If you were alive in 1995 (which I wasn’t) and remember that year’s Oscars (which you probably don’t), then you’ll recall that Forrest Gump won not one, not two, but six awards. As the fifth highest grossing movie of its decade and, according to a quick google search, the most quoted movie of all time, the film easily won over the hearts of many Americans. People find the characters, most notably Forrest, to be lovable and the many events of the film to be both heart-wrenching and heartwarming. But if creating a successful movie is as easy as making a charming character and throwing in a few emotional twists, then what is stopping every other film in Hollywood from winning six academy awards?

The obvious place to start is with Forrest himself. If you were to describe the movie to someone who had never seen it, Forrest’s character would likely come across as a slightly less intelligent version of a stereotypical male character; he’s an athletic guy who is in love with his childhood best friend, he’s a war hero, and he starts a business that becomes successful. Sure, he had to deal with some bullies, but what relatable male character doesn’t? Anyone who has seen the movie, though, knows that he isn’t every other male in film. In fact, his masculinity, the very thing that defines many of Hollywood’s best-known characters, is shaky at best.

His intelligence, or better said, his lack of intelligence, is one of the first places we start to see his masculinity wobble. Historically, males have been seen as more capable and more fit for intellectual discourse. And beyond that, until recently it has been the case that girls, not boys, have been denied the ability to receive an education and have struggled to obtain this opportunity. But Forrest, a boy, gets turned away from school. And his mother fights to get him enrolled. So right off the bat, we watch Forrest become feminized.

Moreover, throughout the movie, we see Forrest open up about his emotions—a characteristic associated with being feminine—rather than keeping them locked up and trying to remain stoic. When he’s on the shrimping boat with Lieutenant Dan, his superior in the Vietnam war, and the storm hits, he tells us, “now me, I was scared”. Lieutenant Dan, on the other hand is the epitome of masculinity. He’s shirtless, he’s pumping his fists, and he’s got an American Flag waving behind him. And the no legs thing? No problem. He’s positioned himself so that he’s taller than anybody within miles and miles. But who do we relate to? Not Lieutenant Dan. He’s being reckless and irresponsible. Forrest, though, who is being cautious and has been feminized? We find comfort in him.

And when Forrest finds Jenny, the said childhood friend he’s pining over, at the strip club, he tells her he loves her. Again, he’s revealing his emotions. And despite being a woman, Jenny actually takes on many of the more masculine traits that Forrest lacks. Her response to his declaration is not only to brush away his emotions, as might be expected of a stereotypical male, but to actually explain that because he doesn’t “know what love is” he is wrong. Jenny is telling Forrest that he doesn’t know enough to even merit a conversation. Sound familiar, ladies? I would put money on it that essentially every woman has been told at some point or another that she is wrong just because a man doesn’t see something the same way as her and “she doesn’t know what she is talking about”.

Jenny and Forrest’s characters are constantly crossing (and uncrossing) the gender line. Sabine Moller discusses how discusses how “Jenny symbolizes ‘drugs, sex, and rock n’ roll’, whereas Forrest’s character is oriented towards ‘Mom, God & apple pie’”. And it doesn’t require too much explaining to say that society tends to associate “drugs, sex, and rock n’ roll”, which are adventurous and bold, with men and “Mom, God & apple pie”, which immediately evoke images of domestic life, with women. The characteristics of men that are often viewed negatively are put onto Jenny, while those of women that are seen positively (the tenderness and faithfulness) are given to Forrest.

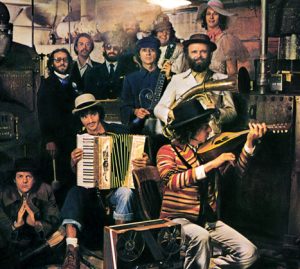

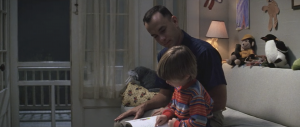

This idea of “Mom, God, & apple pie” is especially prominent at the end of the movie once Jenny has passed away. As a single parent, Forrest is left with the responsibility of being the child’s caretaker, and thus he becomes the mother figure. In fact, the film urges you to notice the parallel between Forrest having a single mother and then taking on the role of a single mother himself. At the beginning, Forrest, as a child, sits in bed with his mother reading Curious George. Fast forward to the end of the film and once again Forrest is sitting in the same room, in the same house, with the same book, and with a child who has the same name. The implication is that Forrest has taken on the role of his mother.

But don’t let this fool you into thinking Forrest is entirely feminized. Thomas B. Byers reminds us that “at the same time Forrest is, by turns, an All-American football star, a Medal-of-Honor-winning war hero, a wildly successful entrepreneur, a spiritual leader held in awe and reverence, and a fertile and wise father”. Forrest is feminized, but at the same time he embodies the idealized version of American masculinity. While he does take on the role of a motherly figure, in the scenes directly following him reading a book with little Forrest we see the two of them playing ping pong and fishing and sitting on a stump talking. Because that’s what fathers and sons do. Because we (the viewers) can’t forget that he is still a man.

Along these lines, Forrest is at once both more feminine than Jenny and the male hero to her damsel in distress. He fights the boy in the car who she was hooking up with. He fights the guy in the strip club who throws his drink on her. He fights her boyfriend who slaps her in the middle of the Black Panther Party headquarters. Forrest is, without fail, Jenny’s protector, as is the role of a true man (or so our culture says). But all the while he possesses the feminine qualities of innocence (both in the sense of being unaware of much of the bad in the world and in the sense that the first time he has sex we can assume that he is in his thirties), faithfulness (we can conclude that the only person he ever has sex with is Jenny), and compassion (he cares deeply about the people in his life and goes out of his way to help them). It is, after all, Jenny who successfully asks Forrest to marry her, and not the other way around, as gender roles would dictate. The film employs the volatile nature of gender to pick and choose the best traits of each gender and bundles them up into the lovable Forrest Gump.

It isn’t just Forrest and Jenny, though, that are subject to an unstable gender, it’s us too. We (quite obviously) experience much of the story through Forrest’s narration. He is telling us his memory of the many events. He is inviting us to see through his eyes. But those eyes, as I have established, aren’t so straightforwardly male. And if they aren’t consistently male, then neither are we. We are straddling the gender line right along with Forrest.

But it is just as important to note that we aren’t always in his point of view. In one scene, Forrest says that he thought about Jenny all the time, and then (unknown to him) we see her wiping away cocaine and standing on the ledge of a building. It is during this shot that our gaze is most voyeuristic and most masculine in that it “builds the way she is to be looked at into the spectacle itself” (Mulvey). The camera pans parts of her body and focuses on her face in a way that is distinctively male. But in this moment, we are most unhappy. We, as the viewers, are watching Jenny struggle with her cocaine addiction and potentially commit suicide. It is one of the more unsettling and dejected scenes in the movie. Certainly, the later death of Jenny and that of Forrest’s mother are both sad, but they are portrayed peacefully, and Forrest seems to come to terms with them. Here, we are thrown into an unexpected scene of drugs and danger. The purely masculine perspective is created such that viewers feel most uncomfortable in it. The scene is admitting that there are indeed issues with the traditional masculine experience.

Our perspective at the end of the movie changes again. Once Forrest goes to Jenny’s apartment where he meets their son, we are no longer listening to Forrest tell us the story. Now, while we still sometimes associate with Forrest, we are not bound to his perspective. We often find ourselves in Jenny’s point of view too. But not the “drugs, sex, and rock n’ roll” Jenny that we knew before. Oh no, this Jenny is entirely feminine. She takes on the role of a typical woman with a son and a husband, she’s a waitress (a very common job for a woman), and she dresses in the mainstream feminine way. No more hippie outfits or sequin tops with platform heels. She wears her uniform and sweaters and turtlenecks. And with her transformation comes the accepting of her love for Forrest. We watch affectionately from Jenny’s position as Forrest goes to meet his son. And after her death, Forrest is looking directly at the camera when he addresses Jenny’s grave and tells her about how things are going. In this way, he tells us how much he loves us and we are inclined to reciprocate that feeling. Now that Jenny has learned to accept her love for Forrest, we get to experience that love for him through her.

Not putting us in Jenny’s point of view until she has reached a place where she is a “normal” female and has embraced her love of Forrest is very intentional. Up until this time, we want something more for Jenny, but do not identify with her. In making Jenny more masculine, we learn to dislike women who don’t fit the normal gender roles. Then, when she does fit our desired mold, through her perspective we feel loved and content that we are back to being completely feminine. By throwing the audience around in our gender role, the movie allows us to experience the good and bad of many different perspectives. And we find that we desire to be the perfect female.

Now Forrest on the other hand, we like that he isn’t entirely masculine. By projecting some feminine traits onto him and ridding him of the unpleasant male qualities, he becomes an idealized version of a man. But he is still just that. A man. He is, though, a man that we love, especially once we are in the point of view of a feminine woman. So the movie is telling us that women should be perfectly feminine, which by definition means being inferior to men. But it makes this desire easy to swallow because it implies that if a woman becomes perfectly feminine, she won’t actually need to worry about being completely dominated by a man because he will be a feminized man—one who will still be her Prince Charming, but will also lighten the burden of the feminine role. The film admits that the most masculine of men have flaws, and in doing so gets the female to accept the better version of a man. This, I would argue, is what makes the film so impressively popular—women feel as though there is a better solution for them, while at the same time men feel comfortable that they aren’t stripped of their dominant role in society.

To make things even more complicated, Steven D. Scott argues that because of his honesty, bravery, and loyalty, “Gump, in effect, becomes America in this movie”. Thus, the idealized version of a male is also the idealized version of America. And if this is true, then being entirely feminine is equivalent to being the nation’s subject—a devoted American. The film encourages us to want to stay in line and be the perfect American because it says the country will love us back in return. All of this is not possible without the fractured nature of gender roles. It is these transgressive gender roles that tell us to accept (and thus not stand against) the problems we see in our nation. So if you are one of the millions of Americans who love this movie, then you are admitting that you love the idea of embracing every action of the government and every aspect of culture, including the racism, sexism, homophobia, and xenophobia that comes along with it.