The book, Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation, by Mary Daly. Published in 1973.

In 1973, Mary Daly, an American radical feminist theologian, philosopher and ethicist (Stefon), released Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation. Because of Daly’s radical approach, many women rejected her ideas while accepting them as new spiritual ideas. In this book, Mary Daly challenges the Christian doctrine and suggests that Christianity has manifested itself as a symbol for the patriarchy and an enabler of misogyny. Daly’s radicalism prompts her to outright reject Judeo-Christian, Roman Catholic and Protestant religions. Her critiques of these traditional religions lead into her argument that women’s religiosity and spirituality must come from within oneself and not be dependent on a male figure. In her book, she argues that “the women’s revolution, insofar as it is true to its own essential dynamics, is an ontological, spiritual revolution, pointing beyond the idolatries of sexist society and sparking creative action in and toward transcendence” (Daly 6). She emphasizes that “the liberation of language is rooted in the liberation of ourselves” (Daly 8). Creating spaces that help women become comfortable with expressing themselves results in the societal and spiritual liberation of women. It breaks the chains of the patriarchy and allows for women to recognize their own sense of power and participate in new theologies and philosophies. Not only does Daly believe that women’s literary works are a form of liberation, but she views the women’s movement as a form of “cosmic covenant” that may transform sexist society as she draws similarities between prophets and women in the movement. She affirms that, “…prophets have been persons who do not receive their mission from any human agency, but seize it. The revolution of women has this kind of dynamic…what we are ‘seizing’ and ‘usurping’ is that which is rightfully and ontologically ours – our own identity that was robbed from us and the power to externalize this in a new naming reality” (Daly 164). The Women’s Liberation Movement offered opportunities that allowed women to reclaim their feminine identities and redefine their realities through different spiritual and religious beliefs.

Among the critiques of this book, Audre Lorde published a letter to Mary Daly expressing how the book has been “strengthening and helpful” (Lorde) to her in her perception of Eurocentric religions. Carol Anne Douglas also provided her opinion on Daly’s book in the second issue of the fourth volume of Off Our Backs. She summarizes Daly’s arguments and provides her own opinion on Daly’s radical views on the women’s movement as a form of female transcendence. As a feminist writer, Douglas’s critiques Daly’s argument by addressing that “One problem with Daly’s perception of feminism as a religious revelation is that feels it must have a message for men some day too; separatism can only be a temporary means of self-strengthening (even if it is a necessary temporary step) rather than a goal” (Douglas). This critique implies that Douglas must want the message to only be available to women as it can create a form of feminine power that rejects any traces of men who may abuse this power. She agrees with and praises Daly’s perspectives on the women’s movement and regards her philosophies “cogent and exciting.” Which in turn provides the audience of Off Our Backs an opportunity to understand Daly’s points and internalize these arguments to redefine their relationship with religion as feminists.

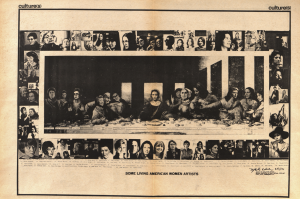

Within this same issue of Off Our Backs, Mary Beth Edelson depicts different women who have contributed to the women’s movement through art like Louise Bourgeois, Lee Krasner and Georgia O’Keeffe in a picture of the Last Supper by Leonardo Davinci. By replacing the faces of Jesus and his disciples with the faces of women, Edelson

A picture created by Mary Beth Edelson as it appears in the second issue of the fourth volume of Off Our Backs.

displays the transformation of religion that Mary Daly advocated for in Beyond God The Father. The redefinition of religion encouraged women to interpret religious texts under the lens of feminism as well as stray away from male-centered religions and prioritize women as equal human beings.

By outwardly rejecting the Christian doctrine, Daly helps women realize that by reconstructing religion to prioritize their identities and fit their wants and needs the women’s movement is further empowered. The radical viewpoints that Mary Daly makes in her book creates a new perception of the women’s movement as a religious revelation that is spearheaded by women’s literary and creative works. The shift towards female spirituality and religiosity revitalizes the power of women and transcends male-centered religions.

Sources:

Daly, Mary. Beyond God the Father: Toward a Philosophy of Women’s Liberation. United States, Beacon Press, 1985. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Beyond_God_the_Father/tswJvbG9mAQC?hl=en&gbpv

Fannie Lou Hamer, et al. Off Our Backs, vol. 4, no. 2, Jan. 1974, pp. 1–20, https://jstor.org/stable/community.28041805.

Lorde, Audre. “An Open Letter to Mary Daly: Audre Lorde (1979).” History Is a Weapon, https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/lordeopenlettertomarydaly.html.