The fact that the album was very popular despite receiving virtually no radio airplay helped fuel the narrative—one that newspapers loved to cover—of a class conflict in which ordinary people flocked to this music despite, or maybe even because, the radio executives tried to keep it away from them.

What these reactions fail to perceive is that the music they are describing is not the folk music of the left-wing politics. When folk singers were performing traditional folk songs at Communist rallies, the music was still, more or less, in the hands of the people. It’s hard to know exactly what Williams would say about such use of traditional folk culture, but based on his connection between working class culture and democratic socialism, it is reasonable to infer that the use would fall in line with his ideas. Once the folk revival came around, the music was no longer rooted in masses in the same way, with professional singers and commercial recording becoming the norm.

The even greater fallacy of these reactions is the idealized notion of Appalachian culture that goes back to Leavis. In his book All That Is Native and Fine, David E. Whisnant argues that cultural missionaries—a group that includes Arnold and Leavis—have painted a romanticized picture of Appalachia for the purpose of “systematic cultural intervention,” which means using and changing parts of a culture, usually for monetary gain.[13] Whisnant calls into question Leavis’s idea of uncorrupted culture in Appalachia by criticizing ballad hunters—a key source in Leavis’s argument—for promoting the “ironies and confusions that have characterized most organized cultural work in the mountains.”[14] Another example is the White Top Folk Festival, whose misguided display of Appalachian music resembles the approach of O Brother. The festival, held in Virginia, was meant to highlight local music, but the organizers decided to make it a competition, and as a result, many Appalachian musicians performed songs that were handed to them minutes before they went on stage.[15] With this point, Whisnant supports the standard of oral transmittance and observes that Appalachian people were singing what someone thought was Appalachian music is clearly not a true representation of that culture. The perception of an Appalachian society where people make music all day stands in contrast to the harsh reality of a neglected population that works in coal mines.

The album’s success is unusual in the music world but falls into the broader theme of Appalachian culture becoming popular. In an article from the same time, Appalachian novelist Lee Smith calls attention to successful novels and films that highlight Appalachia.[16] In a more recent example, the video game BioShock Infinite won the award for Best Song in a Game with a new recording of “Will the Circle Be Unbroken.”[17] Smith says that “mainstream American culture is becoming “Appalachianized,””[18] but a more accurate statement would be that Appalachian culture is being Americanized, and by Americanized I mean commercialized. T Bone Burnett, the producer of the O Brother soundtrack, engages in cultural intervention as he successfully commercializes the music. Writing for Rolling Stone, music critic Robert Christgau draws contrast between O Brother, where songs are “concocted in the studio,” and Inside Llewyn Davis, another Coen brothers film, where Burnett has the actors performing on set.[19] While actors are obviously not common people, one could argue that in this case, they are closer to Williams’s idea of the common person than are the professional bluegrass and folk singers on O Brother.

The creators of the album also have misconceptions in regard to its so-called authenticity. Ethan Coen, one of the film’s creators, attributes the album’s success to its evocation of an era “when music was a part of every day [sic] life and not something performed by celebrities.”[20] What is ironic is that the songs on the soundtrack are performed by celebrities of the folk music world. Dan Tyminski, who provided the Grammy-winning vocals in “Man of Constant Sorrow,” has vaguely Appalachian roots but now has “one of the most recognizable voices in acoustic music,”[21] which is to say, he is a celebrity. After being featured on EDM artist Avicii’s hit song “Hey Brother,” one would be hard pressed to call him a “common” person.

The alternative to the O Brother soundtrack is an album like American Epic, a soundtrack that uses original recordings of similar songs. These recordings come from the 1920s when ethnomusicologists like Alan Lomax traveled Appalachia and the south, making recordings of rural and working class people who knew songs from the oral tradition.[22] The music in these recordings is autochthonous because it originated in oral tradition and is being performed by ordinary people. The recording technicians called it “catching lightning in a bottle,” which reflected both the one-take method mandated by the equipment and the nature of the music.[23] Just as lightning is a powerful force of nature, folk music is a force of the democratic culture. By using commercial recording methods—multiple takes, editing—O Brother fails to achieve the characteristics of live recordings. That American Epic has received only moderate attention and sales in the six months it has been out while O Brother had gone platinum by that time would suggest that people actually do want to hear celebrities or professionals performing.

It is also important to distinguish music that comes from Appalachian culture and music that is influenced by Appalachian culture. Gillian Welch, who performs on the O Brother soundtrack, released two albums of her own around the same time. Her use of Appalachian music styles created controversy as critics thought Welch, who was essentially born into the music industry, had no credibility in the realm of folk music. Music writer Tom Piazza argues that this criticism is unfounded because “Gillian Welch is not playing, or claiming to play, “traditional music,” any more than Bob Dylan was.”[24] When singing her own songs influenced by Appalachian music, Welch avoids the cultural intervention in which she participates in O Brother. From Piazza’s argument, one can also make a distinction in intention between O Brother—modern recordings of traditional songs—and the folk revival—modern music in the traditional style. The folk music used by the Communist Party falls somewhere between these two, with groups like the Almanac Singers performing both folk standards and their own folk-influenced creations.

If we are to believe Leavis’s assessment of the problem, then we are facing the end of Western civilization due to the industrialization of society and promoting democratic culture is of the utmost importance. As we have seen, projects like O Brother fail to achieve democracy despite popular reaction, but there is still a chance for other forms of culture to blossom. Dissemination of original content, like American Epic, is a possible solution, but it needs an update. Perhaps the answer is more projects of recording technicians traveling the mountains and the South collecting recordings in the spirit of Alan Lomax. Or maybe schools should teach all students to square dance. If we take one lesson from the songs of O Brother, it is that, in the pursuit of a democratic culture, we must “keep on the sunny side.”

[1]. Matthew Arnold, Culture and Anarchy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 5-16.

[2]. F.R. Leavis, “Literature in Society,” in The Common Pursuit (London: Faber and Faber, 2011), 190-191.

[3]. Raymond Williams, “The Idea of a Common Culture,” in Raymond Williams on Culture & Society: Essential Writings (London: Sage, 2014), 34.

[4]. Raymond Williams, “Culture is Ordinary,” in Resources of Hope: Culture, Democracy, Socialism (London: Verso, 2007), 4-7.

[5]. Williams, “The Idea of a Common Culture,” 34.

[6]. R. Serge Denisoff, Great Day Coming: Folk Music and the American Left (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1971).

[7]. Richard A. Reuss, American Folk Music and Left-Wing Politics, 1927-1957 (Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, 2000).

[8]. James R. Cowdery, “Kategorie or Wertidee? The early years of the International Folk Music Council,” in Music’s Intellectual History (New York: Répertoire International de la Littérature Musicale), 808-811.

[9]. Jim Caligiuri, “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” The Austin Chronicle, January 19, 2001, accessed November 14, 2017, https://www.austinchronicle.com/music/2001-01-19/80243/.

[10]. Evan Cater, “O Brother, Where Art Thou? [Original Soundtrack],” AllMusic, 2001, accessed November 14, 2017, https://www.allmusic.com/album/o-brother-where-art-thou-original-soundtrack-mw0000106868.

[11]. Ted Olson and Ajay Kalra, “Appalachian Music: Examining Popular Assumptions,” in A Handbook to Appalachia: An Introduction to the Region (University of Tennessee Press, 2006), 164-165.

[12]. Ibid.

[13]. David E. Whisnant, All That is Native & Fine: The Politics of Culture in an American Region (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 13.

[14]. Ibid

[15]. Ibid., 183-261

[16]. Lee Smith, “Mountain Music’s Moment in the Sun,” The Washington Post, August 12, 2001, Final Edition ed., Sunday Arts, G01 sec.

[17]. Elton Jones, “VGX 2013: The Full List of Video Game Award Winners,” Heavy.com, December 07, 2013, accessed November 14, 2017, http://heavy.com/games/2013/12/vgx-2013-the-full-list-of-video-game-award-winners/.

[18]. Smith, “Mountain Music’s Moment in the Sun”

[19]. Robert Christgau, “The Lost World of ‘Llewyn Davis’: Christgau on the Coen Brothers,” Rolling Stone, December 4, 2013, accessed November 14, 2017, https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/news/the-lost-world-of-llewyn-davis-christgau-on-the-coen-brothers-20131204.

[20]. BBC News Online, “O Brother, Why Art Thou So Popular?” BBC, February 28, 2002, accessed November 14, 2017, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/1845962.stm.

[21]. Jewly Hight, writer, “Dan Tyminski On Mixing Electronic Dance And ‘Southern Gothic’,” in All Things Considered, transcript, National Public Radio, October 19, 2017.

[22]. Legacy Recordings, “American Epic: The Collection & The Soundtrack Out May 12th,” news release, April 28, 2017, Legacy Recordings, accessed November 14, 2017, https://legacyrecordings.com/2017/04/28/american-epic-collection-american-epic-soundtrack-may-12th/.

[23]. Ibid.

[24]. Tom Piazza, “Trust the Song,” in Da Capo Best Music Writing 2000 (Boston: Da Capo Press), 301.