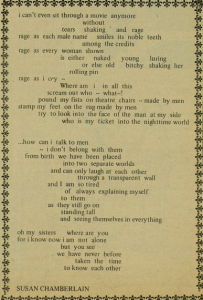

The violence that women endured cannot and will not be rationalized for any reason; however, it is worthy to note the sisterhood that women’s writing of abuse yielded. For example, Susan Chamberlain writes an untitled poem that can be found in the second issue of Everywoman, in which she expresses her desire to get to know the women around her. She feels trapped by men’s ability to assert their dominance over women, and how their dominance is constantly being reinforced. This is apparent in the lines that read, “stamp my feet on the rug made by men / try to look into the face of the man at my side / who is my ticket into the nighttime world” (Chamberlain 14-16). Although not specifically mentioning instances of abuse, readers can grasp the internalized struggle that the writer is facing; her existence in this world is characterized by the fact that she is a woman, and she can only hold a sense of security in public when in the presence of a man. At the end of the poem, Chamberlain expresses her desire to develop a sense of sisterhood with the women around her by writing, “oh my sisters where are you / for i know now i am not alone / but you see / we have never before / taken the time / to know each other” (29-34). These lines encourage women to express themselves and find support in one another, in efforts to dismantle the consistently reinforced patriarchal society that they reside in.

Untitled poem by Susan Chamberlain found in Everywoman vol. 1 no. 2.

The encouragement that Chamberlain provides to women in regards to getting to know one another’s stories holds applications to domestic violence. This means that society must be cognizant of its role in maintaining the power dynamic that exists within one’s home, since an unspoken rule that “what happens in one’s home stays in one’s home” exists. Women must absolve themselves from the guilt that they hold in regards to speaking out about abuse, and come to the conclusion that they will never be the reason for men’s domineering actions. That is, it was encouraged during Second Wave Feminism to abolish the notion that family matters are inherently private matters. Instead, by expressing the complexity of victimhood in the form of writing, women were able to unite and realize the extent to which they could combat the epidemic of domestic violence. In Off Our Backs, a popular feminist periodical, Douglas embodies the complexity of women’s victimhood in writing,

When one has been a feminist for a certain amount of time, she sometimes no longer wants to think of women as victims. Being a victim sounds like being passive, unrebellious, pre-feminist, etc. Of course, we must try to become strong, but whatever individual strength we develop will not change our status as an oppressed group. To disassociate ourselves from women who have been victimized, to imagine that they are somehow different from us, is to accept the idea that they have chosen their oppression instead of having it thrust upon them. We are all vulnerable, we can all be victimized; we can only reject that victimization together. […] When they hit one of us, they hit us all. (Douglas et al. 4-5)

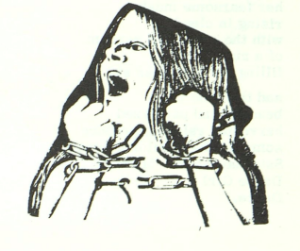

During Second Wave Feminism, women were encouraged to break free from the chains that restrained them and instead seek unity with their sisters.

An image of a woman breaking free from chains, featured in Women: A Journal of Liberation vol. 3 no. 2.

Sources:

Chamberlain, Susan. Everywoman vol. 1, no. 2, 29 May 1970, p. 6.

Douglas, Carol, et al. “Battered Wives Make Us Feel Beaten.” Off Our Backs vol. 6, no. 9, December 1976, p. 4-5.

Everywoman vol. 1, no. 2, 29 May 1970.

Off Our Backs vol. 6, no. 9, December 1976.

Women: A Journal of Liberation vol. 3, no. 2, 1 January 1972.

Women: A Journal of Liberation vol. 6, no. 2, 1 January 1975.