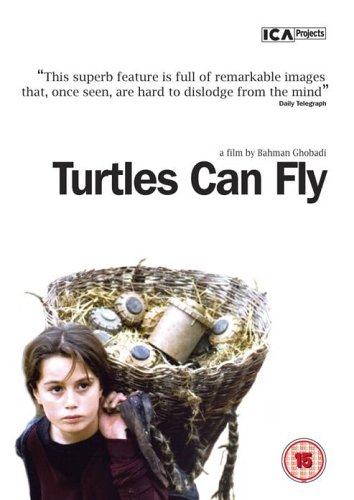

In the eighth grade I was introduced to the most horrifying film I have ever seen. I am no expert critic of horror or drama film. As a person who considers herself a fan of both genres, however, and as someone who has seen innumerable films of both types, I can say with confidence that no film left me more disturbed than Kurdish Bahman Ghobadi’s 2004 movie “Turtles Can Fly.” Its plot could be best described as every parent’s nightmare, with hundreds of orphaned children living in an impoverished war territory. Picture the tragedy of a movie like “The Boy in Striped Pajamas”, but multiplied and compounded by dozens instances of children in distress. I am talking about a movie that’s effects on the viewer are hundred times more heartbreaking, and infinitely more traumatic. So traumatic, in fact, that 8th-grade-me, along with many of the friends I watched with, had to watch multiple episodes of Modern Family right after finishing “Turtles Can Fly” to prevent sudden teary outbreaks at any point later that day. Yet, in a movie that appears to be so dystopian, expressing the horrors experienced by the Kurdish children living in Iraq near the Turkish border, Ghobadi decided to include certain events that express themes inconsistent with the mood of the rest of the film. That is, throughout the film, it appears that there are glimpses of what might be considered by some, a utopia.

Symbols representing traditionally considered virtues or of positive utopian notions contrast with the scenes they lay in. “The red fish”, for example, representing a beacon of hope, is a spot of color in a world of grey and reminds us of the beauty still left in the world. In the film it seems a bit out of place as it appears after a scene about how three children drowned looking for said fish, and is followed by an unhappy young girl running off home from the river to deliver water to what is left of her family. Or for example, a scene where a boy’s leg being blown off by a land mine contrasts with the symbolism of an arm broken off a Saddam Hussein statue, representing the breaking away from the oppression of Hussein and the beginning of a revolution that potentially could lead to peace.

( Watch: 1:21:30- 1:23:05)

Making the argument that this film has an utopian aspect based off these few symbols is a bold position. The waves of positivity from these symbols, however, is reinforced by various random yet significant acts of kindness and perseverance scattered throughout the film. In the town where the movie was filmed, everyone is equally poor and living in the same fear that any day the town can be attacked and and life would end, yet everyone keeps relatively calm and works together to make the most of the situation. Surprisingly enough, even the children become equal to adults as they take on many adult jobs like mine defusing, bartering for satellites and guns in a nearby town’s marketplace, gas mask distribution, or for one of our protagonist, managing large bodies of people to complete such tasks.

In addition to this unity of young and old coming together to create a better environment, there is an overall embrace of the disabled members of the community, another surprising silver lining to the horrors displayed in the film. There are scenes where one’s disability is used as an insult, but for the most part these disabled people work and are treated as everyone else. In fact, the managing protagonist even goes out of his way to make amends with another protagonist, an armless protagonist, that he has had previous quarrels with. While the manager may not be a fan of the armless boy, he puts his personal issues aside and tries to keep his composure to maintain peace. The crippled protagonist also offer’s some examples of kindness, as he goes out of his way to make sure that his own sister does not do anything to harm of her child (that, I should mention, was a result of a rape by a member of band of guerrilla fighters that came to their town.) In addition, in between scenes of our managing protagonist screaming at children working, and quarrels (sometimes ending in a bloody nose) between the two male protagonists, the crippled boy offers help to the managing kid, just to benefit the greater good and safety of all people.

These two aspects, along with some reoccurring positive references to America, combine to point to a central beacon of utopian hope: American Intervention. Following a scene where our single female protagonist, the sister of our crippled protagonist, has a flashback to the night she was sexually assaulted, there is a scene of hundreds of people gathering on a hill to have American helicopters fly overhead and drop flyers with phrases like “It’s the end of injustice, misfortune, and hardship.” and “We will make this country a paradise.” This scene of America-provided inspiration to carry on fighting through the town’s harsh life is followed by the image of a group of kids going to a marketplace to try and buy machine guns with land mines (AMERICAN lands mines to be precise).

(Watch: 1:00:25-1:00:50)

These faint moments of lighthearted kindness, subtle compassion, and lingering hope can most obviously be justified as being placed to relieve the audience from the heavy stress of the movie. Yet, this idea backfires against itself. The “optimistic” moments in the movie juxtapose with how heavy and distressful the rest of the movie is. It can be argued, in fact, that these moments accomplish the exact opposite of what initial role one may think they have. In these scenes it appears that just as we, the audience, begin to become desensitized to the tragedy expressed, we are provided with a moment of hopeful light , just to be then thrusted back into the tragedy, once again needing to readjust to the heavy material.

Why would Ghobadi, or any director like Mark Herman of “The Boy In Striped Pajamas”, try to bring about this ridiculous emotional-rollercoaster inducing glimpses of optimism into a movie about such a somber subject? What we get is a heightened desire for a perfect world through these things, also known as a desire for “utopia.” Utopia is a term that has been defined differently by philosophers and writers alike. There are different ideas as to what a utopia should or does encompass, and as this movie’s protagonists and plot revolve around children, it is apparent the utopia here, whether to appeal to adults with kids, or to kids themselves, puts focus towards providing children with stability, peace, and the ability to enjoy childhood, without having to deal with mature problems.

Utopia does not end there, at least not for this movie. It would not seem right to say that a movie like “Turtles Can Fly” is flat out utopian. The idea of utopia is ingrained deeper into the movie than that. With its plot rooted in Kurdish,Turkish, and Iranian history, intwined with glimpses of relationships between The United States and various Middle Eastern groups, and as hopeless as the end seems, this films intentions are not any different from some more popular and more openly utopian films such as “Hotel Rwanda” or “Peter Pan”. What is special about Ghobadi’s work is that it is approaches utopia in a non-conventional way. “Turtles Can Fly”’s goal is not to provide us with a potential utopia, but to make the viewer realize how badly you want the sort of utopia it hints at. The juxtaposition between a perfect world, and the cruel realistic setting depicted in the movie provides a heightened desire for a utopia, especially for children. After accepting this notion that the movie serves to introduce utopia via juxtaposition, the context of the scenes mentioned above become more clear. In scenes like that of where the managing protagonist shows some compassion to the crippled protagonist, wedged between shots of abandonment of young children and attempts at suicide, it is apparent that the positioning of compassion between young children between scenes depicting neglect is a conscious and carefully executed decision to strengthen the effect of appeal of utopian themes.

Naturally, in any movie with a few optimistic scenes sprinkled across heavily saddening content to emphasize utopianism, the question of why the film is not just called dystopian will arise. That of course is a logical conclusion to come to. Thomas Halper and Douglas Muzzio provide a description for dystopian based media that seems to encompass what “Turtles Can Fly” is. They write, “Like utopias, dystopias critique contemporary society; but unlike utopias, dystopias offer not a hopeful vision of what ought to be but an angry or despairing picture of where we are said to be headed—or perhaps (though we may not know it) where we already are.”(Halper and Muzzio 381) It is easy to interpret the film as dystopian, especially based on Halper’s and Muzzio’s description. But to suggest that dystopia and utopia are mutually exclusive in every aspect does not float well with a film such as the one at hand. Yes, the film is not utopian in the way that it has a happy ending, or provides a glimpse in to an alternate reality better than what we have now, but it is utopian in the emotion it elicits from the viewer. In some ways, I may even suggest that the movie is so dystopian that it reinforces the lack of the desired aspects of utopianism. Seeing the dystopia of “Turtles Can Fly” gears toward extracting our desire to achieve utopia and bring it to the characters in the film. Films provide a means of escape from daily life. What better way to encourage escapism than to create a completely anti-utopian movie and show the potential or current horrors of our world. It makes the audience thirsty for social justice.

Why does it matter than the film has utopian motivations or not, or what even is the reason for adding utopia into a film at all? That can all be attributed what has become of pop-culture that is, to fulfill the natural tendency of pop-culture to push us towards an ideology. In the case of “Turtles Can Fly” the ideology is hinted through various symbols, like, as listed earlier, the red fish and the Saddam Hussein statue’s arm. Both these things, framed with highly anti-utopian scenes, suggest the theme of a hope for an improved future and the fall of oppression and instability. In fact with further analysis, these symbols, especially the arm of the Saddam Hussein’s statue, paired with the scenes of The United States as a savior during some of the darkest portions of the film, appear to suggest that an improved future and the fall of oppression may have something to do with America’s help. Not to suggest this is the only ideology implied in the film, as its plot and history is more complicated than can be addressed in a short time, but the film appears to be propaganda advocating pro-American ideologies. To accomplish such advocation effectively, a sense of utopia must be tied in with the ideology. Ideology virtually runs on utopia, as utopia is what can make an ideology attractive to people. As put by Fredric Jameson, “…the hypothesis is that the works of mass culture cannot be ideological without at one and the same time being implicitly or explicitly Utopian as well: they cannot manipulate unless they offer some genuine shred of content as a fantasy bribe to the public about to be so manipulated.”(Jameson 144)

Do you enjoy seeing children collect mines, practice shooting guns, have to wear gas masks in fear of being attacked? The movie is not even set in the United States, yet I, as a “viewer” of the film can attest to having my emotions personal affected by the events observed in the film. Why is there still a pain felt while watching the movie? It is because the movie is geared toward bringing out the little voice (some call it the conscious) in every rational and moral person’s head. Naturally people crave a perfect society, a utopia. What better way to express an ideology, be it an actually message or theme or even the just the desire for people to consume more film, than to bribe people with insights to utopia. The film is incredibly complicated, and to try to weed out every aspect of each ideology it suggests, and every glimmer of utopian themes it may include, would take hundreds of pages of analysis. But superficially, even a basic analysis such as the one above can reveal the power of utopian themes to support and strengthen the desire to adopt the ideologies intended on spreading throughout the movie.

(Watch: 1:13:45-1:16:45)

Sources:

1. Halper, Thomas and Douglas Muzzio. “Hobbes in the City: Urban Dystopias in American Movies.” The Journal of American Culture 30 (2007): 379-390. PDF

2. Jameson, Fredric. “Reification and Utopia in Mass Culture”. Social Text 1 (1979): 130–148. Web.