Chloe Henderson

April 19, 2017

English 117 Professor Thorne

Your Not-So-Ordinary Culture

“You can be whoever you want to be.” I don’t know about you, but I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard this. That’s probably because, quite frankly, I am a middle class white girl attending an elite college in the northeast, and I am lucky enough that I probably can be whoever I want to be. But that’s not so true for everybody. And it’s not so ordinary for everybody to hear. Although growing up we often hear about this so-called “American Dream” in high school history classes, in politician’s hopeful yet ingenuine campaign speeches, and in countless CNN articles, for most people the American Dream is quite literally just that – a dream, far fetched and far flung, and it has been for a while now. I’m not just talking about who you can become for your career because I think everyone knows that not everyone is lucky enough to be able to pursue their dream career. I’m talking about culture. I’m talking about what you get to do on a Friday night and how you get to live the rest of the week. I’m talking about why your culture is not so ordinary.

Yes, culture is ordinary in the sense that everybody belongs to, contributes to, and has their own culture (even a lack of culture could be considered a culture in itself). But the type of culture you identify with and are exposed to is greatly dependent on the thickness of your wallet. So although theoretically everybody has access to culture in the same way they have access to gaining wealth by pursuing the so-called “American Dream,” like money, culture isn’t as accessible to everybody as it claims to be, thereby making culture out of the ordinary. Just as there is an elite, middle, and lower class of economic status, so too there is an elite, middle, and lower class of culture. Take for example the beloved 1970s television series, The Waltons, based on the lower class life of author Earl Hamner. The series follows the life of the Walton family growing up during the Great Depression working on their family sawmill in the small rural town of Walton’s Mountain, Virginia in the Blue Ridge Mountains. During each episode, the connection between income and culture becomes undoubtedly clear. In the home of two grandparents, two parents, and seven children, the family’s poverty is not only a central theme of the series, but also a testament to the influence of their family’s income on their culture.

The Waltons live the simple life of a farm family, growing most of their own food, getting milk from their cow and eggs from their chickens, sewing their own clothes, building their own furniture, and sacrificing one thing for another – often manual labor in exchange for goods, such as when the eldest son, JohnBoy, works for a family in exchange for their car. The family has a radio, but is “too poor to have a telephone” nor can they afford other luxuries such as a typewriter or even shoes for the children (until later on i n the series after saving money however). The wealthy life of a pair of older single sisters living together down the road from the Waltons is often used to contrast the culture of wealth versus poverty in The Waltons. The affluent sisters wear extravagant clothes for ordinary occasions – diamonds around their necks, feathers in their hair, and elegant dresses – and display their wealth in their home with their decorative lavish portraits, chandeliers, books, record player, and furniture. This greatly contrasts the simple home of the Waltons which has only necessary furniture, utensils, and the occasional decor here or there. The simplicity of their rural life is their culture. And just like any other family, their culture is their income.

n the series after saving money however). The wealthy life of a pair of older single sisters living together down the road from the Waltons is often used to contrast the culture of wealth versus poverty in The Waltons. The affluent sisters wear extravagant clothes for ordinary occasions – diamonds around their necks, feathers in their hair, and elegant dresses – and display their wealth in their home with their decorative lavish portraits, chandeliers, books, record player, and furniture. This greatly contrasts the simple home of the Waltons which has only necessary furniture, utensils, and the occasional decor here or there. The simplicity of their rural life is their culture. And just like any other family, their culture is their income.

One of the most prominent examples of the Waltons family culture is their free time. When they aren’t cleaning, cooking, building furniture, sawing wood, taking care of the children, or fixing things up around the house to make ends meet, the family spends their free time gathered around the radio listening to Franklin D. Roosevelt, playing music with each other, playing games, or walking to the nearby grocery store to buy a strip of licorice Once in awhile when there is an event in town such as a carnival or the local fair, the family will go out, but for the most part, their free time – and thereby some  of their culture – is simple and spent at home because of their limited income. Their culture is their money – or lack thereof. For

of their culture – is simple and spent at home because of their limited income. Their culture is their money – or lack thereof. For

example, the mother and father of the Waltons family could never afford to go on a honeymoon, so after nineteen years of marriage at a time when they were exhausted and overworked, Grandpa sells his beloved 1864 two cent piece for $20 to the local store, so that Momma and Daddy can take a short-lasted day trip to the beach as their honeymoon. Unlike other families that might travel frequently, the Waltons rarely ever take trips outside of Walton’s Mountain simply because they can’t afford it. Traveling isn’t a part of their culture because neither is a large income. Whereas if the Waltons had more money and were able to travel more, they would have access to wealthier culture. But since they can’t travel freely because of their financial limitations, not all culture is ordinary because it is restricted by economic class.

In 1958 a novelist and critic named Raymond Williams argued that “culture is ordinary” because “every human society has its own shape, its own purposes, its own meanings” (4). However, what Williams fails to recognize in his essay is that not all culture is ordinary because not all culture is accessible to everyone, like high class culture isn’t accessible for the Waltons. Using the example of a high-cultured pretentious tea shop in Oxford compared to his culture as a child growing up in a small farming valley in Wales, Williams argues that culture isn’t restricted to the elite because everyone has their own culture based on their “new observations, comparisons, and meanings,” (4). However, Williams fails to consider that culture is not ordinary because even though everybody has their own culture, not everybody has access to another culture they might want to be a part of. What makes you different from me or anybody else for that matter is the sum of your experiences, which have undoubtedly been influenced by your access, or lack of access, to money. I’m not saying that your values and personality are dependent on your money, because you can’t buy your beliefs. But what I am saying is that your culture depends on your money, chiefly on your access to it. Money is culture, and your money is what makes your culture more or less ordinary.

According to another theory entitled Lewis’s model, there is a “culture of poverty” that “once it comes into existence it tends to perpetuate itself from generation to generation because of its effect on the children… they have usually absorbed the basic values and attitudes of their subculture and are not psychologically geared to take full advantage of changing conditions or increased opportunities which may occur in their lifetime.” (Carmon, 404) Just like Grandpa in The Waltons has “been living in poverty for so long, [he] wouldn’t know how to get along in any other neighborhood.” Lewis’s model also suggested that there are shared personality traits among poor families, such as low self-esteem, pessimism, and loneliness (Carmon, 404). So not only is culture separated by economic class, but it is also perpetuated throughout generations and also has some effect on personality. Even though we would like to think of America as equal among all classes and cultures, it isn’t because there is an elite and middle class. But, there are similar values that trickle down from the elite class to the lower class such as the importance of education, religion, and morals.

Although we might hope that everyone has equal opportunity to become highly educated, poverty hinders this possibility. Neither of the grandparents nor the parents in The Waltons went to college, but they hope to provide this opportunity to their children. The eldest son earns a scholarship to study journalism at University while another son puts himself through music school by playing piano at the local bar. The eldest daughter becomes a doctor and can afford medical school since her husband is already a doctor, and another daughter puts herself through business school by working as the secretary at the school. Meanwhile for the other three children, college is not an option and they pursue blue-collar jobs as mechanics or for the youngest daughter, as a housewife. Although many of the children pursue higher education, that is not to say that it was easily accessible to them. All of the children in college worked part time jobs while studying to afford their education while their family at home sacrifices financial security and was constantly worried about money. For example, for their eldest son’s high school graduation present, the Walton family gave

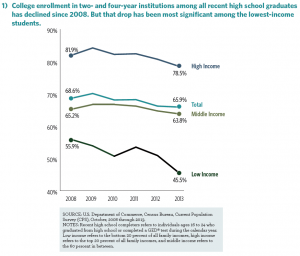

him a suit, but when their cow passed away unexpectedly, JohnBoy had to sell his suit to buy a new cow for the family so they have food on the table. Additionally, when the tire on the family’s car flattens, a younger son sacrifices his puppies to sell in order to get the car tire fixed. So although education may seem ordinary in that most of the Walton children study beyond high school, it is extraordinarily hard for them and their  family because of their low economic status. This is equally true today. According to Census Bureau data from 2013, 78.5% of students from high income

family because of their low economic status. This is equally true today. According to Census Bureau data from 2013, 78.5% of students from high income

families enroll in two or four year institutions. Whereas 63.8% of students from middle income families enroll in the same institutions. However, only 45.5% of students from low income families enroll in these academic institutions (American Council on Education, 2015). The disparity in educational opportunities for students from low, middle, and upper income families is evidence that culture is not ordinary.

Although their family encourages them to pursue their educations, the Walton children aren’t always greeted with such optimism by others who see a more realistic future for the poor children. Take for example the episode titled, The Prophecy. In the beginning of this episode, the main character and eldest son of the Walton family who attends Boatwright University on an academic scholarship, is greeted by a professor who hits him hard with a pessimistic, yet realistic truth for the Walton boy’s future as a  professional writer. The professor claims that “only half a dozen [people] could support themselves as writers alone… so if you want to be an author and eat two or three times every day, there’s only one way to do it: marry money.” In this scene, the Walton’s economic status and their eldest son’s reality is exposed – his access to pursuing his dream career and culture is crippled by his poor background and lack of access to high culture. Because he doesn’t have the money to sustain himself as a writer alone (according to this professor) and since he hasn’t been exposed to high culture to have the connections to get published, the odds are stacked against JohnBoy to successfully become a writer, once again proving that culture, in the sense of career options, is not ordinary. Religion, on the other hand is a different story.

professional writer. The professor claims that “only half a dozen [people] could support themselves as writers alone… so if you want to be an author and eat two or three times every day, there’s only one way to do it: marry money.” In this scene, the Walton’s economic status and their eldest son’s reality is exposed – his access to pursuing his dream career and culture is crippled by his poor background and lack of access to high culture. Because he doesn’t have the money to sustain himself as a writer alone (according to this professor) and since he hasn’t been exposed to high culture to have the connections to get published, the odds are stacked against JohnBoy to successfully become a writer, once again proving that culture, in the sense of career options, is not ordinary. Religion, on the other hand is a different story.

A large part of the Walton’s culture is their religion. And in this sense, yes, their culture is ordinary because they, just like any other economic class, have faith. Religion is one exception to my claim that culture is not ordinary because religion is universally accessible to everybody. Unlike other forms of culture such as art, education, customs, music, and traditions, you don’t need anything or anyone else to have religion. You have complete control over your beliefs just as the Waltons do; the mother is extremely religious – she prays every night before supper and before bed, attends church every Sunday, and frequently references God and the Bible but at the same time the father is rather atheist. The complete control over their beliefs is the antithesis of the little choice they have over the other aspects of their culture because of their low income. In an article from his book, International Review for the History of Religion, scholar Jakob De Roover argues that religion is universal across cultures and across time periods. De Roover claims that “all cultures have their ‘own’ religions; these also consist of sets of metaphysical beliefs; their practices are expressions of such beliefs; their ethics revolve around norms and values…While there is variety to the content of their beliefs, practices, norms, and laws, what remains invariant is the formal structure of such societies,” (2). This “invariant” structure is the presence of an individual’s beliefs. The fact that your beliefs are your religion and beliefs are constant across classes and culture does make religion ordinary, but not all of your culture.

Culture is not ordinary because neither is money and, let’s face it, your culture is your money. Try looking up the the ritual for newborn babies in India which is a hope to bring prosperity to the family and then tell me then if you still think culture is so ordinary. Or at least if you think an elite culture would do the same. And to that I say goodnight.

This essay was read by Drew Cohen.

References

American Council on Education (2015, November 05). Where Have All the Low-Income Students Gone? Retrieved April 17, 2017, from http://higheredtoday.org/2015/11/25/where-have-all-the-low-income-students-gone/

Carmon, N. (1985). Poverty and Culture: Empirical Evidence and Implications for Public Policy(4th ed., Vol. 28, Pg. 403-417). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

De Roover, J. (2014). NVMEN, International Review for the History of Religion (Vol. 61). Leiden: Brill.

McGreevey, J., & Hamner, E. (Writers). (1972, September 14). The Waltons [Television series episode]. In The Waltons. Los Angeles, California: CBS.

Williams, R. (1958). Raymond Williams on culture and society: essential writings. London: Sage.