Women truly come in all different shapes and sizes, and consequently feminism should as well. This is why when mainstream feminism failed to include women of all sizes, there were women who came to fill in the gap through activism with groups like the Fat Underground.

The Fat Underground was an organization that acted as a catalyst in the creation and mobilization of the Fat Liberation movement. Based in LA in the 1970s, the Fat Underground did not fight to change discriminatory laws but rather discriminatory thoughts and practices in different aspects of society. These discriminatory practices included those of doctors and other health professionals who perpetuated the unhealthy habits encouraged by diet culture. This approach to reform the health profession stems from the Fat Underground’s roots in the Radical Therapy movement, which sought to reform the mental health profession. According to the rhetoric of the Radical Therapy movement, people with mental illness were not to host the burden of changing themselves. We are instead supposed to change the stigma surrounding mental health. This “change society, not ourselves” ideology was the foundation for much of the activism in the Fat Liberation movement.

The Fat Underground was an organization that acted as a catalyst in the creation and mobilization of the Fat Liberation movement. Based in LA in the 1970s, the Fat Underground did not fight to change discriminatory laws but rather discriminatory thoughts and practices in different aspects of society. These discriminatory practices included those of doctors and other health professionals who perpetuated the unhealthy habits encouraged by diet culture. This approach to reform the health profession stems from the Fat Underground’s roots in the Radical Therapy movement, which sought to reform the mental health profession. According to the rhetoric of the Radical Therapy movement, people with mental illness were not to host the burden of changing themselves. We are instead supposed to change the stigma surrounding mental health. This “change society, not ourselves” ideology was the foundation for much of the activism in the Fat Liberation movement.

With the idea to reform society and not themselves, the Fat Underground utlized this rhetoric: “Doctors are the enemy. Weight loss is genocide” (Fishman). While colleagues and counterparts in academia and others in the early fat rights movement found this rhetoric harsh and urged the Fat Underground to be less  aggressive, they ultimately came to adopt much of the Fat Underground’s logic in their respective fields.

aggressive, they ultimately came to adopt much of the Fat Underground’s logic in their respective fields.

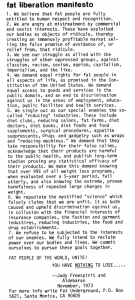

In November 1973, Judy Freespirit and Aldebran published the “Fat Liberation Manifesto” on behalf of the Fat Underground. A manifesto is a written statement declaring publicly the intentions and views of who issued it. In this case, the manifesto outlines the ambitions and views of the Fat Underground, who takes the liberty of speaking on behalf of all fat people. Judy Freespirit and Aldebaran, pioneering members of the Fat Underground, designed these seven points to solidify the desires of the Fat Liberation movement and ended with a call to action. The manifesto first establishes that fat people are entitled to what they were denied on a daily basis: “human respect and recognition.” The other objectives then outline the commercial exploitation of fat bodies by both corporations and scientific institutions. This manifesto marked a key point in the Fat Liberation movement because it is one of the first times there was a public call for unification of fat women and fat people under one common purpose. The rhetoric dictated in this manifesto set the tone for the movement.

Sources: Bracha Fishman, Sarah Golda, “Life in the Fat Underground.” Radiance Magazine Online, http://www.radiancemagazine.com/issues/1998/winter_98/fat_underground.html

Freespirit, Judy, and Aldebaran. “Fat Liberation Manifesto.” Off Our Backs, vol. 9, no. 4, 1979, pp. 18–18. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25773035.

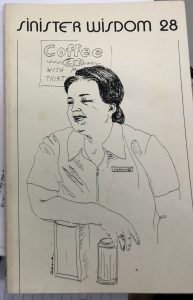

Issue 54: “Lesbians and Religion” Some issues featured works by activists in the fat liberation movement, such as Elana Dykewomon who later was the editor from 1987-1994. Issue 28, pictured here, has a special focus on fatness and body image as well women in the workplace.

Issue 54: “Lesbians and Religion” Some issues featured works by activists in the fat liberation movement, such as Elana Dykewomon who later was the editor from 1987-1994. Issue 28, pictured here, has a special focus on fatness and body image as well women in the workplace.

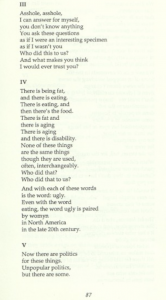

Section III is seemingly a response to the questions asked in section II. In a switch of perspectives, the narrator begins by calling the “friends,” who asked the questions earlier, assholes. The narrator clearly picks up on the mal-intent of the inquiries and indicates that the questions asked of her be posed “as if [she] were an interesting specimen” rather than another human being (line 79). This illuminates how society was dehumanizing fat women.

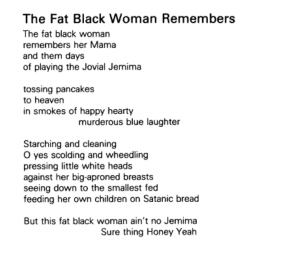

Section III is seemingly a response to the questions asked in section II. In a switch of perspectives, the narrator begins by calling the “friends,” who asked the questions earlier, assholes. The narrator clearly picks up on the mal-intent of the inquiries and indicates that the questions asked of her be posed “as if [she] were an interesting specimen” rather than another human being (line 79). This illuminates how society was dehumanizing fat women.  While the majority of the members of the Fat Underground were white and most of the information found on the Fat Liberation movement is centered on white women, this does not mean the movement was exclusive. Fat women of color also struggled to find their voice in mainstream second wave feminism. They too used poetry as liberation.

While the majority of the members of the Fat Underground were white and most of the information found on the Fat Liberation movement is centered on white women, this does not mean the movement was exclusive. Fat women of color also struggled to find their voice in mainstream second wave feminism. They too used poetry as liberation.