Picture: two enemy groups, battling for prestige and engaged in a spiteful war until a scandalous love blossoms between a young male and female from the opposing sides, eventually resolving the group’s conflicts. Now, name that plot– a tricky task, as there are dozens of modern titles that present this familiar love-versus-war dilemma. It’s a commonly used theme and plot line in cultural products, with Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet widely credited as the origin. Much of modern culture is simply repackaged; art that proves successful is twisted, modernized, copied, and fed to the consumer again. Materials are repeatedly disguised under new movie titles, new star characters, or new settings. Cultural critics argue that economic success in production is valued over the public’s desires and imaginations; the culture industry and producers are entirely absorbed in what will make money, even when this results in products that are entirely lacking in variety and creativity (Adorno). Superficially, these arguments present our culture in an entirely negative and somewhat hopeless light, but this is simply not the case– there is still hope for our culture, however much it may recycle concepts. It is important not to confuse a lack of originality with a lack of worth; our culture still has value despite its repetitive qualities.

Romeo and Juliet is a tale of jinxed love. Both man and wife commit suicide shortly after marriage due to an unfortunate miscommunication in Shakespeare’s famous tragedy in the midst of a raging family feud between the Capulets and Montagues. The familial conflict twists and thickens when Montague son Romeo and Capulet heartthrob Juliet lock eyes and fall in love. However, miscommunications lead Romeo to believe that his beloved Juliet is dead, so he poisons himself. Juliet follows suit, as when she sees Romeo dead, she stabs herself, and the lovers die unlucky deaths. The tragedy is heart-wrenching, and it is painful as the deaths unfold, especially because they are caused by fickle family feuds. The families do eventually throw aside their differences in honor of their losses once they realize their foolishness, however.

(Come, Death, and Welcome!)

While it is maddening to watch both Romeo and Juliet die mistakenly, the deaths strike a chord in the heart of the consumer and make us resent the family feud. Thus the tale pushes for love, and emphasizes the pointlessness of fighting, a meaning that culminates in the deaths of two innocent lovebirds. This valuable moral leads us to why recycling culture is an accepted practice. Relevant to this day as violence is so precedent in the world, the lessons of Romeo and Juliet are applicable anywhere. Furthermore, because the morals behind the story are so applicable, the tale can be versatile– and successful– in the same ways. As long as we continue learning from Romeo and Juliet and other classics, producers will continue to churn them out in new and surprising ways.

Theatre World Award-winning Broadway show West Side Story, for example, features a battle between the Puerto Rican “Shark” gang and the all-white “Jet” gang based on New York City’s West Side that is eventually mediated by a beautiful relationship between Jet Tony and Shark Maria.

West Side Story‘s Tony and Maria embrace despite their different backgrounds (Tony and Maria)

Another popular Broadway show, Grease, which showed for eight years– quite a run for Broadway– delivered a similar message as summer lovers Danny and Sandy end up at the same high school, where their romance is tested by clique lines. However, in a heartwarming musical finale to the catchy tune of “We Go Together”, the lovers are reunited despite their clique boundaries. Love trumps all, especially when accompanied by a Broadway dance riff.

Everyone’s happy after love wins out over clique boundaries in Grease (Grease Live Animated GIF)

Romeo and Juliet’s storyline has also entered into the modern movie industry. Warm Bodies is a 2013 film based on the 2010 novel that takes “love versus war” to the vampire level, as vampire R falls for human Julie– interesting name selections by author Isaac Marion. Their relationship catalyzes a human versus vampire fight and is the beginning of a peaceful coexistence. Another modernized Romeo and Juliet tale, Romeo Must Die presents a kung-fu war between the Asian and black gangs. The film ends peacefully when– guess what– Asian macho man Han falls for African-American Trish.

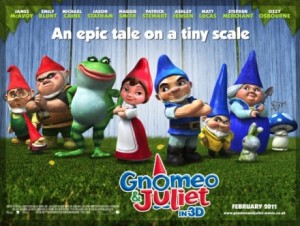

Even modern cartoons are getting in on the action. Gnomeo and Juliet is a garden gnome spinoff in which red-hat gnomes fight blue-hat gnomes, until one fantastically moon-lit night when red-hat Juliet meets blue-hat Gnomeo. They, of course, fall in love, eventually bringing peace and love to the garden. Lion King 2 also features an animated Romeo and Juliet-like tale. Lion leader Simba’s daughter Kiara falls in love with Kovu, a banished lion. Kovu and Kiara’s beautiful relationship eventually sparks peace amongst the clans, and all of the lions live happily ever after.

Lion King 2 teaches a peaceful lesson: “What differences do you see?” (What Differences do you See?)

Everyone loves this kind of story; even cartoon lions and gnomes are now getting in on the romantic Romeo and Juliet love-trumps-violence lesson. There are hundreds of spinoffs in various forms and genres out there in today’s culture– even Shakespeare’s version was based on an older poem. Producers simply can’t help themselves from recycling what’s proven successful, and they’ll feed consumers classics like Romeo and Juliet forever if it works (Adorno). The industries are looking for money, and they fire out movies and books at a relentless pace. Not only is it easier to reproduce an idea than to make something original, but it is also economically safer to build upon a basic tale that has already earned its place in the hearts of the masses. Success is practically guaranteed, furthermore, when a product’s base is a tale as beloved as Romeo and Juliet. However, this trend is not only applicable to this particular Shakespeare piece, as story reproduction in general has been greatly successful and has brought about countless renditions of all types of products. Essentially, a huge portion of modern cultural products are simply reproductions of older literature and ideas (Adorno). Our culture is indeed quite repetitive.

Consequently, modern culture gets a bad rap because of the nature of these retellings. Gnomeo and Juliet, for example, is the recipient of many bad reviews not only because it is a retelling of a story that everyone knows already, but also because it appears to trivialize the lessons presented by the great Shakespeare in his timeless classic Romeo and Juliet. This is the case with many modern retellings. Furthermore, sometimes the lessons presented by modern cultural pieces are considered lessers to those of old literature (Leavis)– a view that is rather unfounded, because if our culture is truly an endless recycling circle, then these “bad” lessons presented in modern culture have origins in these idealized “classics”. It is for these reasons that culture, foolishly, will not accept many modern pieces as its own. These accusations of lack of originality and worth that are cast upon modern cultural products, however, are not deserved.

“An epic tale on a tiny scale”– Gnomeo and Juliet in a nutshell! (An Epic Tale on a Tiny Scale)

The repetitive nature of modern culture does indeed entail the reflection of many of the same lessons, but that does not take away their value. The values behind Romeo and Juliet— that love is more powerful than war– provide an extremely important life lesson. Modern times are pockmarked by the countless acts of terror we’ve experienced recently, from school shootings to marathon bombings, rapes, ISIS, cop violence, and everything in between. Consequently, we all could use a pleasant story of love to remind us that violence is bad and love and peace can prevail. It’s a lesson we forget sometimes, and one that the world desperately needs to remember. Humans tend to forget the lessons they have been taught, so there is no harm in a quick review. Although superficially, the sameness of culture is depressing and makes product consumption feel pointless, there is still value in ideas that may have been repeated.

Additionally, while Shakespeare might have been horrified if he knew that his classic Romeo and Juliet tale was being remade with the help of gnomes and lions, it speaks to the power of the tale that such products are out there. Clearly, people appreciate the lesson enough for it to have been so timelessly popular, and now it can be even more transcendental. Anyone can learn from Romeo and Juliet’s love nowadays, regardless of originality. The versatile methods of lesson delivery can also simply reach a large audience– young children can begin to learn the value of love and peace amidst violence if they watch Gnomeo and Juliet, whereas a Shakespeare reader must be educated and much older to see through the tragedy’s complex wording and fully appreciate the meaning. Those of all walks of life can now appreciate the lesson of Romeo and Juliet because of the volume of its renditions.

(Romance in Gnomeo and Juliet)

Furthermore, it is easier for a consumer to relate to a product when it connects to their own life, so having many different styles of presentations drastically increases the reach of the lessons. Romeo Must Die, for example, will likely hit home with an African-American whose life has been touched by racial violence more so than Shakespeare’s version. Grease works in the same way, as a popularity-driven teenager might be able to see past class lines and exclusion to the value of love more so than he or she would be able to by reading a dense book. Additionally, we must address the idea that people forget things they are taught. Most high schoolers read Romeo and Juliet, and are led to the meaning behind it, but they will likely forget what they have learned about love and life until they watch the West Side Story play years later. The heart can still be warmed by a concept it has already experienced; the lessons will simply be refreshed and deepened upon each new experience. Therefore, there is true value in the variety of presentations of classic tales that consumers have access to in modern culture.

This variety is due to the endless recycling of material that has proven successful in the modern cultural industry. Producers identify the popular stuff– Romeo and Juliet, for example– and twist it in countless ways (West Side Story, Warm Bodies, Lion King 2, and many others) to continue to benefit economically, which leads to an apparent degradation of culture. Culture is shamed for its repetitive nature, but not deservingly. Although cultural products are increasingly similar, there is no harm in variations of the same idea– Gnomeo and Juliet gets the point across just as successfully as Shakespeare did. The basic stories are successful because they are valuable; they possess lessons and morals that everyone needs to learn and experience, like the importance of love and peace despite adversity. The recycled quality of Romeo and Juliet— and most other works of modern culture– brings significant variety to how consumers can experience the work and, therefore, increases the understanding and benefit derived from the lessons presented, as well as the audience to which these lessons are available and relatable to.

Works Cited

An Epic Tale on a Tiny Scale. Digital image. Gnomeo and Juliet Image Quotes. HippoQuotes, 2015. Web. 15 Oct. 2016.

Come, Death, and Welcome! Digital image. Movie Quotes. IMovie Quotes, 2015. Web. 15 Oct. 2016.

Grease Live Animated GIF. Digital image. Grease Live. Giphy, n.d. Web. 15 Oct. 2016.

Horkheimer, Max, and Theodor W. Adorno. “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception.” Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments. Ed. Gunzelin Schmid Noerr. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 2002. 94-136. Print.

Leavis, F.R. “Literature and Society.” The Common Pursuit. New York: George W. Stewart, 1952. 182-94. Print.

Romance in Gnomeo and Juliet. Digital image. Gnomeo and Juliet Image Quotes. HippoQuotes, 2015. Web. 15 Oct. 2016.

Tony and Maria. Digital image. Fanpop. Townsquare Entertainment News, 2016. Web. 15 Oct. 2016.

What Differences do you See? Digital image. Top Tumblr Posts. Rebloggy, Aug. 2014. Web. 15 Oct. 2016.