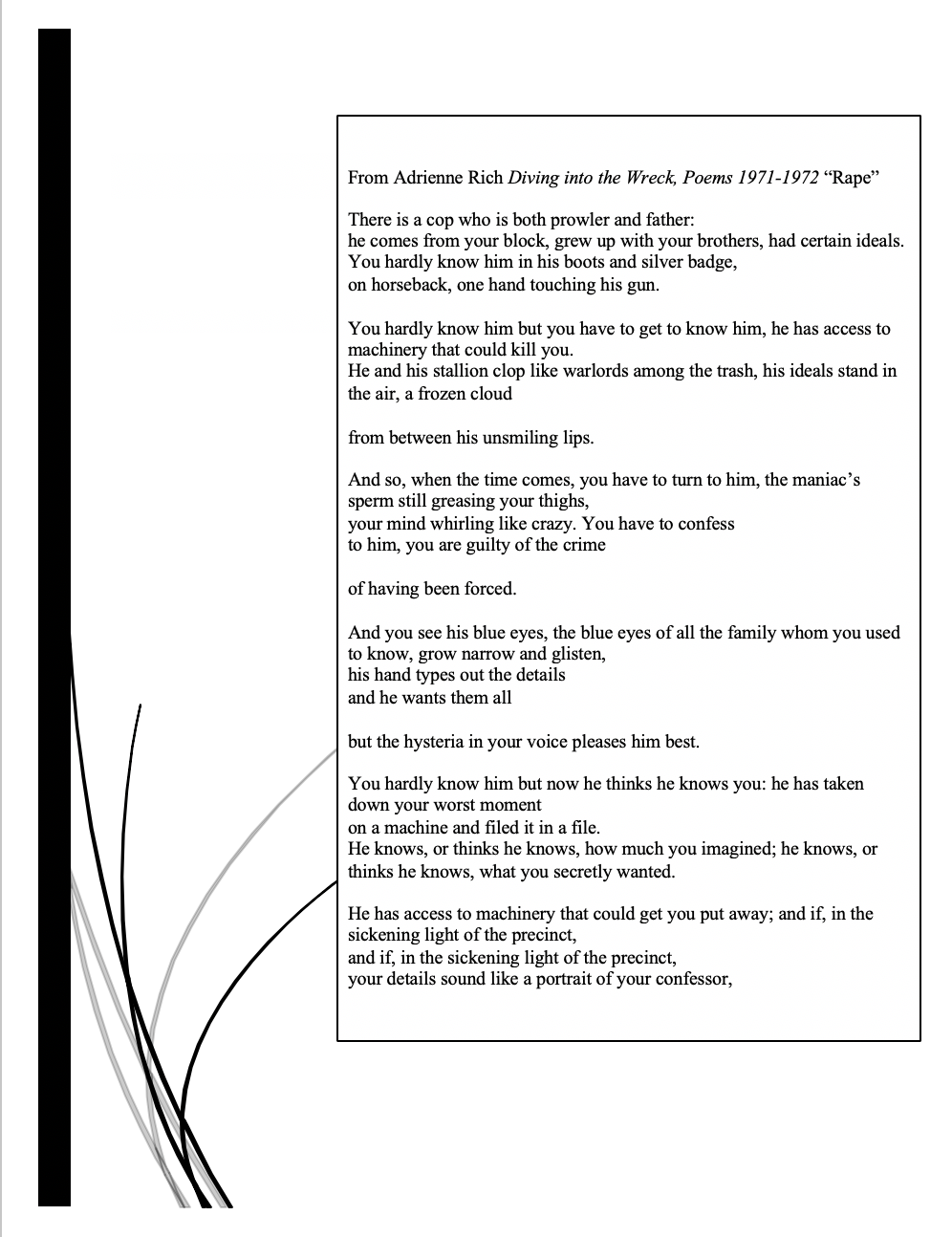

“Rape” by Adrienne Rich

Image of Adrienne RIch from the New Yorker

One of the most influential books published during the Second Wave was Adrienne Rich’s collection of poetry Diving into the Wreck. In “Rape,” one of the key poems in this collection, Rich tells the story of a woman recounting the details of her recent rape to a policeman. This story takes place in the early 1970’s, in an era when men scoffed at women who claimed they were raped and would often accuse them of adultery. Even the woman in Rich’s poem knew that because of the policeman’s pre-judgments, she would be found “guilty of the crime / of having been forced” (Rich, lines 14-5). Through breaks in repetition and opposing descriptions, Rich conveys an image of hierarchy that displays the disturbing reality that the victims of rape are themselves treated as criminals.

The line, “he has access to machinery that could kill you,” (Rich, line 7) places “he” as the subject of the independent clause, “you” as the direct object of the adjectival dependent clause, describing “machinery.” Sovereignty belongs to the subject noun in any clause, but supreme power belongs to the subject that reigns over the independent clause. Adjectival dependent clauses act in service to the noun or pronoun they describe. In line seven, the clause “that could kill you” is the humble servant to “machinery.” This along with the fact that “machinery” functions as nothing more than a lowly object of the preposition, forces “you,” the inferior noun in the dependent clause, to the bottom of the totem pole. “You” is powerless. Even line seven’s syntax alone explains that “you,” the rape survivor, exists in a state of the complete and total mercy to “he,” a police officer, the man. In this way, Rich employs syntactic hierarchy to express the reality of the situation. “To him” (Rich, line 14) stars line 14. Even though “to him” is a mere adverbial prepositional phrase, its physical placement at the front of a line, gives it power. “You have to confess” (Rich, line 13) may be the core of the sentence, but because it lies buried at line thirteen’s end and because of the enjambment, line thirteen has a less definitive tone. Syntactically, “you” should be the sentence’s focus. Truly, Rich argues, the rape victim should be the focus and her will should be justly served, yet, once again, the male figure denies her that right. The male figure steals power. His will, the will of the patriarchy, is served by the female in the end. Rich presents the entire story in an experiential way and uses second person point of view to augment the potency behind these demonstrations of power. Once line two introduces the possessive pronoun “your,” all that follows put the reader directly into story. Whatever happens to “you,” the injustice, the subjugation, effects the reader on a more personal level; thus, the reader tends to pay more attention to declarative sentences and tends to feel more demand from imperative sentences.

“Rape” poem by Adrienne Rich

Rich employs parallelism and repetition to illustrate structure, which she proceeds to break in order to express the wrongfulness about the patriarchy’s criminalization of rape victims. Rich utilizes this technique first in lines two and three, “he comes from your block, grew-up with your brothers, / had certain ideals” (Rich, lines 2-3). The first two verb phrases mirror each other. Both lines follow the pattern transitive verb, preposition, possessive pronoun, object of the preposition. Both lines end with the same possessive pronoun and a word that begins with the letter “b.” Line three breaks this parallelism. Not only does “had certain ideals” (Rich, line 3) stand apart poetically but, due to its placement on a separate line, “had certain ideals” stands apart physically as well. Rich, creates this separation for two reasons. Fist, whereas the first two lines include an element each that the rape victim shares, line three does not possess such an element. This emphasizes the simple, though crucial, point that the rape victim does not share “his ideals.” Second, Rich uses this separation to highlight the great significance behind the man’s “certain ideals.” Line three is the shortest line in the entire poem, for it is the preface for what is to come. “Had certain ideals” foreshadows that those ideals will play a critical role in the lines to follow. In the end, it is because of the man’s “ideals” that the poem later states “he thinks he knows you […] He knows, or thinks he knows, how much you imagined; / he knows, or thinks he knows, what you secretly wanted,” (Rich, lines 21, 24-5) metanoia correcting “he knows” to “thinks he knows” in order to underscore the word “thinks.” It is because of the man’s “ideals” that he prejudged the person before him and “thinks” she is the criminal. It is because of the man’s “ideals” that no matter what the rape victim says or does or argues or proves, she will be condemned by the law. “His blue eyes,” (Rich, line 16) is further defined in the appositive as “the blue eyes of all the family / whom you used to know,” (Rich, line 16-7). Anadiplosis connects the single policeman to “all” through the repetition of “blue eyes.” It is just the eyes of the police officer that look at the woman with condemnation and apathy. It is the eyes of everyone. Everyone, her entire society, looks at her who was raped with condemnation and apathy. The only word for word repetition that Rich never shifts or breaks occurs at the end of the poem, “and if, in the sickening light of the precinct” (Rich, line 27 and line 28). All repetition and parallelism until then possessed some qualifying feature or further distinction. Lines twenty-seven and twenty-eight do not, for unlike the others, Rich presents these lines as an unbreakable truth.

Picture of Adrienne Rich

The everlasting truth resides in the word “sickening” and in the way that the parenthetical “in the sickening light of the precinct” interrupts “and if, […] / your details sound like a portrait of your confessor” (Rich, lines 28-9). Throughout the poem, Rich presents various claims about the unjust nature of the patriarchy, and as she makes each argument, she provides slight glimmers of hope that change is possible. Until Rich describes the sick feeling that interrupts the woman’s thoughts when she confronts an institution made to protect mankind, an institution made to condemn womankind. Even if the women changed the officer’s “certain ideals,” (Rich, line 3) even if the woman got “to know him,” (Rich, line 6) even if the woman convinced him of her innocence, her feelings towards the institution she faces and the way such feelings interrupt her thoughts would never change.

To solidify the image of the rape victim’s powerlessness against the authority that wrongs her, Rich makes intentional diction choices to describe the two characters present in the scene. While the police officer’s description cloaks him in tainted power, the woman is left naked by comparison. Blatant opposition occurs in line one when Rich uses the predicate nominatives “prowler and father” (Rich, line 1) to define the cop. The word “prowler” evokes the image of a bestial creature that prowls in night looking for prey or something to steal. A “prowler” is untrustworthy. The word “father,” however, is meant to represent a man who acts the leader and protector of his home and children. A “father” should be trustworthy. Unnerving slant rhyme is the only similarity between these two descriptions. Rich employs these two words to expose the hypocritic nature of the cop’s identity and to begin illuminating the woman’s helplessness in comparison. The reference to the cop being “in” a “silver badge” (Rich, line 4) is a form of metonymy that represents a “police uniform.” The metallic badge functions as subtle reminder that the one who stands before the woman is not a man but a cog in a great and terrible machine. This slight reference to the cop’s position within the machine makes the woman appear even weaker, for, the cop belongs to that same machine that Rich alludes to on line twelve. Line twelve describes the woman as having “the maniac’s sperm still greasing [her] thighs” (Rich, line 12).  “Greasing” is a metaphor in itself. The connection between “sperm” and “grease” illuminates the intentionality behind the word “maniac” appearing so similar to “mechanic.” The man who raped her also belongs to that great and terrible machine, the patriarchy. Imagery in the fifth line of the cop being “on horseback” (Rich, line 5) stages the cop as seated above the rape victim. The cop looks down upon her. This physical depiction joined with the simile in line eight, “like warlords,” (Rich, line 8) paints a portrait of the officer’s tyrannical power. “Among trash” (Rich, line 8) continues the imagery. All else in the portrait is depicted as garbage beneath the stallion’s feet; hence, the rape victim is garbage too. These descriptions position the officer and the girl on polar opposite ends of the power spectrum.

“Greasing” is a metaphor in itself. The connection between “sperm” and “grease” illuminates the intentionality behind the word “maniac” appearing so similar to “mechanic.” The man who raped her also belongs to that great and terrible machine, the patriarchy. Imagery in the fifth line of the cop being “on horseback” (Rich, line 5) stages the cop as seated above the rape victim. The cop looks down upon her. This physical depiction joined with the simile in line eight, “like warlords,” (Rich, line 8) paints a portrait of the officer’s tyrannical power. “Among trash” (Rich, line 8) continues the imagery. All else in the portrait is depicted as garbage beneath the stallion’s feet; hence, the rape victim is garbage too. These descriptions position the officer and the girl on polar opposite ends of the power spectrum.

In the 1970’s, men and women usually inhabited opposing ends of the spectrum, but society back then deemed raped women the lowliest of all.

Sources:

Rich, Adrienne. Diving into the Wreck: Poems, 1971-1972. 1st ed. New York: Norton, 1973. Print.