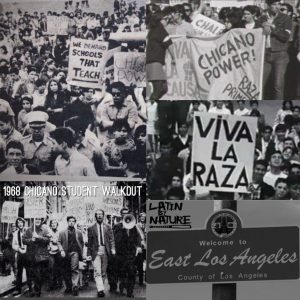

During the late sixties, Mexican- Americans, Chicanos, began mobilizing against the treatment they received in institutional facilities, such as public education and workplaces (“Chicano Movement”). In 1968, there were several high school walkouts in Los Angeles to protest the substandard education these young Chicanos were receiving (Sahagun, “East L.A., 1968“). During the 1969 First National Chicano Youth Conference in Denver, there was a workshop concerning the status of Chicanas within the movement, and it ” ‘was the consensus of the group that the Chicana woman does not want to be liberated’ ” (Vidal 22).This was one of the actions that spurred Chicanas into action. Chicanismo–ethnic pride–was a predominantly masculine ideology. This is apparent in short films, such as “I am Joaquin” and “Yo Soy Chicano” where women were portrayed as abstractions of Mother Earth or symbols of fertility while the men were portrayed as embodiments of revolutionary warriors (Fregoso 12). Chicanas were excluded from the early beginnings of the Chicano and the Second Wave Feminist Movements. It became apparent that Chicanas needed to create a space to air their unique grievances. This space was found in the poetry and other writings produced during the era.

During the late sixties, Mexican- Americans, Chicanos, began mobilizing against the treatment they received in institutional facilities, such as public education and workplaces (“Chicano Movement”). In 1968, there were several high school walkouts in Los Angeles to protest the substandard education these young Chicanos were receiving (Sahagun, “East L.A., 1968“). During the 1969 First National Chicano Youth Conference in Denver, there was a workshop concerning the status of Chicanas within the movement, and it ” ‘was the consensus of the group that the Chicana woman does not want to be liberated’ ” (Vidal 22).This was one of the actions that spurred Chicanas into action. Chicanismo–ethnic pride–was a predominantly masculine ideology. This is apparent in short films, such as “I am Joaquin” and “Yo Soy Chicano” where women were portrayed as abstractions of Mother Earth or symbols of fertility while the men were portrayed as embodiments of revolutionary warriors (Fregoso 12). Chicanas were excluded from the early beginnings of the Chicano and the Second Wave Feminist Movements. It became apparent that Chicanas needed to create a space to air their unique grievances. This space was found in the poetry and other writings produced during the era.

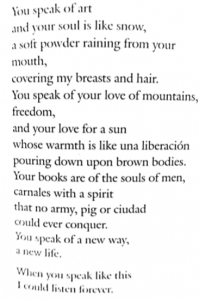

In 1975, Lorna Dee Cervantes wrote “Para un Revolucionario,” highlighting the disconn ect within the Chicano Movement and its actions towards Chicanas. Cervantes at first describes the language and rhetoric of the Chicano Movement in a positive tone. Words such as sun, soft, warmth, and love all have positive connotations. Cervantes is mesmerized by the Chicanos’ proclamation of liberation for la Raza* as she proclaims, “When you speak like this / I could listen forever.”

ect within the Chicano Movement and its actions towards Chicanas. Cervantes at first describes the language and rhetoric of the Chicano Movement in a positive tone. Words such as sun, soft, warmth, and love all have positive connotations. Cervantes is mesmerized by the Chicanos’ proclamation of liberation for la Raza* as she proclaims, “When you speak like this / I could listen forever.”

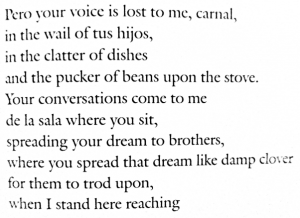

Then, however, the poem takes a drastic shift in tone regarding its subject, El Chicano. Cervantes begins this stanza by stating “Pero your voice is lost to me, carnal.” It was typical of Chicana poets to smoothly transition between English and Spanish as it illustrated the bilingual and bicultural aspect of their identity. The use of carnal is significant because i t signals the recognition of the masculine undertones within the movement. Carnal, blood in Spanish, was frequently used among Chicanos to mean brother/brotherhood. Cervantes then proceeds by listing the attributes of the domestic sphere–cooking, cleaning, child tending– to highlight the Chicana’s position in the household, as well as to indicate her isolation in the movement. The Chicana wants liberation, as well, but she is trapped within the confines of her traditional gender role. She can listen to the Chicanos talk about the revolution in la sala**, but she is prohibited from joining. This portion of the poem highlights the exclusion and sexism present in the Chicano Movement.

t signals the recognition of the masculine undertones within the movement. Carnal, blood in Spanish, was frequently used among Chicanos to mean brother/brotherhood. Cervantes then proceeds by listing the attributes of the domestic sphere–cooking, cleaning, child tending– to highlight the Chicana’s position in the household, as well as to indicate her isolation in the movement. The Chicana wants liberation, as well, but she is trapped within the confines of her traditional gender role. She can listen to the Chicanos talk about the revolution in la sala**, but she is prohibited from joining. This portion of the poem highlights the exclusion and sexism present in the Chicano Movement.

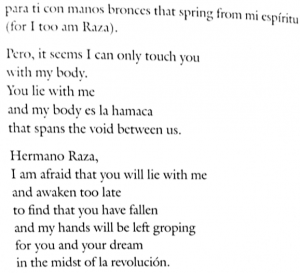

Cervantes re-emphasizes the prevalence of sexism within th e movement in the following excerpt. Cervantes states that she “can only touch [him] with [her] body.” Chicanas were seen as sexual objects, not respectable equals. The last stanza is meant to be read as a warning. The Chicano Movement will fail if it continues to exclude Chicanas from the conversation. It is clear that Cervantes does not want the movement to fail with lines such as “my hands will be left groping / for you and your dream,” but the dream of the revolution will be lost if Chicanas are not adequately represented. How can these men, these Chicanos, proclaim to fight for the liberation of la Raza when they exclude half of it?

e movement in the following excerpt. Cervantes states that she “can only touch [him] with [her] body.” Chicanas were seen as sexual objects, not respectable equals. The last stanza is meant to be read as a warning. The Chicano Movement will fail if it continues to exclude Chicanas from the conversation. It is clear that Cervantes does not want the movement to fail with lines such as “my hands will be left groping / for you and your dream,” but the dream of the revolution will be lost if Chicanas are not adequately represented. How can these men, these Chicanos, proclaim to fight for the liberation of la Raza when they exclude half of it?

*the race

**the living room

Sources:

Cervantes, Lorna D. “Para un Revolucionario.” Infinite Divisions: An Anthology of Chicana Literature. Edited by Tey Diana Rebolledo and Eliana S. Rivero, University of ArizonaPress, 1993.

“Chicano Movement.” Educating Change, 22 June 2005, http://www.brown.edu/Research/Coachella/chicano.html. Accessed 26 November 2018.

Fregoso, Rosa Linda. The Bronze Screen: Chicana and Chicano Film Culture. University of Minnesota Press. 2003.

Sahagun, Louis. “East L.A., 1968: ‘Walkout!’ The day that high school students help ignite the Chicano power movement.” Los Angeles Times, 01 March 2018.

Vidal, Mirta. “New Voice of La Raza: Chicanas Speak Out*.” Chicana Feminist Thought: The Basic Historical Writings. Edited by Alma M. García, Routledge, 1997.

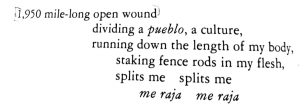

border plays a vital role in illustrating the binary of being Mexican-American. Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands opens with a poem detailing her experience and perception of the Mexico-United States Border. Within the following stanza, the reader can detect the tension within the poem. The “1,950 mile-long open wound” is a reference to the border, and the word choice indicates the pain that is manifested on the border. Anzaldúa clearly states that the border that is meant to divide the United States and Mexico divides her. Anzaldúa describes the border as “una herida abierta* where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before the scab forms it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of the two worlds merging to form a third country–a border culture” (Anzaldúa 3).

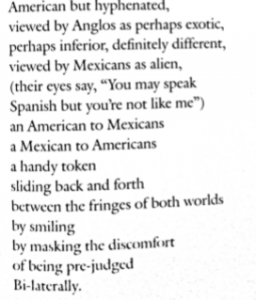

border plays a vital role in illustrating the binary of being Mexican-American. Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands opens with a poem detailing her experience and perception of the Mexico-United States Border. Within the following stanza, the reader can detect the tension within the poem. The “1,950 mile-long open wound” is a reference to the border, and the word choice indicates the pain that is manifested on the border. Anzaldúa clearly states that the border that is meant to divide the United States and Mexico divides her. Anzaldúa describes the border as “una herida abierta* where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds. And before the scab forms it hemorrhages again, the lifeblood of the two worlds merging to form a third country–a border culture” (Anzaldúa 3). e Mexico-United States Border. Mora begins “Bi-lingual, Bi-cultural” establishing the duality of the Chicana, of her lifestyle, and of her language. She hits the central point of tension: “American but hyphenated.” In the eyes of Americans, she is an inferior Mexican. In the eyes of Mexicans, she is an alien American. She does not have a solid space she can claim as her home. She expresses this discomfort as “sliding back and forth / between the fringes of both worlds.” Her life as a Mexican-American will constantly be subjected to “being pre-judged/ Bi-laterally.” This judgement and discomfort is unique to Chicanas, individuals without a home base.

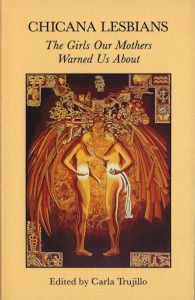

e Mexico-United States Border. Mora begins “Bi-lingual, Bi-cultural” establishing the duality of the Chicana, of her lifestyle, and of her language. She hits the central point of tension: “American but hyphenated.” In the eyes of Americans, she is an inferior Mexican. In the eyes of Mexicans, she is an alien American. She does not have a solid space she can claim as her home. She expresses this discomfort as “sliding back and forth / between the fringes of both worlds.” Her life as a Mexican-American will constantly be subjected to “being pre-judged/ Bi-laterally.” This judgement and discomfort is unique to Chicanas, individuals without a home base. instream Anglo society. Norma Alarcon founded the Third Woman Press in 1979 as a platform for queer and feminists of color to be heard in the Second Wave Feminist Movement. Alarcon states she was inspired to create this publishing company once she realized “there weren’t enough women of color or Latinas… for me to have a conversation with” (Cockrell, “A Labor of Love”). Chicana sexuality was not an issue that was discussed within nor outside the household. Life was dictated largely by traditional gender roles and religion that left little to zero tolerance for any deviations from the norm: “For the lesbian of color, the ultimate rebellion she can make against her native culture is through her sexual behavior. She goes against two moral prohibitions: sexuality and homosexuality” (Anzaldúa 19). The following three excerpts of the poems below by Gina Montoya,

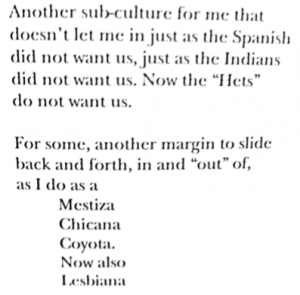

instream Anglo society. Norma Alarcon founded the Third Woman Press in 1979 as a platform for queer and feminists of color to be heard in the Second Wave Feminist Movement. Alarcon states she was inspired to create this publishing company once she realized “there weren’t enough women of color or Latinas… for me to have a conversation with” (Cockrell, “A Labor of Love”). Chicana sexuality was not an issue that was discussed within nor outside the household. Life was dictated largely by traditional gender roles and religion that left little to zero tolerance for any deviations from the norm: “For the lesbian of color, the ultimate rebellion she can make against her native culture is through her sexual behavior. She goes against two moral prohibitions: sexuality and homosexuality” (Anzaldúa 19). The following three excerpts of the poems below by Gina Montoya,  the subsequent marginalization that accompanies it, Montoya is frustrated that she does not have her own place within this community. The stanza following the excerpt on the left begins, “Learning a new language: Lesbian” and continues listing the languages that Montoya has to learn: Lesbian, English, Spanish, and Spanglish. By using words such as learning and language, Montoya implies how foreign this culture surrounding her sexuality is. By listing off the “different languages,” Montoya shows the reader the multitude of her identities. She is not solely lesbian nor Mexican. She is in a constant flux of identities as they play different roles in her life.

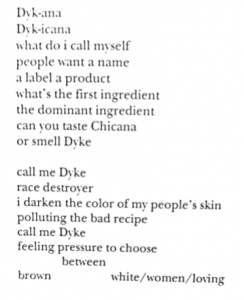

the subsequent marginalization that accompanies it, Montoya is frustrated that she does not have her own place within this community. The stanza following the excerpt on the left begins, “Learning a new language: Lesbian” and continues listing the languages that Montoya has to learn: Lesbian, English, Spanish, and Spanglish. By using words such as learning and language, Montoya implies how foreign this culture surrounding her sexuality is. By listing off the “different languages,” Montoya shows the reader the multitude of her identities. She is not solely lesbian nor Mexican. She is in a constant flux of identities as they play different roles in her life. the reader can see Lopez wrestle with combining these two attributes of her identity. In the end, Lopez coins the term “Chyk-ana” to summarize herself. But this term and unconditional acceptance of self is not easy, Lopez struggles to identify the dominant attribute of her identity: “what do I call myself…what’s the first ingredient / the dominant ingredient.” Lopez also illustrates the widespread homophobia within her community: “race destroyer / I darken the color of my people’s skin.” Shame and anger are implicit within these lines as Chicana Lesbians were degraded even within their own ethnic community.

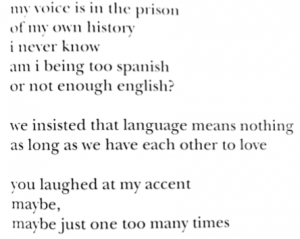

the reader can see Lopez wrestle with combining these two attributes of her identity. In the end, Lopez coins the term “Chyk-ana” to summarize herself. But this term and unconditional acceptance of self is not easy, Lopez struggles to identify the dominant attribute of her identity: “what do I call myself…what’s the first ingredient / the dominant ingredient.” Lopez also illustrates the widespread homophobia within her community: “race destroyer / I darken the color of my people’s skin.” Shame and anger are implicit within these lines as Chicana Lesbians were degraded even within their own ethnic community. “you keep to your language / while I struggle to understand…wanting to see your acceptance / behind the round blue eyes.” Based on this description, we can infer that her lover is white with blue eyes. Sanchez struggles with the language barrier and her Mexican heritage in an assimilationist environment: “am I being too Spanish / or not enough English?” Then, Sanchez ends the poem with a hint of suspicion towards her lover and expresses her vulnerability as being perceived as not American enough. Love does not seem to mitigate all differences as the poet and her lover believed it did.

“you keep to your language / while I struggle to understand…wanting to see your acceptance / behind the round blue eyes.” Based on this description, we can infer that her lover is white with blue eyes. Sanchez struggles with the language barrier and her Mexican heritage in an assimilationist environment: “am I being too Spanish / or not enough English?” Then, Sanchez ends the poem with a hint of suspicion towards her lover and expresses her vulnerability as being perceived as not American enough. Love does not seem to mitigate all differences as the poet and her lover believed it did. nd recognized by several minority women. The editors of Heresies, Third World Women: the politics of being other, discuss in detail the sentiments of the label other. This label created an inferiority complex among these minority women. Katherine Hall’s drawing “The Alien,” published in this 1979 Heresies issue, along with Inés Hernández’s “To Other Women Who Were Ugly Once,” published in Infinite Divisions in 1993, illustrate the dialogue of minority beauty standards.

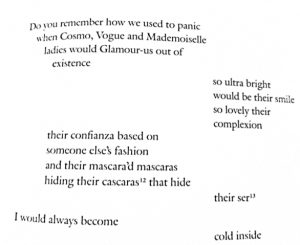

nd recognized by several minority women. The editors of Heresies, Third World Women: the politics of being other, discuss in detail the sentiments of the label other. This label created an inferiority complex among these minority women. Katherine Hall’s drawing “The Alien,” published in this 1979 Heresies issue, along with Inés Hernández’s “To Other Women Who Were Ugly Once,” published in Infinite Divisions in 1993, illustrate the dialogue of minority beauty standards. tandards that hide the authentic person behind the make-up? Hernández states, “Que mataonda,” what a drag to need to constantly fit into a model that is not yourself. The poet claims “resistance to this type of existence.” This is not a way to live. The ending of the poem calls for the embrace of the “natural luz,” the natural appearance, as opposed to the artificial one presented in magazines. .There is an acceptance of one’s appearance despite its contrast to mainstream ideals; this is commonly expressed as “Brown is Beautiful” and is not exclusive to Chicanas.

tandards that hide the authentic person behind the make-up? Hernández states, “Que mataonda,” what a drag to need to constantly fit into a model that is not yourself. The poet claims “resistance to this type of existence.” This is not a way to live. The ending of the poem calls for the embrace of the “natural luz,” the natural appearance, as opposed to the artificial one presented in magazines. .There is an acceptance of one’s appearance despite its contrast to mainstream ideals; this is commonly expressed as “Brown is Beautiful” and is not exclusive to Chicanas.  Growing up in Corpus Christi, Texas, Selena became involved in music through the guidance of her father (Corpus). Her first debut was in the early 1980s as a member of “Selena y Los Dinos” (Corpus). As she garnered fame, Selena became known as the Queen of Tejano Music (Corpus). While her life was tragically cut short at age twenty-three in March of 1995, her influence still lingers. Despite the gap of years from Selena’s rise to fame and my own adolescence, Selena’s story is very personal to me. Representation is essential. Growing up, Selena solidified the message of “Brown is Beautiful” for me. I did not feel the need to struggle to conform to look like the women found on the cover of Cosmo or Vogue magazines. Not only did Selena provide me with the confidence to be proud of how I looked, she also helped bridge the gap between my “American” self and my “Mexican” self–a binary that has been frequently discussed within poetry by early Chicana Feminists. As a child, I tried to assimilate into “American” culture and shed my Mexican heritage. By listening to Selena, I was able to practice my Spanish and reconnect with an identity that I had lost. As Chicanas continue to seek representation in all platforms moving forward, their mere presence in these spaces will inspire young girls like myself to strive for futures that seemed previously unattainable for a Chicana.

Growing up in Corpus Christi, Texas, Selena became involved in music through the guidance of her father (Corpus). Her first debut was in the early 1980s as a member of “Selena y Los Dinos” (Corpus). As she garnered fame, Selena became known as the Queen of Tejano Music (Corpus). While her life was tragically cut short at age twenty-three in March of 1995, her influence still lingers. Despite the gap of years from Selena’s rise to fame and my own adolescence, Selena’s story is very personal to me. Representation is essential. Growing up, Selena solidified the message of “Brown is Beautiful” for me. I did not feel the need to struggle to conform to look like the women found on the cover of Cosmo or Vogue magazines. Not only did Selena provide me with the confidence to be proud of how I looked, she also helped bridge the gap between my “American” self and my “Mexican” self–a binary that has been frequently discussed within poetry by early Chicana Feminists. As a child, I tried to assimilate into “American” culture and shed my Mexican heritage. By listening to Selena, I was able to practice my Spanish and reconnect with an identity that I had lost. As Chicanas continue to seek representation in all platforms moving forward, their mere presence in these spaces will inspire young girls like myself to strive for futures that seemed previously unattainable for a Chicana.