In late summer of 1977, the two spacecraft of the United States’ Voyager program were launched. The primary mission of these unmanned NASA probes was not much different that that of earlier ones: they would pass by a few planets, collecting data on the way. Their final trajectory, however, was something new. Voyagers 1 and 2 would be the first manmade objects to exit our solar system. Seizing on this opportunity, Carl Sagan set up a team to create some sort of message that could be attached to the probes in case they were ever found by other intelligent beings. The result of their work was the Voyager Golden Record.

This gold-plated copper “vinyl” contains audio recordings of sounds from our planet—a passing train, laughter, thunder, animal calls—along with encodings of photographs—net fishing, a man hiking with his dog, a jet liner taking flight, Jane Goodall with some chimps, a diagram of DNA. It also contains recordings of greetings in various languages, a message from the United Nations, and—comprising the majority of the record’s playing time—music (NASA). Although the selections for all sections of the record have been controversial (for example, NASA did not allow the inclusion of images of nudity due to political backlash from the Pioneer spacecraft plaques) the music has received particular attention. While the rest of the record contains things that people undeniably see or hear, the music is something more. Music is how people interpret these experiences. It is how we understand what it means and feels like to be a citizen of Earth. It is ninety minutes not of human noises, but human culture.

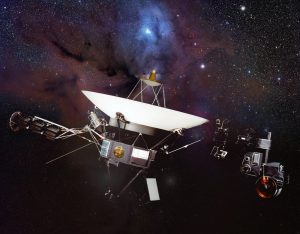

An artist’s concept of Voyager 1. A copy of the Golden Record is visible on its side.

The music on the record comes from a diverse range of geographic locations, including all six populated continents and Pacific islands. There was large effort put into representing geographic and economic diversity, but certain choices stick out. As Gorman has noted, certain groups whose music was recorded are also ones that were singled out in early anthropological work as “primitive” (270). Racist underpinnings aside, two out of twenty-seven songs do come from hunter-gatherer groups, the Pygmies of Central Africa and the Australian Aborigines. This may seem like a disproportionate emphasis, considering the low numbers of contemporary hunter-gatherers worldwide. Ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax requested the inclusion of these pieces on the Record for specific reasons. By continuing the way of life practiced during the first 99% of human history, the Pygmies and Aborigines represent diversity not only geographically, but also temporally (Cultural Equity). The inclusion of their music on the Record constitutes the preservation of a disappearing way of life, not just a presentation of humanity’s culture, and as such, is more than just a means of musical diversity. In Man the Hunter, Marshall Sahlins provides his theory of “the original affluent society”. Sahlins demonstrates that modern hunter-gatherer societies enjoy a remarkably high quality of life, working only five hours a day and having more time to sleep than any other group on Earth: all by relying on natural processes, rather than engineered creations, to provide for them. Abundance in subsistence, long foreshadowed in literary imaginations of a nonconsumerist ideal, suggests that technological and social progress is not the solution, but the problem. Many theorists have proposed that the content of all cultural material is driven by hope for an emancipatory future (Ernt Bloch is probably the most important in this movement): the Golden Record invites us to look to the past for utopia.

Although the music on the records comes from a variety of traditions, there is a clear focus on Western music, which is included in the forms of classical and pop. The reasons for this are quite obvious: Western music is the music of the producers of the Record. Western music is also the form of music that was becoming increasingly understood as being distant from the people, even as suppressing the commoner and perpetuating the hierarchies of industrial life (theorists Theodor Adorno and Louis Althusser are important proponents of this line of thought). What is interesting is that the pop selections are ones that strongly contradict this thinking. For one thing, the three pop artists are Chuck Berry, Louis Armstrong, and Blind Willie Johnson: they are black, members of one of the most repressed groups in America. The Chuck Berry selection is “Johnny B. Goode”, the song that practically invented rock and roll. Louis Armstrong’s “Melancholy Blues” is a classic example of impromptu jazz. But the third artist is little known. “Dark was the Night” by gospel-blues Blind Willie Johnson is perhaps the most interesting choice on the record. He is a genuine example of a commoner. Although his talent allowed Johnson to be recorded during his lifetime, he only gained mass following after his death. His life is still largely a mystery, despite the work of historians, although it is known that Johnson was a small church preacher before becoming homeless (Pinkard). These artists are interesting in that all are known best for their trend-setting innovations. These were early works in their respective areas. The makers of the Record recognize the black origins of Western pop music, and select works that illustrate this over derived works. The implications of this decision are twofold: there is nostalgia for the early days of pop, when everything was fresh and new; there is no inclusion of the modern restrictions by race and class in the making of culture, allowing music to be composed, even in its industrial form, by the layperson. Once again, it is evident that important elements of the Record are strongly associated with great parts of the past.

The actual content of the music, of course, is of upmost importance in choosing what we will be sending to the extraterrestrials. Stemming from a broad range of places, the music inherently has a great diversity of styles. The pieces also encompass a broad range of emotions (at least within human interpretation). And interestingly, not all of these emotions are positive ones. As Nelson and Polansky have noted, although pain, injustice, and death are large parts of human life, no images or sounds of any of the “darker side of humanity” have been included on the record: the only suffering that exists is that which we recognize in the music (373). Within the contents of the record, music almost serves as the opposite to the utopian ideal. Rather than creating an experience separate from pain, the music is the only material on the record that contains any pain. “Dark was the Night” and “String Quartet Number 13 in B Flat” are quite sad, while “Beethoven’s Fifth” is commonly interpreted as angry sounding. But these pieces area, of course, often praised for how well they represent such feelings. Music has this ironic way of allowing us to reconcile with such emotions rather than augmenting the associated suffering. Through its empathetic powers, music puts evil in a state that can be approached, processed, and understood. On the Record, evil exists only in this conquerable form.

For these reasons, the music on the Voyager Golden Record comprises a “nostalgic utopia”, a material that allows listeners to return to the perfect world of the past. It still may be hard to see the contents of the disk as nothing more than an incoherent conglomeration. The collection of sights and sound on the Record have never coexisted: they all come from separate cultures and separate times, each with their own individual histories and meanings. But long after all other forms of these songs have been lost from this Earth, long after this Earth has been lost, the disk will continue to drift through interstellar space, and the songs will only exist only in this form: together. As this synergistic assemblage, what we are sending to possible extraterrestrials is not only the best humanity has ever been, but also the best humanity could ever be. It is a perfect future made up of the past.

One of the original copies of the Voyager Golden Record. Through close inspection, one can make out the handmade inscription:

“To the makers of music — all worlds, all times”

Works Cited

“Alan Lomax and the Voyager Golden Records”. Cultural Equity. http://www.culturalequity.org/features/Voyager/

Ferris, Timothy. “The Mix Tape of the Gods” The Opinion Pages. The New York Times. September 5, 2007.

Gorman, Alice. “Beyond the ‘Morning Star’”. In Best Australian Writing 2014. Ed. Ashley Hay and Ian Lowe. Kensington: University of New South Wales, 2014. eBook, ProQuest eBook Central.

NASA. “Voyager: The Interstellar Mission”. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute ofTechnology. http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/

Nelson, Stephanie, and Larry Polansky. “The Music of the Voyager Golden Record”. Journal of Applied Communication Research. November 1993.

Pinkard, Ryan. “Dark Was the Night: The Legacy of Blind Willie Johnson”. Tidal. February 26, 2016. http://read.tidal.com/article/dark-was-the-night-the-legacy-of-blind-willie-johnson share

Sahlins, Marshall. “The Original Affluent Society”. From Man the Hunter. 1966. Accessed online: http://www.luminist.org/archives/Sahlins_original.htm

Image credit: NASA. Originally, they can be found here and here.

Thank you to Gray Livingston for reviewing my work and offering helpful advice on how to make it better.