Picture this: a group of college kids, tired from the hours of studying, reading and problem sets of the day, gathered on a collection of chairs and bean bags on a Saturday night. They are laughing hysterically, falling out of their seats as tears roll down their faces from sheer enjoyment. Now imagine another scenario: a family gathered on a couch after their wonderful teenagers get home from sports practice/choir rehearsal eating ice cream sundaes, though struggling to eat them, because every time they put a spoonful in their mouth, they start laughing and nearly spit it out. Now I’m sure you are wondering, what is it that these groups of people seem to be enjoying so much? There are actually a lot of possibilities here: Saturday Night Live, The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, The Interview, or something else entirely. But why these examples in particular? What do they have in common? And what do they say about pop culture in general? By taking you through a movie that is similar to the former examples, these answers will, hopefully, become clear.

If you are familiar with American history at all, you’ve probably heard of the Watergate Scandal. Nevertheless, it is important to explain it for this essay’s purposes. Basically, in June, 1972, burglars were arrested inside the Democratic National Committee’s office in the Watergate building in Washington, D.C., trying to steal secret documents and wiretap phones. These burglars were connected to Richard Nixon’s reelection campaign, and Nixon tried to cover up the scandal with a multitude of illegal activities, though he was eventually caught. But don’t worry, this is not a history paper. This knowledge just provides important context for the movie I will be discussing, Dick, which is the ultimate parody of the scandal. The concept of parody is an essential one in beginning to understand the answers to the posed questions. Parody is an important connecting factor of the various movies/TV shows I’ve listed. Parody is something made to pick on something else. SNL makes fun of current political figures, The Interview pokes fun at America’s intelligence agencies and Kim Jong Un, and every other example picks on something else. And, as you may have guessed, Dick picks on Richard Nixon and the Watergate Scandal. So we’ve established that the media making people laugh are, indeed, parodies, but what does this mean? What are the parodies doing that is making them so appealing to consumers and evoking such enjoyable responses?

For starters, the title, “Dick,” makes it clear that the movie is not to be taken seriously. In fact, the movie can be seen as a giant dick joke in the sense that “Dick” Nixon is portrayed as a joke of a president, and the fact that the movie itself is riddled with jokes about the male genitalia. First of all, the two teen girls, who are the main characters and are, spoiler alert, behind the reveal of the Watergate scandal, refer to the president as “Dick.” He is the president of the United States, but they do not refer to him as Mr. President, or anything respectable in the least. And when one of the girls falls in love with the president, she proclaims that she loves Dick. This, obviously, has a raunchy double meaning. Then, there is the whole Deepthroat joke. Deepthroat is the name of the secret informant(s) who gave two journalists information on how Nixon was involved in the scandal. And Deepthroat was none other than the two girls. And why did they call themselves this? Because the brother of one of the girls had just been caught watching a pornography video with the same name, which is an incredibly crude way to choose a pseudonym. The last dick joke that I recall is when the two girls, very upset with Nixon, hold up a sign as he flies over their house in a helicopter saying “You suck, dick.” I don’t think I need to explain this one But you get the idea, there are a bunch of distasteful usages of the word “dick” in this movie. The purpose of this type of humor is to make it clear that the movie, in its entirety, is a crude joke.

The most notable humor however, that makes this type of parody special, lies in the relationships between characters. The crude dick joke theme establishes the fact that the movie is, in fact, totally non-serious, but the relationships take the parody further. These relationships, especially between the president and the girls, are totally flip flopped compared to the norm. The girls have so much power over the president, which is very much atypical. First of all, they are the reason that the Watergate break in was discovered in the first place. When sneaking out one night from the house of one of the girls, which happens to be in the Watergate complex, they leave tape on the door and draw attention to security. During the aftermath of this discovery, they see some of the CREEP members, which becomes a huge issue. They visit the White House with their school the next day and spot a member, hear sneaky conversations, and see suspicious paper shredding activity, though they realize nothing of what they are seeing. The film dumbs them down to make the power they have over the president appear even more atypical. The president makes them the official dog walkers of the White House because he thinks they know too much and wants to keep an eye on them, when in reality, they don’t know that they know anything. Here, we can see how these girls have power over the president of the U.S. as ditzy and clueless children.

The power shift doesn’t end here though, it goes much farther. The girls make cookies for the president in which they, cluelessly, add marijuana from the brother’s secret stash. There are jokes made explaining why Nixon is paranoid that are linked to the discovery of this secret ingredient. The weed cookies also lead to an accord with the Soviet Union because Nixon and Leonid I. Brezhnev eat them together and end up happily getting along. Just think about this for a second. Two girls, portrayed as even dumber than average, bake weed cookies for the president and, essentially, save the world from nuclear war. They are literally drugging the president and influencing America’s foreign affairs. And it goes even farther. They tell Nixon that war is wrong, and he proceeds to begin the Vietnam peace process. They are referred to Nixon as his “secret youth advisors” (Dick). The biggest accomplishment representing the girls’ power over the president is their eventual reveal of the Watergate Scandal, which ends Nixon’s presidential career. And it happens only because one them, while leaving Nixon a love message on his tape recorder, accidently plays back a message featuring him being cruel to his dog and a multitude of scandal proof. But of course, the girls are upset about the dog alone, and only reveal Nixon’s scandal to avenge the dog. So these girls are the reason why the Watergate Scandal is revealed all because they are animal lovers. As I’ve emphasized already, these girls have a total power over the president that they have no business having.

The power shift doesn’t end here though, it goes much farther. The girls make cookies for the president in which they, cluelessly, add marijuana from the brother’s secret stash. There are jokes made explaining why Nixon is paranoid that are linked to the discovery of this secret ingredient. The weed cookies also lead to an accord with the Soviet Union because Nixon and Leonid I. Brezhnev eat them together and end up happily getting along. Just think about this for a second. Two girls, portrayed as even dumber than average, bake weed cookies for the president and, essentially, save the world from nuclear war. They are literally drugging the president and influencing America’s foreign affairs. And it goes even farther. They tell Nixon that war is wrong, and he proceeds to begin the Vietnam peace process. They are referred to Nixon as his “secret youth advisors” (Dick). The biggest accomplishment representing the girls’ power over the president is their eventual reveal of the Watergate Scandal, which ends Nixon’s presidential career. And it happens only because one them, while leaving Nixon a love message on his tape recorder, accidently plays back a message featuring him being cruel to his dog and a multitude of scandal proof. But of course, the girls are upset about the dog alone, and only reveal Nixon’s scandal to avenge the dog. So these girls are the reason why the Watergate Scandal is revealed all because they are animal lovers. As I’ve emphasized already, these girls have a total power over the president that they have no business having.

The girls have power over the president, but so what? What does this power switch have to do with the success of parody as an entertainment form? And what is the big picture here? Stick with me and we will soon know the answers. Let’s start with the basics. Little girls should not have political power over a president, yet they do. And this means something big. The reason that typical rules and hierarchies are thrown away here is to actually rebel against authority. In other words, this movie is a form of rebellion among the people. Even though it is temporary, the actors and the audience, together, experience liberation from the constraints of everyday life. Laughing alongside one another makes authorities seem like humourous spectacles rather than threatening big shots. It’s almost as if people experience a temporary second life.

This type of feeling can be seen as carnivalesque, though a carnival often brings up images of Mardi Gras and Carnival. But political satire is a carnival that can be experienced by so many more people so much more often. And the idea of carnival is nothing new, there is a history of using carnival to fight oppression. It makes freedom and a hope for better things more tangible (Karolee 67). Success seems, even if it is only for a brief moment, like an actual possibility. And this optimism is so essential for an engaged public culture. Parodies copy something and then turn it into an object of attention which people see as something that can be discussed and ridiculed rather than untouchable. Parody seems to work by, as excellently summed up by Robert Harimon, “exceeding tacit limits on expression—the appropriate, the rational—but it does so to reveal limitations that others would want to keep hidden” (251). So parodies, in a way, are a path to the truth. They give the ordinary person a way to realize and talk about what is actually going on, and perhaps inspire them to even do something about it. Dick, through its crude jokes and crazy role reversals, opens up a discussion for the truth and a door for action surrounding the Watergate scandal, which is a lot of power for a seemingly innocent and hysterical movie to have.

Parody is a huge part of popular culture. I don’t know the last time I met someone who didn’t engage in it in some way. Because of this, it is no stretch to say that popular culture has often been a kind of carnival, this carnival, in it’s most popular form, being parody. And in this carnival, ordinary people set aside norms and liberate themselves from those who seem untouchable any other time. We laugh, then we speak, then we find the truth, and then, in the ideal instances, we act. All because of some distasteful, likely offensive, piece of popular culture.

This essay was read by Chloe Henderson.

Works Cited

Bakhtin, Mikhail, Rabelais and His World, Helene Iswolsky (trans.), Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1965/1988, pp. 4-11.

Dick. Dir. Andrew Fleming. Perf. Kirsten Dunst and Michelle Williams. 1999.

Hariman, Robert, “Political Parody and Public Culture,” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 94, no. 3, 2008, pp. 247-72.

Stevens, Karolee, “Carnival: Fighting Oppression with Celebration,” Totem: The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology, vol. 3, no. 1, 2011, pp. 65-8.

of their culture – is simple and spent at home because of their limited income. Their culture is their money – or lack thereof. For

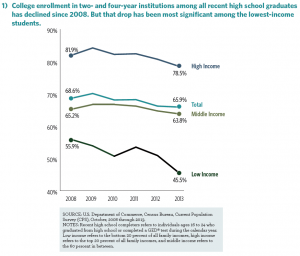

of their culture – is simple and spent at home because of their limited income. Their culture is their money – or lack thereof. For family because of their low economic status. This is equally true today. According to Census Bureau data from 2013, 78.5% of students from high income

family because of their low economic status. This is equally true today. According to Census Bureau data from 2013, 78.5% of students from high income professional writer. The professor claims that “only half a dozen [people] could support themselves as writers alone… so if you want to be an author and eat two or three times every day, there’s only one way to do it: marry money.” In this scene, the Walton’s economic status and their eldest son’s reality is exposed – his access to pursuing his dream career and culture is crippled by his poor background and lack of access to high culture. Because he doesn’t have the money to sustain himself as a writer alone (according to this professor) and since he hasn’t been exposed to high culture to have the connections to get published, the odds are stacked against JohnBoy to successfully become a writer, once again proving that culture, in the sense of career options, is not ordinary. Religion, on the other hand is a different story.

professional writer. The professor claims that “only half a dozen [people] could support themselves as writers alone… so if you want to be an author and eat two or three times every day, there’s only one way to do it: marry money.” In this scene, the Walton’s economic status and their eldest son’s reality is exposed – his access to pursuing his dream career and culture is crippled by his poor background and lack of access to high culture. Because he doesn’t have the money to sustain himself as a writer alone (according to this professor) and since he hasn’t been exposed to high culture to have the connections to get published, the odds are stacked against JohnBoy to successfully become a writer, once again proving that culture, in the sense of career options, is not ordinary. Religion, on the other hand is a different story.