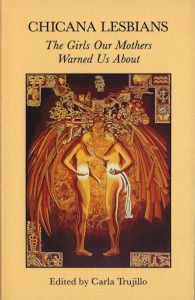

Chicana Lesbians: The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About, published by the Third Woman Press in 1991, features works of poetry that indicate the widespread homophobia within the Chicano Community as well as within ma instream Anglo society. Norma Alarcon founded the Third Woman Press in 1979 as a platform for queer and feminists of color to be heard in the Second Wave Feminist Movement. Alarcon states she was inspired to create this publishing company once she realized “there weren’t enough women of color or Latinas… for me to have a conversation with” (Cockrell, “A Labor of Love”). Chicana sexuality was not an issue that was discussed within nor outside the household. Life was dictated largely by traditional gender roles and religion that left little to zero tolerance for any deviations from the norm: “For the lesbian of color, the ultimate rebellion she can make against her native culture is through her sexual behavior. She goes against two moral prohibitions: sexuality and homosexuality” (Anzaldúa 19). The following three excerpts of the poems below by Gina Montoya, Natashia Lopez, and Juanita M Sánchez, featured in Chicana Lesbians, illustrate three different perspectives on living as Chicana Lesbians.

instream Anglo society. Norma Alarcon founded the Third Woman Press in 1979 as a platform for queer and feminists of color to be heard in the Second Wave Feminist Movement. Alarcon states she was inspired to create this publishing company once she realized “there weren’t enough women of color or Latinas… for me to have a conversation with” (Cockrell, “A Labor of Love”). Chicana sexuality was not an issue that was discussed within nor outside the household. Life was dictated largely by traditional gender roles and religion that left little to zero tolerance for any deviations from the norm: “For the lesbian of color, the ultimate rebellion she can make against her native culture is through her sexual behavior. She goes against two moral prohibitions: sexuality and homosexuality” (Anzaldúa 19). The following three excerpts of the poems below by Gina Montoya, Natashia Lopez, and Juanita M Sánchez, featured in Chicana Lesbians, illustrate three different perspectives on living as Chicana Lesbians.

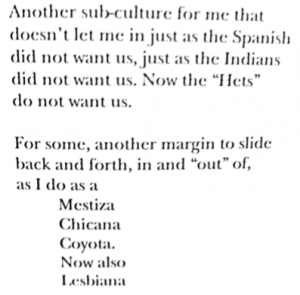

Gina Montoya’s “Baby Dykes” details her struggle to identify with other lesbians. Montoya begins the poem by stating, “How many years of oppression must / there be to be considered trust / worthy in Lesbian culture and lifestyle?” Being lesbian is “another sub-culture” where she finds herself struggling to fit in. To Montoya, her sexuality is yet another label such as Mestiza or Chicana that she “slide[s] back and forth [between].” Despite her sexuality being one of her dominant attributes and  the subsequent marginalization that accompanies it, Montoya is frustrated that she does not have her own place within this community. The stanza following the excerpt on the left begins, “Learning a new language: Lesbian” and continues listing the languages that Montoya has to learn: Lesbian, English, Spanish, and Spanglish. By using words such as learning and language, Montoya implies how foreign this culture surrounding her sexuality is. By listing off the “different languages,” Montoya shows the reader the multitude of her identities. She is not solely lesbian nor Mexican. She is in a constant flux of identities as they play different roles in her life.

the subsequent marginalization that accompanies it, Montoya is frustrated that she does not have her own place within this community. The stanza following the excerpt on the left begins, “Learning a new language: Lesbian” and continues listing the languages that Montoya has to learn: Lesbian, English, Spanish, and Spanglish. By using words such as learning and language, Montoya implies how foreign this culture surrounding her sexuality is. By listing off the “different languages,” Montoya shows the reader the multitude of her identities. She is not solely lesbian nor Mexican. She is in a constant flux of identities as they play different roles in her life.

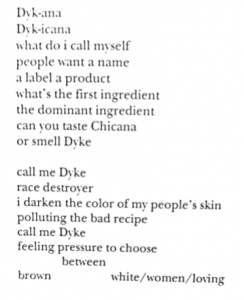

Natashia Lopez’s “Trying to be Dyke and Chicana” attempts to reconcile both Chicana and lesbian identity into one. In the following excerpt from the beginning of the poem,  the reader can see Lopez wrestle with combining these two attributes of her identity. In the end, Lopez coins the term “Chyk-ana” to summarize herself. But this term and unconditional acceptance of self is not easy, Lopez struggles to identify the dominant attribute of her identity: “what do I call myself…what’s the first ingredient / the dominant ingredient.” Lopez also illustrates the widespread homophobia within her community: “race destroyer / I darken the color of my people’s skin.” Shame and anger are implicit within these lines as Chicana Lesbians were degraded even within their own ethnic community.

the reader can see Lopez wrestle with combining these two attributes of her identity. In the end, Lopez coins the term “Chyk-ana” to summarize herself. But this term and unconditional acceptance of self is not easy, Lopez struggles to identify the dominant attribute of her identity: “what do I call myself…what’s the first ingredient / the dominant ingredient.” Lopez also illustrates the widespread homophobia within her community: “race destroyer / I darken the color of my people’s skin.” Shame and anger are implicit within these lines as Chicana Lesbians were degraded even within their own ethnic community.

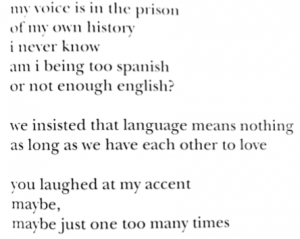

Juanita M Sánchez’s “Voz en una carcel” incorporates her sexuality in a slightly different manner than the previous two poets. While Montoya and Lopez focus heavily on their sexuality, Sánchez illustrates how her sexuality affects another aspect of her identity–the binary of being Mexican-American. “Voz en una carcel” reads as a love poem to Sánchez’s Anglo-American lover. Preceding the excerpt below, Sanchez states,  “you keep to your language / while I struggle to understand…wanting to see your acceptance / behind the round blue eyes.” Based on this description, we can infer that her lover is white with blue eyes. Sanchez struggles with the language barrier and her Mexican heritage in an assimilationist environment: “am I being too Spanish / or not enough English?” Then, Sanchez ends the poem with a hint of suspicion towards her lover and expresses her vulnerability as being perceived as not American enough. Love does not seem to mitigate all differences as the poet and her lover believed it did.

“you keep to your language / while I struggle to understand…wanting to see your acceptance / behind the round blue eyes.” Based on this description, we can infer that her lover is white with blue eyes. Sanchez struggles with the language barrier and her Mexican heritage in an assimilationist environment: “am I being too Spanish / or not enough English?” Then, Sanchez ends the poem with a hint of suspicion towards her lover and expresses her vulnerability as being perceived as not American enough. Love does not seem to mitigate all differences as the poet and her lover believed it did.

Sources:

Anzaldúa Gloria. Borderlands : The New Mestiza = La Frontera. Fourth edition, 25th anniversary ed., Aunt Lute Books, 2012.

Cockrell, Cathy. “A Labor of Love, a Publishing Marathon.” Berkeleyan, 12 May 1999, https://www.berkeley.edu/news/berkeleyan/1999/0512/alarcon.html. Accessed 27 November 2018.

Lopez, Natashia. “Trying to be Dyke and Chicana.” Chicana Lesbians : The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About. Edited by Carla Trujillo, Third Woman Press, 1991.

Montoya’s Gina. “Baby Dykes.” Chicana Lesbians : The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About. Edited by Carla Trujillo, Third Woman Press, 1991.

Sánchez, Juanita M. “Voz en una carcel.” Chicana Lesbians : The Girls Our Mothers Warned Us About. Edited by Carla Trujillo, Third Woman Press, 1991.