Chicana Feminists were continually confronted by the fact that they did not fit Euro-centric beauty standards. This phenomenon was not exclusive to only Chicanas; it was something felt a nd recognized by several minority women. The editors of Heresies, Third World Women: the politics of being other, discuss in detail the sentiments of the label other. This label created an inferiority complex among these minority women. Katherine Hall’s drawing “The Alien,” published in this 1979 Heresies issue, along with Inés Hernández’s “To Other Women Who Were Ugly Once,” published in Infinite Divisions in 1993, illustrate the dialogue of minority beauty standards.

nd recognized by several minority women. The editors of Heresies, Third World Women: the politics of being other, discuss in detail the sentiments of the label other. This label created an inferiority complex among these minority women. Katherine Hall’s drawing “The Alien,” published in this 1979 Heresies issue, along with Inés Hernández’s “To Other Women Who Were Ugly Once,” published in Infinite Divisions in 1993, illustrate the dialogue of minority beauty standards.

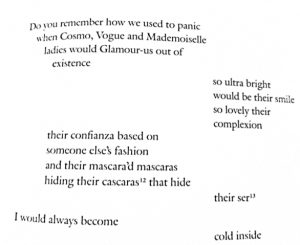

Hernández starts off the poem in a humorous tone: “Do you remember how we used to panic.” The poet wants the reader to understand the absurdity of these inferior feelings. These Chicanas recognized that the models on these fashion magazines were inauthentic; they hide the women from their true “ser”/self. Why must Chicanas try to conform to these beauty s tandards that hide the authentic person behind the make-up? Hernández states, “Que mataonda,” what a drag to need to constantly fit into a model that is not yourself. The poet claims “resistance to this type of existence.” This is not a way to live. The ending of the poem calls for the embrace of the “natural luz,” the natural appearance, as opposed to the artificial one presented in magazines. .There is an acceptance of one’s appearance despite its contrast to mainstream ideals; this is commonly expressed as “Brown is Beautiful” and is not exclusive to Chicanas. As one can see, while the drawing represents the sentiments of inferiority common to minority women, once it is viewed alongside Hernández’s poem, one begins to sense the development of Chicana confidence.

tandards that hide the authentic person behind the make-up? Hernández states, “Que mataonda,” what a drag to need to constantly fit into a model that is not yourself. The poet claims “resistance to this type of existence.” This is not a way to live. The ending of the poem calls for the embrace of the “natural luz,” the natural appearance, as opposed to the artificial one presented in magazines. .There is an acceptance of one’s appearance despite its contrast to mainstream ideals; this is commonly expressed as “Brown is Beautiful” and is not exclusive to Chicanas. As one can see, while the drawing represents the sentiments of inferiority common to minority women, once it is viewed alongside Hernández’s poem, one begins to sense the development of Chicana confidence.

In the same period as Katherine’s Hall drawing and the release of Infinite Divisions, Selena Quintanilla-Perez, a Mexican-American singer, rose to stardom.  Growing up in Corpus Christi, Texas, Selena became involved in music through the guidance of her father (Corpus). Her first debut was in the early 1980s as a member of “Selena y Los Dinos” (Corpus). As she garnered fame, Selena became known as the Queen of Tejano Music (Corpus). While her life was tragically cut short at age twenty-three in March of 1995, her influence still lingers. Despite the gap of years from Selena’s rise to fame and my own adolescence, Selena’s story is very personal to me. Representation is essential. Growing up, Selena solidified the message of “Brown is Beautiful” for me. I did not feel the need to struggle to conform to look like the women found on the cover of Cosmo or Vogue magazines. Not only did Selena provide me with the confidence to be proud of how I looked, she also helped bridge the gap between my “American” self and my “Mexican” self–a binary that has been frequently discussed within poetry by early Chicana Feminists. As a child, I tried to assimilate into “American” culture and shed my Mexican heritage. By listening to Selena, I was able to practice my Spanish and reconnect with an identity that I had lost. As Chicanas continue to seek representation in all platforms moving forward, their mere presence in these spaces will inspire young girls like myself to strive for futures that seemed previously unattainable for a Chicana.

Growing up in Corpus Christi, Texas, Selena became involved in music through the guidance of her father (Corpus). Her first debut was in the early 1980s as a member of “Selena y Los Dinos” (Corpus). As she garnered fame, Selena became known as the Queen of Tejano Music (Corpus). While her life was tragically cut short at age twenty-three in March of 1995, her influence still lingers. Despite the gap of years from Selena’s rise to fame and my own adolescence, Selena’s story is very personal to me. Representation is essential. Growing up, Selena solidified the message of “Brown is Beautiful” for me. I did not feel the need to struggle to conform to look like the women found on the cover of Cosmo or Vogue magazines. Not only did Selena provide me with the confidence to be proud of how I looked, she also helped bridge the gap between my “American” self and my “Mexican” self–a binary that has been frequently discussed within poetry by early Chicana Feminists. As a child, I tried to assimilate into “American” culture and shed my Mexican heritage. By listening to Selena, I was able to practice my Spanish and reconnect with an identity that I had lost. As Chicanas continue to seek representation in all platforms moving forward, their mere presence in these spaces will inspire young girls like myself to strive for futures that seemed previously unattainable for a Chicana.

Sources:

Hall, Katherine. The Alien. 1979. Heresies: A Feminist Publication of Art & Politics. Edited by Sue Heinemann, vol. 2, issue 4, Heresies Collective, 1979.

Hernández, Inés. “To Other Women Who Were Ugly Once.” Infinite Divisions: An Anthology of Chicana Literature. Edited by Tey Diana Rebolledo and Eliana S. Rivero, University of ArizonaPress, 1993.

Portillo, Lourdes, et al. Corpus. Women Make Movies, 2018.