Can a movie be a great work or art, or does its format prevent it from reaching the same heights as great works of literature? Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind is a movie that confronts an issue most will face in their lives, the excruciating process of separating with someone who previously completed you. Eternal Sunshine shows the introspective viewer the rewards yielded from confronting your past, and the costs of blocking your memories. Eternal Sunshine accuses apathy as the ultimate obstacle for human happiness. It is an obstacle that disguises itself in short-term bliss, but produces long-term suffering. Eternal Sunshine critiques apathy through its protagonist Joel Barish, and side character Mary Svevo. Each of these characters deals with their painful separations in the same way. They choose to permanently erase their partners from their memories. This act, literal in the movie, represents the process most individuals undergo after a relationship: shredding pictures, treating their old partner as strangers on the street, and pushing down memories. The difference between the characters in Eternal Sunshine and the ordinary individual, is that they realize their happiness won’t come by forgetting what they once had, but by reflecting on it. From all these valuable transformations of self Eternal Sunshine exemplifies, it proves itself to be ‘great work of art’. Eternal Sunshine provides a shining example that movies can match great works of literature. Eternal Sunshine takes advantage of similar elements used in writing, such as dialogue and symbolism, but it also incorporates elements from its own media, such as music, surrealist scene transitions, lighting, and costuming to reinforce its message. But, it is mostly through Eternal Sunshine’s characters can the average person can hope to overcome the temptation blissful ignorance has to offer, and see that they live their lives to happier more fulfilled ends.

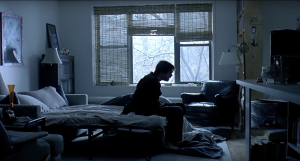

A good place to start is the beginning. Relatable, working man protagonist Joel Barish, wakes up in his barren apartment. We can immediately tell Joel isn’t in a happy man, for the audience looks at Joel through an aggressively blue filter. Slow, lonesome piano music accompanies him out the door to his car, which has been badly scraped. Joel only groans, sticks a passive aggressive “Thank you!” note on the car next to his, and then drives off to work. Joel then begins his internal monologue. The tone of his voice drips with sadness as he reads from his diary entry. It’s Valentines day “a holiday invented by greeting card companies to make people feel like crap” (Eternal Sunshine). But Joel makes a bold move; he ditches work and takes a train out to the beach where he begins to cure his sadness.

Already from this first scene Eternal Sunshine exemplifies the movie medium and sets its tone to be anti-industrial. Along with the blue filter, the objects in the first scene are overwhelmingly of a cool hue. In addition, the viewer is hit by the bluesy piano backdrop, and then Joel’s sad, sad voice weeps out of the speakers. Eternal Sunshine is taking advantage of senses literature just can’t hope to stimulate. Through the auditory and visual interplay of this dismal cinematography, the audience feels depressed with Joel. The color blue and the slow music have strong cultural associations with feelings of sadness. These associations subconsciously enter the viewers thoughts and feelings. Joel’s voice then enters their mind, triggering them to empathize with him, and to feel his sadness alongside him. This raises the stakes for the movie, for Joel’s quest for happiness is no longer his own, but also the viewers. Joel’s eventual transformation into a happier human has become more potent, for it is shared with the viewer. Thus, Eternal Sunshine proves that it can insert its audience into its characters as well as any classic piece of literature. Furthermore, Joel’s flight from work takes Eternal Sunshine away from the destructive philosophies of popular culture. These philosophies prescribe hard work, the latest Ford F-150, and addictive burgers as the key to human happiness. A setting where the path to happiness is found through the explorative introspection, and not through distractions and indulgencies is the foundation for any great work of art hoping to help our humanity.

The destination of Joel’s great escape is the beach. He walks alone except for the sad blue filter and piano music which accompany him. He eventually sees Clementine on the beach staring into the ocean, but doesn’t seem to recognize her. She’s costumed in a bright orange hoodie, a color that contrasts the overall cool hues of the Eternal Sunshine has presented so far. The orange hoodie acts almost like a beacon, for it provides an early hint to the audience of where Joel’s understanding of his happiness might be found. These visual cues pop up to the audience again and again throughout the beginning scenes. Joel leaves the beach, and enters the restaurant leaving behind the sad music, but taking with him Clementine. He continues to the train stop, and with that stops his depressing inner monologue, but follows him again is Clementine. Now, Joel finds himself on the train, and the audience finds the blue filter no longer present. He draws a sketch of the train car, which would be otherwise colorless, if he hadn’t markered in the fluorescent orange hoodie on Clementine, who sits a few seats down. Then Clementine hops over to Joel and in comes a playful brass section. Eternal Sunshine uses cinematic elements to draw the audience’s feelings gradually from a state of sadness to happiness. From this sensory guide, the audience is able to get a brief glimpse of the path to happiness. But, it takes Eternal Sunshine’s uses dialogue and its character transformations to reinforce this guide.

Joel and Clementine exit into the rainy streets of Montauk New York, take shelter in Clementine’s apartment, and begin to talk. They immediately engage in a dialogue exploring the how they live their lives.

JOEL: My Life isn’t that interesting. I go to work. I come home. I don’t know what to say. You should read my journal… I mean, it’s just blank

CELMENTINE: Really? Does that make you sad? Anxious? I’m always anxious I’m not living my life to the fullest. (Eternal Sunshine)

Already the movie is criticizing apathy. Clementine is constantly thinking, and considering how to make her life better, while Joel is just consumed in the stresses of work, and would rather live a distracted life than a fulfilled one. Eternal Sunshine shows the viewer Clementine is the happier of the two. When she talks about herself she is confident in her qualities. In contrast, when Joel talks about himself he doesn’t even know what to talk about. He barely even knows himself. A short while after this exchange Joel excuses himself saying “I have to get up so early tomorrow”. But Joel doesn’t leave without Clementine’s number, and soon after returning to his desolate, depressing apartment he realizes what he has to do. He calls Clementine back. They stay up all night, travelling down to the frozen Charles River, and Joel’s sadness begins to break away. By forgetting his obligation to work, he’s had one of the happiest nights of his life, and met a woman who might help him out of his sadness. From all this, the stage has been set for the real revelations and the real transformations to occur.

From Joel’s extraordinary first date the movie dramatically cuts to him weeping while driving. The steady melancholy bass from “Everybody’s Got to Learn Sometime” by Beck is playing on cassette through the car radio, and the blue filter is turned back on. Joel chucks the cassette tape out the car window, and then his tears stop. This symbolic act shows to the audience the frame of mind Joel’s in. He’s not ready to learn this time; he’d rather reject the painful memories of his relationship then take the time to go through the sorrowful, yet self-developing reflection process. This is a common human flaw, choosing to forget rather than to reflect. But Joel’s forgetfulness reaches what the common person could only possibly dream of. His apathetic condition is exacerbated by the discovery of Lacuna inc., a company offering to erase any sad or traumatic memories from a person’s mind to give them the chance to “move on”. Through this science fiction aspect of the film, Joel is able to take the extra step most people wish they could make. He’s able to totally forget is past, and supposedly get a “fresh start”. But, over the course of the movie Joel’s mindset will change, and act as an example for the viewer that this is not the right course of action.

Eternal Sunshine is best able to change its audience’s mentality through Joel transformation. He enters the mind-erase procedure determined become blissfully ignorant towards his past. The procedure begins with Joel emptying out his apartment of everything that vaguely reminds him of Clementine. The result is the apartment is left barren, and devoid of all personality. One character comments: “This place is a dump… well not a dump, just sort of plain, uninspired” (Eternal Sunshine). Joel had been with Clementine so long, and so intimately that his person, his sense of self, had become entwined in hers. In forgetting her, he forgets a part of himself. This gives the audience a peak into the costs of the procedure. Even while Joel is getting screened for the procedure the doctor admits that “technically speaking the procedure is brain damage” (Eternal Sunshine). Joel is essentially destroying himself, by destroying his memories.

The audience experience’s the process from two settings, within Joel’s mind, and within his apartment (where the Lacuna technicians operate). Throughout the process Eternal Sunshine employs lighting changes, an elaborate set of surrealist scene transitions, and present a foil to Joel’s changing character, Mary Svevo. Using the scene transitions Eternal Sunshine shows the brutal nature of the mind wipe process, and using the lighting shifts it shows the transformations of character Joel undergoes. During the beginning of the process Joel starts with his most recent memory; the memory of him Clementine breaking up. Joel gets to experience the last conversation they had, and he gets to maintain the mentality that he’ll be happier once he forgets it all. “Look at it out here. It’s falling apart. I’m erasing you Clementine, and I’m happy” (Eternal Sunshine) But is Joel really happy with it?

As previously established, the color blue follows Joel in moments of sadness and regret. As these scenes unfold, Clementine is silhouettes by blue light as she leaves his apartment for the last time, and blazing blue streetlights illuminate the night as Joel pacing back and forth on the sidewalk. From Joel on the sidewalk, the camera pans suddenly to Joel facedown on the street. Joel’s body violently jerks up, and all of a sudden, he’s sitting on his coach with Clementine eating Chinese food. This aggressive transition serves to show the audience that Joel is not in control of the process. His apathy towards the past has swept him up, and has begun to wipe out important memory after memory.

In demolishing these poignant memories Joel is demolishing defining moments of his life. The memory of a morning conversation between him and Clementine is a perfect example.

CLEM: You don’t tell me things Joel. I’m an open book. I tell you things. Every damn embarrassing thing.

JOEL: Constantly talking isn’t necessarily communicating.

CLEM: I want to know you Joel… I don’t constantly talk. People have to share things. That’s what intimacy is. I’m really pissed that you said that to me. (Eternal Sunshine)

Before this conversation goes sideways the lighting is neutral, but as soon as Joel’s insecurity is revealed a spotlight hits him. Eternal Sunshine uses spotlighting in this scene, as well as others, to indicate important moments of change for Joel. By reliving this conversation, Joel is able to reflect on his fears and flaws. One of the reasons Joel and Clementine’s relationship sank was his fear of intimacy, and his lack of assuredness towards his self. But, through this memory Joel can hope to face, deconstruct, and understand those flaws about himself. Too bad he’s chosen to erase them, and has essentially preserved traits that imped his ability to form meaningful connections with others, and subsequently his happiness. This same use of spotlighting is repeated, but to greater effect. When erasing the memory of Clementine and him lying on the Charles River together. There Joel realizes something: “I could die right now Clem. I’m just so happy. I’ve never felt that before. I’m just exactly where I want to be” (Eternal Sunshine). At this moment Joel realizes he’s only ever felt true happiness when he was with Clementine. Like many others throughout human history, Joel discovered the liberation and the salvation in finding someone who completes you. And, from reflecting on that memory before it’s erased, Joel changes his mind. Eternal Sunshine hits Joel with that familiar spotlight, for he’s a changed man now.

He wants to call off the operation. He throws he’s arms in the air, begging like a man begging to God to stop the procedure. From his relationship with Clementine Joel learned how to feel. He experienced the world in its fullest, and from that experience he was utterly satisfied, and utterly happy with his life. He’d transformed himself into a happy human being. Now he’s about to erase it all, and he’s afraid. This heartbreaking realization Joel makes hits the audience hard. Throughout the movie Eternal Sunshine has guided the readers emotions, sympathies and realizations to follow Joel’s using precise cinematographic elements. As Joel understands what made, and makes him his happiest self, so does the viewer. Joel’s transformation transforms the viewer. The appeal of becoming numb to one’s past is destroyed by Joel’s character transformation. And, Eternal Sunshine further proves to the viewer the catastrophic consequences of living with the idea that ignorance somehow equals bliss through Mary Svevo’s character.

With Mary, Eternal Sunshine is able to present the arguments advocating for the blissfully ignorant, and then subsequently refute them. She occupies the technician setting during Joel’s memory wipe. She envies Joel is wiping his memory, and “profoundly” quotes Freidrich Nietzche: “Blessed are the forgetful, for even they get the better of their blunders.”

But how true does this tightly packed “inspirational” message prove to be? Joel has shown that the forgetful absolutely do not get the better of their blunders. By forgetting his follies and flaws, Joel loses the opportunity to correct himself, or, in other words, to get the better of his self. The mentality Mary holds is best summed up by thinker Mathew Arnold: “They should think it enough to follow action for its own sake, without troubling themselves to make reason” (Arnold 35). What Mary is doing by quoting Nietzsche is being apathetic. She believes her life will just unfold in front of her, and if she makes a mistake in her actions or decisions, well then there’s nothing to do about it except try to forget. But, as Joel has shown, this mentality is exceptionally destructive, especially towards one’s happiness, and sense of self. Your sense of self is invested in your mistakes and how you respond to them. If you don’t respond to them at all, not only do you make your self meaningless, but you also destroy your chances at happiness. As Arnold describes, you must reason out your actions, you must reflect on them as Joel has, and transform yourself for the better. If the viewer wants to strive for perfection, they must act as Joel has acted and become reflective, not apathetic. Also, from Mary’s reliance on neatly packaged quotes Eternal Sunshine exposes another wrong to the viewer. The pursuit of happiness is not achieved through quick little epithets of inspiration wisdom. If the viewer hopes to achieve “perfection” they must study comprehensiveness that great works of art have to offer. A sentence has no revolutionary power. A viewer, or reader, must invest themselves in the characters, and elements of a great work of art, and transform with those character if they at all hope to reconstruct their deconstructive mentalities.

Ultimately Mary comes around to discover her mistake. It’s revealed to her that she had the operation done when she tries to reconnect with the man she erased. She hates herself for erasing her memory, realizing just as Joel realized, that she was truly living her life, truly happy, and truly a human being when she was with that person. Thus, again does Eternal Sunshine advocate for reflection over apathy.

Eternal Sunshine is as a must watch for anyone struggling to come to terms with their past, just as Siddhartha is a must read for anyone struggling to discover themselves. Eternal Sunshine is uniquely a great work of art. It holds fast in opposition towards the wave of industrial distractions, and fights to prove itself with its expertly used cinematographic elements. Through the medium of film, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind performs as well as any piece of classic literature. It ties its audience to its characters, and takes them on a journey of self-reflection and transformation that’s ultimate destination is happiness.

Works Cited

Arnold, Matthew, and Jane Garnett. Culture and Anarchy. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Gondry, Michel, director. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. 2004.