Drew Cohen

Due 5/16/17

English 117 – Christian Thorne

White as a Flipping Gh-gh-gh-gh-gh-gHOST!!!!!

Perhaps you’ve heard about this before, but apparently you can be taught to fear people of mixed race. Now, obviously you’re not going to call the police and run screaming if your half-Asian best friend turns the corner too quickly, but on a more subtle level, you can be tricked into thinking that mixed race people are untrustworthy and that they maybe even “give you the creeps.” You may believe that you’re above such prejudice, but keep reading, and I can prove that racial purism can be made subconsciously appealing to you.

Race, as you might imagine, is not only determined by skin tone: throughout history, racial scripts and the societal roles of people of different races have defined race as just as much a cultural phenomenon as a pigmentary one. As such, being mixed race might allow you to not only experience multiple racial cultures in daily life, but to also have the freedom to choose which race you align with more. Studies like one by Miri Song of The Sociological Review have shown that people of mixed race tend to “choose one race as their primary basis of identification” (Song, 2010). But at the same time, society tends to enforce a “one drop rule,” especially on African Americans, such that even “part-Black people are expected to see themselves as black” (Song, 2010). In cases of misalignment between socially-expected and self-conceptualized racial identity, choosing to identify with a race that is unexpected of you can be seen as something like wearing a mask: the you that the world sees is not the real you.

In this case, if you want to consider how masking true identity can play into anti-mixed-race stigma, simply look at a classic series that bases much of its own cultural identity on “unmasking” monsters: the Scooby-Doo franchise.

From left to right: Fred Jones, Daphne Blake, Scooby-Doo, Shaggy Rogers, and Velma Dinkley. Above them is a spooky, spooky ghost.

Scooby-Doo is a kid-friendly mystery series all about uncovering the “masked madmen around the world” as the lovable Great Dane, Scooby-Doo, and his four teenaged friends in Mystery Inc., Norville “Shaggy” Rogers, Daphne Blake, Fred Jones, and Velma Dinkley, travel in their flower-power “Mystery Machine” van to solve the world’s spooky puzzles (Elzinga and Wolfswinkel, 2011). And if you don’t already know who Scooby-Doo is, that’s “like, totally uncool, man.”

This guy’s pretty uncool.

Quite seriously, a study by neuroscientists at CU-Boulder found most college students to have adept semantic memory of the Scooby-Doo theme song, finding that these students could remember and fill in a missing word at any point in the song (Overstreet et al., 2015). Scooby-Doo is a genuine household name in any of its many iterations, from the original Scooby-Doo, Where Are You? cartoons to the reboot series What’s New, Scooby-Doo? and beyond.

Notorious among this notoriety is the 2002 live-action movie, Scooby-Doo. Andrew O’Hehir of Salon.com notes that the movie is “lowbrow” and “tries to walk that same well-worn line of simultaneously spoofing a classic TV series and remaining true to its spirit” by reuniting a disbanded Mystery Inc. and crudely making fun of the clichés of the original series and its characters (O’Hehir, 2002).

Mystery Inc. in 3-D.

And with language that includes the words “bi-otch,” and lines like “I would have gotten away with it too if it weren’t for you meddling sons of-” and “you don’t have the scrote for this job,” you can clearly see that this is a movie for nostalgic teens and adults that, alongside wanting to see Daphne with actual, human breasts and Freddie Prinze Jr. with bleached hair, feel the urge to relive their nostalgia of the classic Scooby-Doo experience outside of the second dimension.

Yet more significant than this slightly more adult interpretation of the series is the way that the movie honors the clichés of the original cartoons by flipping them on their heads, the classic “unmasking” a notable example. Freddie Prinze Jr.’s Fred insists at one point in the movie that Mystery Inc.’s “area of expertise is nut jobs in Halloween masks,” and claims that ghosts and monsters aren’t real. Or, at least he does until they are real.

And Velma said, “Let there be sunlight!”

Rather than playing up the man in the mask like the cartoons do, the movie utilizes man as the mask: the movie’s monsters can’t survive in sunlight and need to use the human body, as Velma says, “like a human suit, SPF 1,000,000,” after removing the human’s spirit from his or her body. Along the same lines, the true villain of the movie is the obnoxious Scrappy-Doo, a pint-sized pup with a glandular problem who disguises himself in, you guessed it, a human suit: the “Mr. Mondavarious” that invites Mystery Inc. to his amusement park is really Scrappy-Doo in costume.

Does this immediately instill fears of multiracial people in you? To understand why it might, you need to first understand Richard Dyer’s arguments on the embodiment of whiteness. Dyer argues that “to represent people is to represent bodies,” but for white people “whiteness involv[es] something that is in but not of the body” as “white people have a peculiar relationship to race, of not being quite contained by their racial categorization” (Dyer 14,18). In this way, white people can “transcend” their bodies, since their racial identity does not limit them to judgment based on their physical appearance (Dyer 17). The white identity is thus unique because it is more spiritual than physical – Dyer even mentions Christianity as an embodiment of whiteness. It makes sense then that essentially all of the possession victims in the movie are white, including Fred, Velma, and Shaggy’s new love interest, Mary Jane. In order to be possessed in this movie, you need to be able to allow your spiritual identity to transcend and be separated from your physical one and have your spirit removed from your body.

The Voodoo Maestro.

This might also explain why a certain black side character, the Voodoo Maestro (yes, that is the only name they give him), can resist possession. Of course, you can see in the movie that part of the Voodoo Man’s protection comes from his voodoo rituals, but the underlying ideology is crucial here: the one visible, semi-important black character in the movie has protection from possession. The movie hungrily consumes Dyer’s argument like Shaggy and Scooby eat Scooby Snacks.

To this effect, the possessed humans in the movie are reminiscent of classic movie zombies.

In one of the movie’s action scenes, a possessed Fred and his legion of white bodies chase Shaggy and Scooby into a shed, the monsters attempting to break in by reaching in through holes in the wall. Sound familiar? You might recognize this from every zombie movie ever.

Don’t they look cuddly?

Physically reaching in or out is a classic feature of zombies from Night of the Living Dead to The Walking Dead, and the “trapped inside with zombies outside” scene like the one in this movie is an unmistakable cliché. Justin Ponder of The Journal of Popular Culture notes that “the first reason that zombies horrify is that they are impure” and that they “defy boundaries considered not only social but also natural, the separation between live and dead enforced not by social institutions, but by the very laws of nature” (Ponder, 2012). You can see similar impurity in the movie’s “zombies” in their language. In an attempt to effectively emulate the speech of “today’s young people,” the monsters are taught “faux hip-hop lingo” (O’Hehir, 2002). One of the movie’s more comedic moments happens when a possessed white girl named Carol throws her friend and yells “back off my grill, son!” The possessed are notable for sounding different than you would expect them to by their looks: they look white and speak with stereotypically black, “hip-hop” language. Compare this to the Voodoo Maestro’s stereotypical language (“why you all up in the voodoo ritual space?”), which isn’t seen as abnormal. Similar to zombies, “mulattos” or, half-black, half-white people, once “horrified” people because they were “racially impure” (Ponder, 2012). While zombies were impure for being both living and dead, mixed-race people “def[ied] the racial dichotomy upon which life in North America stood” and were long considered impure themselves (Ponder, 2012). Remember how the possessed are essentially white masks for monsters? The movie’s ideology demonizes people trying to “pass” as white.

RAARRRRR! LOOK HOW WHITE WE ARRRRRRRE!!!

But the unmasking cliché isn’t the only one flipped in this movie. Alongside its prejudicial racial scripts, Scooby-Doo fortifies its female protagonists with narratives of female growth and empowerment. Velma is empowered by being given the attention, publicity, and respect she deserves for her “brainwork” on Mystery Inc.’s cases. At the same time, “damsel-in-distress” Daphne becomes a black belt and plays a huge part in saving the day rather than just “getting captured again.”

Definitely not her anymore.

Victoria Anne Newsom of Femspec gives us a definition for girl power, “the ability for young women to achieve personal empowerment while maintaining a distinctly ‘girlish’ style” (Newsom, 2004). By this definition, Scooby-Doo is abound with “girl power,” but to a somewhat harmful extent. Velma laments always being “picked last” and that guys like Fred “only care about supermodels” (which leads to one of Fred’s most classic lines: “I’m a man of substance. Dorky chicks like you turn me on, too”). What’s a good sign of Velma’s eventual empowerment? Perhaps her possession by the monsters (an essential loss of agency) and a resulting “hot girl” makeover, including a new hairstyle and more revealing clothes than her classic “look at me, I’m Sandra Dee” turtleneck.

Yeah, she’s pretty smart, but that eyeshadow game is on point!

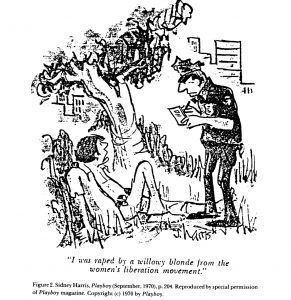

An inversion cartoon featuring a male rape victim.

And Daphne’s fighting ability makes her story similar to an “inversion cartoon,” which, as Joyce Hammond of The Journal of Popular Culture describes, “depicted women and men in a manner which inverted societal expectations” (Hammond, 1991). These inversion cartoons were often “created by men for men” and used in Playboy magazines, while also aiming “primarily at white audiences” with white people “overwhelmingly depicted as characters” (Hammond, 1991). So when Daphne helps save the day by fighting and defeating the stereotypically hispanic luchador Zarkos, the “famous masked wrestler” whom “you may recognize from Telemundo,” she actually applies yet another racial script to this movie – white women can be “empowered” through their girliness, essentially at the expense of marginalized races, and often to tailor to male gaze.

When you get down to the details, the girl power in this movie is hardly honorable. But the key here is, as Andrew O’Hehir puts it, “mid-’90s nostalgia” (O’Hehir, 2002). Look at the girl power in TV shows from the 1990s like Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Sailor Moon and you’ll see this female empowerment through “hyperfemininity and youth” (Newsom, 2004). But the Scooby-Doo movie rips this off completely, actually casting Sarah Michelle Gellar, a.k.a “Buffy,” as Daphne to make her seem more capable and badass.

I feel like I’ve seen her somewhere before, maybe with red hair and vibrant purple clothing?

Scooby-Doo masks its harmful racial narratives by playing up nostalgic girl power, which we don’t recognize as problematic because calling out women’s empowerment as problematic is inherently sexist. What you get in the end then is a masking of the bad with the bad, and it works because, as Joyce Hammond mentions about inversion cartoons, “the audience identification with the cartoon characters was a significant aspect” and the cartoons “carried messages for the predominantly white male or white female audience” (Hammond, 1991). When white audiences see the white female protagonists they grew up with achieve personal victories, they don’t notice that they’re being conditioned to fear the “mulatto” monsters of everyday life. Jinkies! Find me a better unmasking than that and I might just let you have a Scooby Snack.

This essay was read by Chloe Henderson and modeled after the style of David Foster Wallace.

Works Cited

Dyer, R. (1997). The matter of whiteness. In R. Dyer. White. London: Routledge, 1997.

Elzinga, Luke and Wolfswinkel, Kelsey (2011) “Scooby-Doo 101,” Ethos: Vol. 2011, Article 11. Available at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ethos/vol2011/iss3/11

Hammond, J.D. (1991), Gender Inversion Cartoons and Feminism. The Journal of Popular Culture, 24: 145-160.

Newsom, V.A. (2004), Young Females as Super Heroes: Super Heroines in the Animated Sailor Moon. Femspec, 218: 57-81.

Ponder, Justin (2012), Dawn of the Different: The Mulatto Zombie in Zack Snyder’s Dawn of the Dead. The Journal of Popular Culture, 45: 551-571.

O’Hehir, Andrew. “Scooby-Doo” Salon.com. 14 June 2002. http://www.salon.com/2002/06/14/scooby_doo/. Accessed 12 May 2017.

Overstreet, M.F., Healy, A.F. and Neath, Ian (2015), Further differentiating item and order information in semantic memory: students’ recall of words from the “CU Fight Song”, Harry Potter book titles, and Scooby Doo theme song. Memory, 25: 69-83.

Song, Miri (2010), Does ‘race’ matter? A study of ‘mixed race’ siblings’ identifications. The Sociological Review, 10: 265-285.