THREE SHORT ESSAYS ON Žižek

•2. Žižek’s Method

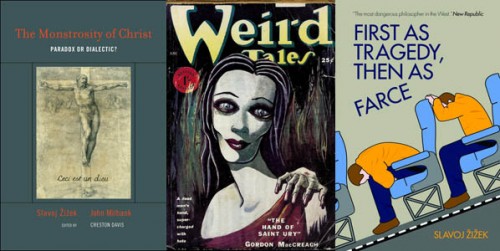

Žižek is above all a Gothic writer, and the admirers who approach him as though he were Louis CK or Reggie Watts are thus falling into a kind of category error. They’ve got the genre wrong, like the people who go to slasher movies and chortle every time the knife comes out. A Gothic writer: It’s not just that Žižek publishes on the kind of accelerated schedule that we more typically associate with pulp fiction or even comic books, though some still unfriendly readers could probably reconcile themselves to his industrial tempo if they began thinking of The Monstrosity of Christ and First as Tragedy not as free-standing volumes, nor even properly as books, but simply as the latest issues in a long-running title—a single year’s worth of Slavoj Žižek’s Adventures into Weird Worlds. The first-order evidence for Žižek’s Gothicism—the cues and triggers that invite us to read his writing as a kind of Gruselphilosophie—are not hard to find: the frequent encomia to Stephen King, to whom even his beloved Hitchcock is finally assimilated; a tendency to explicate Lacan by summarizing the plots of scary movies; a persistent concern with trauma, cataclysm, and grief. Psychoanalysis’s most fundamental insight, he writes, is that “at any moment, the most common everyday conversation, the most ordinary event can take a dangerous turn, damage can be caused that cannot be undone.” So, yes, Žižek is a magnetic and slobber-voiced goof; he is also the theorist of your life where it is going to be worst, the implacable prognosticator of your distress.

But even once we’ve spotted the jack-o-lantern that Žižek never takes off his porch, it is going to be hard to know what to do with it or how to reckon its consequences. What, after all, does it mean to say that a given philosopher is a kind of horror writer? You might be wondering, for instance, if there is a philosophical argument attached to all of Žižek’s horror-talk. It would be possible at this point to survey the philosophy canon and compile a list of concepts or excerptable positions establishing European thought’s many different accounts of terror, trepidation, and unease. Indeed, for the philosophy graduate student, the language’s fine discriminations between panic’s various grades and modes come as it were with the names of Great Thinkers already attached: Hobbesean fear, Kierkegaardian dread, Freudian Unheimlichkeit, the angst, anxiety, or anguish of your preferred existentialist. And there is nothing stopping you from reading Žižek in this manner and so walking away with yet another philosopheme, in which case you might decide that Žižek is a fairly conventional theorist of the spooky-sublime, like so: All language involves a doubling; whenever we name something, we fashion a doppelganger for it. I open my mouth, and where before there was one thing, the object, there are now two, the object and its name, and if I’m thinking clearly I need to be able to distinguish rigorously between the word “table” and the touchable, breakable, enduring-decaying, eighteenth-century Connecticut batten door upon which I am now typing. Žižek takes the position that language thus severed from its referents is always on the side of fiction, fantasy, and ideology. You can only be sure that you are in the presence of something real if this kind of doubling hasn’t taken place, if, in other words, the object hasn’t been surrounded by verbal shadows of itself. If you can talk about something, then it is by definition untrue; it has already been translated into a kind of derealized chatter. And if it’s true, or if it’s Real—because that’s the philosopheme you are about to pocket: the Real—then you can’t talk about it or can’t talk about it lucidly and coherently. But in that case, the only things that get to count as Real are the things that resist being named—those enormities that daunt our congenital glibness—which is to say the worst things: the torsions, the tearings, the ugliest breaks. Nearly everything can get sucked into the order of language, but some few things can’t. What remains is what’s real: the unspeakable.

But perhaps this too-fluid summary is beside the point. For to call Žižek a Gothic writer is finally to say less about the substance of his arguments than about his way of making those arguments—his philosophical style or Darstellung. It is one thing, I mean, to point out that Žižek gives an account of fear, which we could reflect on and debate at the seminar table and then agree with or not. It is another, rather more interesting thing to observe that Žižek is trying to scare you—not just to explain the uncanny to you, but to raise its pimples in your armflesh: “What unites us is that, in contrast to the classic image of proletariat who have ‘nothing to lose but their chains,’ we are in danger of losing everything.” Critical theory, of course, has always been readable as a mode of Gothic writing, just another subgenre of the dark-fantastic, with Freudianism and Foucauldianism assuming their place on the bookshelf alongside vampire novels and chronicles of crewless ghost ships and other such stories of the damned. Marx describes the commodity as “phantom-like” and calls capital a bloodsucker and attributes to it a “werewolf-hot-hunger.” Freud makes of psychoanalysis a sort of ghost story and instructs his followers to conduct therapy as though it were a séance or an exorcism—a making-the-spirits-walk. In German, the other name for the unconscious is not reassuringly distanced and Latinate, but bluntly, forbiddingly vernacular. The Ego, this is to say, does not share our person with the Id—that’s not how Freud puts it. Das Ich is chained to das Es, “the Me” to “the It,” or, if you like, to It. Walter Benjamin, meanwhile, asks us to declare our solidarity with the dead. Adorno requires that you take a shard in the eye. Foucault recasts Left Weberianism as a paranoid thriller, a story about imprisonment and surveillance and the impossibility of outrunning power. Critical theory, this is all to say, needs to be read not only as a teaching or a storehouse of oppositional arguments, but also as a historically inventive crossbreeding of philosophy and genre fiction. The Frankfurt School Reader is, in that sense, one of the twentieth century’s great horror anthologies. If we now insert Žižek into this philosophical-literary timeline, we should feel less awkward naming some of his writing’s schlockier conventions: his direct emotional appeals to the reader; his sudden juxtapositions of opposed argumentative positions, which recall less the patient extrapolations of the dialectic than they do the jump cuts of summer-camp massacre movies; his pervasive intermingling of high and low, which marks Žižek’s arguments as postmodern productions in their own right, against which the genre experiments of Freud or Benjamin will seem, in retrospect, downright Jamesian and understated and belletristic. Das Ding an sich is just about hearable as the name of a B-movie: The Thing In Itself!

But this isn’t yet to say enough. I want you to agree that the Gothic in Žižek is something more than a reasoned-through philosophical position, offered to the reader to adopt as creed or mantra. But it is also something more than a sinister rhetoric or set of literary conventions—more than a palette of gruesome flourishes borrowed from the horror classics. In Žižek’s writing, the Gothic attains the status of a method. This will need to be explained, but it’s worth it: It is a tenet of Lacanianism that things in the world have trouble cohering or maintaining their integrity; this is true of persons, but it is every bit as true of institutions or, indeed, of entire social fields. One of the great Lacanian pastimes is thus to scan a person or a piece of writing or a historical-political scene for evidence of its (her, his) fragmentation or disintegration. To the bit of Sartrean wisdom that says that all identity is performance, the Lacanians add a qualifier: All identity is failed performance, in which case it is our task to stay on the lookout for a person’s protrusions and tells and prostheses, the incongruous features that seemingly put-together persons have not been able to absorb into their specious unity. In what specifiable ways are you least like you claim to be? Where is your Adam’s apple, because it’s probably not on your neck? Now once you get good at asking such questions of people, the challenge will be to figure out how to ask them again of the systems in which people reside. The Real—whatever lies menacingly outside of discourse—can take several different forms: Most obviously, it can name external trauma: assaults upon your person, the bullet in your belly, your harrowing. But it might also name your own disgusting desires, the ones you are least willing to own. Or it might name the totality (of empire, say, or global capitalism). Any concept that we form of the totality is going to be a reification, of course, something theorized, which is to say linguistically devised or even in some sense made up. But the totality-as-such, as distinct from this or that concept of totality, will persist as an unknowable limit to our efforts. It will be, to revise an old phrase, a structure palpable only in its effects, with the key proviso now being that the only effects that matter are the unpleasant ones: a structure palpable only in its humiliations. The world system is the shark in the water. Again, the Real might name a given social order’s fundamental antagonisms—the conflicts that are so basic to a set of institutions that no-one participating in those institutions can stand outside them. Or the Real might name the ungroundedness of those institutions and of our personae, their tenuous anchoring in free choices and changeable practices. So if you want to write political commentary in the style of Žižek, you really only need to do two things: 1) You scan the social scene that interests you in order to identify some absurd element within it, something that by official lights should not be in the room. Political Lacanianism in practice tends to be one big game of “Which one doesn’t belong?” or “One of these things is not like the others.” And 2) You figure out how this incongruity is an index of the Real in any of those varied senses: trauma, the drive, the totality, antagonism, or the void. You describe, in other words, how the Unspeakable is introducing anomalies and distortions into a sphere otherwise governed by speech.

So that’s one version of Žižek’s Gothic method. There are thus three distinct claims we’ll need to be able to tell apart. We can say, first, that Žižek likes to read Gothic fiction and also the eerier reaches of science fiction—and that’s true, though he precisely does not read them the way a literary critic would. It has always been one of the more idiosyncratic features of Žižek’s thought that he is willing to proclaim Pet Sematary a vehicle of genuine analytic insight or to see in horror stories more broadly a spontaneous and vernacular Lacanianism, in much the same way that old-fashioned moral philosophers used to think of Christianity as Kantianism for people without PhDs. To this observation we can easily add a second: that Žižek himself often reads as though he were writing speculative fiction, as in: You are not an upstanding member of society who dreams on occasion that he is a murderer, you are a murderer who dreams every night that he is an upstanding member of society—though keep reading in Žižek and you’ll also find: torture chambers, rape, “strange vibrating noises.” And yet if we’re taking Žižek at his word, then the point is not just to read Gothic novels, nor yet to write them. We must cultivate in ourselves, rather, a determination to read pretty much everything as Gothic. Once we’ve concluded that horror fiction offers a more accurate way of describing the world than do realist novels—that it is the better realism, a literature of the Real—then the only way to defend this insight will be to read the very world as horror show. It will no longer be enough to read Lovecraft and Shirley Jackson. The Gothic hops the border and becomes a hermeneutics rather than a genre. Anything—any poem, painting, person, or polity—will, if snuck up upon from the right angle, disclose to you its bony grimace.

This approach should help us further specify Žižek’s place on the philosophical scene. It is often complained that Hegelian thinkers—Adorno, Wallerstein, Jameson—subdue their interlocutors not by proving their arguments false but precisely by agreeing with them. Going up against a Hegelian, you find yourself less refuted than outflanked—absorbed, reduced, assigned some cramped nook in the dialectical apparatus. That’s a point we can now extend to Žižek, in whose writing the Gothic gets weaponized in precisely this Hegelian way. Horror becomes a device, a move, a way of transforming other people’s arguments. When Žižek engages in polemic with some peer, his usual tack is not to controvert his adversary’s arguments, but rather to improvise an eerie riff upon them, to re-state his opponent’s claims in their most unsettling register. You can call this the dialectic, but you might also call it pestilence. Žižek infects his rivals with Lacan and forces them to speak macabre versions of their core positions: undead Heidegger, undead Badiou, undead Judith Butler.

Three of these fiends we will want to single out:

•Žižek summons zombie Deleuze. It is often remarked that critical theory in the new century has taken a vitalist turn. The trials-by-epistemology that were the day-to-day business of the long post-structuralist generation have given way to the endless policing of ontologies. Graduate students accuse each other of possessing the wrong cosmology or of performing their obeisance to the object with insufficient fervor. Deleuze and Guattarí can be corrected only by those proposing counter-ontologies. Claims get to be right because Bergson made them. You are scared to admit that you wrote your whole first book without having read Spinoza. Nietzsche is still quotable, but only where he is most ebullient and alpine. You ask which description of the stars, if recited consequently to its last rhyme, will reform the banking system and unmelt the ice caps. Klassenkampf seems less interesting than theomachia. What is less often remarked is that vitalism has only returned to the fore by consenting to a major modification—a fundamental change in its program and priorities—only, that is, by agreeing not to grant precedence to those things we used to call “living.” The achievement of the various neo-vitalisms has been to extend the idiom of the old Lebensphilosophie—its egalitarian cosmos of widely shared powers, its emphasis on mutation and metamorphosis—to entire categories of object that vitalists used to think of themselves as opposing: the inanimate, the inorganic, and the dead. It is in this sense misleading to call Deleuze a Spinozist without immediately noting that his Spinoza has been routed through La Mettrie and the various Industrial Revolutions and the Futurists, which makes of schizoanalysis less a vitalism than a profound updating of the same, such that it no longer has to exclude the machine—a techno-vitalism, then, for which engines are the better organisms, and which takes as its unnamed material prompts epochal innovations in the history of capitalism itself: the emergence of the late twentieth century’s animate industrialisms, flexible manufacturing and biotech, production producing and production produced.

So that’s one vitalism of the unliving, but there are others. Jane Bennett claims for her ontology the authority of her great lebensphilosophische forebears—Spinoza, Bergson, Hans Driesch, Bakhtin—and yet calls matter “vibrant” rather than “vital,” because she wants her list of things living and lifelike to include national electricity grids and the litter thrown from the windows of passing cars. Bennett is trying to imagine a United States that has become in a few key respects more like Japan—an America in which Midwesterners, possessed by an “irrational love of matter,” hold funeral services for their broken DVD players and pay priests to bounce adzuki beans from off the hoods of newly purchased trucks. The phrase “vibrant matter” might hearken back to William Blake’s infinite-in-everything, but Bennett uses it mostly to refer to the consumables and disposables of advanced capitalist societies: to enchanted rubbish dumps and copper tubing and other such late-industrial yōkai. The task, again, is to figure out how to be a vitalist on a planet without nature—a pantheist of the anaerobic or Spinoza for the Anthropocene. Bennett herself says that what interests her is above all the “variability” and “creativity” of “inorganic matter.” In that context, the achievement of the adjective “vibrant” is to recall the word “vital” without entailing it: not alive, merely pulsating; not vitalist, but vitalish.

What we can now say about Žižek is that he offers his own, rather different way of dialectically revising the older vitalisms. His point is that most people already happen upon the cosmic life force—in their everyday lives and without special philosophical tutoring—and that such encounters are, on balance, terrifying. The élan vital is not your iPod’s morning workout mix; nor is it some metaphysical energy drink. It is the demiurge that makes of you “a link in the chain you serve against your will”—the formulation is Freud’s—“a mere appendage of your germ-plasm,” not life’s theorist and apostle, but its stooge and discardable instrument. Psychoanalysis is the school that takes as its starting point the repugnance that we properly feel towards life—a vitalism still, but one with all the judgments reversed, a necrovitalism, in which bios takes on the attributes that common sense more typically associates with death, its nullity, above all, and its blind stupidity. One of Žižek’s favorite ways of making this point is by reminding you of how you felt when you first saw Ridley Scott’s Alien—movie of cave-wombs and booby-trapped eggs, of male pregnancies and forced blow jobs, which ends when the undressed woman finally lures from his hidey-hole the giant penis monster, the adult alien with the taut, glossy head of an erection. But we might also think of the matter this way: In the early 1950s, Wilhelm Reich—the magus of western Maine, Paracelsus in a lab coat, the ex-Freudian who thought he could capture the cosmic life force in shoeboxes and telephone booths—organized something he called the Oranur Experiment. Reich had by that point begun styling himself the counter-Einstein, foil and counterweight to the Nobel Laureate of Dead Cities, dedicated to building the nuclear age’s new and sorely needed weapons of life. He had to this end procured a single needle of radium; the idea was that he would introduce this shaving of Nagasaki into a room supercharged with élan vital so that he could observe the cosmic forces of death and the cosmic forces of life fighting it out under laboratory conditions. It did not go as he’d planned. Reich panicked when he discovered, not just that the radium was in some sense stronger, but that the radioactivity had contaminated and rendered malevolent the compound’s orgone. The cosmic life force hadn’t been obliterated; it had been turned, made sinister, recruited over to do the work of death. Žižek, we might say, is the theorist of this toxic vitality; the one who thinks that orgone was bad to begin with; the philosopher of rampant and metastatic life.

•Žižek summons zombie Levinas. It might be more precise to say that Žižek summons the zombie Other or the Neighbor-Wight. Either way, poring over Žižek’s response to Levinas is your best chance at learning how to replicate his achievement—how, that is, to turn philosophers you dislike into your reanimated thralls. Derrida delivers the funeral oration; Žižek returns with a shovel later that night. The spell you will read from the Lacanian grimoire has three parts:

-First, you seek out the moment in your rival’s system where his thinking is already at its creepiest. Chapbook summaries of Levinas often make him sound like a fairly conventional European moral philosopher, as though he hadn’t done anything more than cut a new path, dottering and roundabout, back to the old Kantian positions about the dignity and autonomy of other people. It is easy, I mean, to make Levinas sound inoffensive and dutiful. The wise man’s hand silently cups the chin of a stranger. It will be important to insist, then, that ethics-as-first-philosophy harbors its proper share of sublimity or even of something akin to dread. We know that Levinas’s first step was to adjust Husserl’s doctrine of intentionality: So consciousness is always consciousness of something—sure enough. And all thinking is directed outward; it cannot not refer—granted. But intention, even as it fans away from me in a wide, curving band, will meet obstacles or opacities, and it is by fixing our attention on these stains in the phenomenological field that Levinas develops what he himself calls “a philosophy of the enigma”—a kind of anti-phenomenology in which thinking begins anew by giving priority to what does not appear and in which it falls to me to sustain and shepherd this strangeness I have just discovered in the Not-I. This is a program whose uncanny and un-Kantian qualities we could restore only if we agreed to set aside Levinas’s own undarnably worn-out language—alterity, the Other, otherness—and to put “the Alien” in its stead: an ethics of the Alien would ask us to look upon the face of the Alien so that we can better understand the tasks of being-for-the-Alien. For current purposes, what we’ll want to keep in mind is that Žižek has no beef with this Levinas. He agrees after a fashion with the doctrines of alterity and can easily translate their claims about the obscurity of other people into Lacanian observations about the modes of appearance of the Real. But again, it’s not the argument that matters; it’s the method: Žižek has to find at least one point of agreement with Levinas, because that’s how the zombie hex gains access to its mark.

-So that’s the first step. You make a point of agreeing with your rival by finding that one argument of his that is already pretty occult. The next step, then, is to show how he nonetheless runs away from the creepiness he has conjured. Žižek’s complaint against Levinas is easily summarized. He thinks that the ethics of alterity, far from demanding difficult encounters with other people, encourages me to keep my relationship to others within strict bounds—to delimit, attenuate, and finally dull such encounters. Totality and Infinity is the handbook for stage-managing a counterfeit otherness, as a moment’s reflection on two of the words we most associate with Levinas should suffice to show. Who, after all, are the people who routinely allow themselves to be “caressed”? A Levinasian ethics takes as its paradigmatic others people with cheeks at the ready: lovers and children and hospice patients. The attitude it means to cultivate in us is accordingly amorous or avuncular or perhaps candy-striping. The moral person is the one in a position to dandle and cosset. The language of “the Neighbor,” meanwhile, forfeits even the slight provocations of the word “Other,” making strangers proximate again, returning outlanders to their position of adjacency. Neighbors aren’t the ones who draw out of you your hitherto unsuspected capacities for righteousness. They are the ones-to-whom-you-loan-cordless-drills, the ones-who-could-afford-to-buy-on-your-block. Psychoanalysis, then, is where Žižek would have us look for a philosophical program that does not housebreak the Other in this way, though the phenomenologists, if they are to follow him there, will have to agree to reinstate the entire, outmoded metaphysics of appearance v. essence, since those who go into analysis are consenting to set aside public facades and facile self-perceptions and are learning instead to speak the secret language of hidden things. The more-than-Levinasian task, at any rate, would be to find a way to live alongside that person, the person whose unspoken desires you would doubtless find ugly. Other people would terrify you if you knew them well—that is the most remorseless, Freudian plain speech—and it is in the dying light of that claim that Levinas’s thinking looks suspiciously like an excuse not to know them. A psychoanalytically robust account of Otherness would therefore have to reintroduce you to the people next door, that “inhuman” family with whom you now share a hedge, where by inhuman Žižek means “irrational, radically evil, capricious, revolting, disgusting.” Can you hew to the ethics of neighborliness even when a vampire buys the bungalow across the street? Are you willing to caress not just an unfamiliar face but a moldering one? Methodologically, the point we will not want to miss is that Levinas now stands accused on his own terms of having replaced the Alien with the Other, of having persuaded you to stuff your ears against your neighbors’ shenanigans, of having evinced once again what he himself once called the “horror of the Other which remains Other.” We put up with other people as long as they put up a face. And here, finally, is the portable technique, which you can bring to bear against any theorist and not just against the radical ethicists: When you read a rival philosopher, you will want to take whatever creepy argument he already proposes and find a way to make it a whole lot creepier. That will be your chance to conduct a kind of body swap, to replace the philosopher with a more consequently unpleasant version of himself.

-So that’s the second step. Step three is: You welcome your rival into the army of the dead, making sure that he realizes that he is just one monster among many such. Here’s where the hoodoo gets tricky. A Levinasian ethics presents itself to us as intimate, a thought nestled between two terms, Me and the Other, where the latter means “the neighbor and his mug at strokable distance.” And yet the term “Other” is incapable of this kind of grazing approach; it is barred in its very constitution from ever rubbing noses with us. For the word indicates no particular second person but only the anonymous and shrouded Autrui. If I speak only of “the Other,” with no further specification, I could be referring to anyone but me. The concept produces no further criterion and calls no-one by name. Behind its sham-individuation there thus lurks the mathematical sublimity of the crowd, impersonal and planet-filling. At this point you have two options: You can decide that the ethics of alterity is ineffectual because self-consuming in this fashion, claiming to preserve the irreducible strangeness of the other while in fact washing such peculiarities away in a bath of equal and undifferentiated otherness. The philosophical system’s organizing term is, as ever, what betrays it. Alternately, you can decide that a Levinasian ethics can survive only by generalizing itself, by accepting its own faceless abstraction as a prompt and so by agreeing to become categorical. If we follow this second route, we will have to say without blushing that Levinas’s thought as it has come down to us was already characterized by a pressure, irregularly heeded, to all-but-universalize. The term Other directs my moral concern recklessly in all directions, sponsoring a universalism to which I am the only exception—a humanism minus one.

But then it should be easy to add the subtracted one back in. It should be easy, I mean, to get the Me to takes its place among those many indistinct others and thereby to make Levinas’s universalism complete. It will be enough, in fact, to call to mind the basic dialectical idea that we do not cognize objects singly, but only relationally or in constellations. This means, among many other things, that the Me and the Other strictly imply one another. If my action in the world didn’t reach a certain limit, if I didn’t routinely knock into other objects and persons, if these latter didn’t reliably humble me, then I wouldn’t even have a sense of myself as a Me, which is to say as something that does not, in fact, coincide with the world. But then the Other and the Me are not fixed positions; they are conceptually unstable and even in some sense interchangeable. I can obviously switch places with the other; I am other to the Other, who, in turn, is a Me in her own right. As soon as I concede this, I have discovered my own alien-ness. Second, and as an intensification of these Hegelian reciprocity games, we can collapse the two terms into a single formation: not the Me and the Other, but the Other-Me or the self as foreign element. This can be managed a few different ways. My experience of becoming—of my own changeability—renders me other to myself, reconstructing the ego as watercourse or Heraclitean series. I do not shake the Other’s hand as though I didn’t know what it was like to be a stranger. But we can also travel a more direct psychoanalytic path to the same insight, simply by noting that I am not transparent to myself, not in charge of my own person, that my own desires and motives are basically incomprehensible to me—that, indeed, I am just another dimness or demonic riddle.

And with that, the terms generated by Levinas’s philosophy mutate beyond recognition. This, in case you missed it, is the culminating step in Žižek’s method: If when reading philosopher X, you hold fast to what is most Gothic in X’s thinking—if you generalize its monstrosities and don’t exempt yourself from them, if you promote Unwesen to the position of Wesen—then other core features of X’s system will break and buckle and shift, until it no longer really looks any more like X’s thinking. To stay with Levinas: The ethics of alterity rotates around a single inviolable prohibition—that I not conclude that all egos are more or less the same; that I not propose a theory of subjectivity that would hold equally for all people; that I not stipulate as the precondition of my welcoming another person that he or she be like me. But if the terms “self” and “other” cannot be maintained in their separateness—and they can’t—then this injunction will be lifted, and Žižek can improvise in its stead a paradoxical argument in which alterity becomes the vehicle of our similarity, in which I realize I am like others in their very otherness, in which the Hegelian homecoming comes to pass after all, but on the terrain of alienation and not of the self, in which what establishes our identity is not some human substance, but our inevitable distance from such substance—which distance, we, however, share. There thus arises the possibility that I will identify with the Alien, not in his humanity, but in his very monstrosity, as long as I have come to the conclusion first that the world’s most obviously damaged people only make public the inhumanity that is our common portion and my own clandestine ferment. And out of such acts of identification—and not of pity or tolerance or aid—Žižek would build, in the place of Levinas’s philosophy à deux, a global alien host or legion of the damned. Radicalize what is creepiest in your rival, in other words, and then make it universal. This brings us to Episode Number Three, in media res, as they say: already in progress…

•Žižek summons the zombie multitude. I want to point out two more instances of this horror-movie universalism—two more cases, that is, in which Žižek takes one of radical thought’s settled positions and contagiously expands its orbit. What you’ll want to pay attention to is how each position leads to the same conceptual destination, which is the undead horde—Levinas has just led to the horde; and now Rancière will lead to the horde, and then Agamben will, too, like characters in a Lucio Fulci movie getting picked off at twenty-minute intervals. The horde: We’ll want to consider the possibility now that the cadaver-thronged parking lot is a post-political society’s last remaining image of the unmediated collectivity, the term that, having driven from consciousness the gatherings and aggregates posited by classical political philosophy—the assembly, the demos, the populo, the revolutionary crowd—must now be asked to absorb into itself the indispensable political energies we used to expect from these latter. Can we get the walking dead to mill about the barricades?—that is another of Žižek’s driving questions. Will they know to throw rocks?

One path to the horde begins with Rancière’s idea that politics proper belongs to “the part that has no part”—which is the philosopher’s oxymoronic term for the disenfranchised, those who are important to the system’s functioning but who don’t in the usual sense count, who don’t get to take part and who have no party. Rancière’s claim—and sometimes Žižek’s, too—is that only the agitations of such people (refugees, guest workers, the undocumented) so much as deserve to be called “politics,” because it is only at a system’s roiled margins that basic questions about a polity can be raised, questions, that is, about its scope and constitution. Anything that happens in the ordinary course of government takes the state’s functioning for granted and so isn’t really about the polis—is not, in that sense, “political.” On the face of it, this is a terrible idea. Rancière’s position is anti-constitutional and anti-utopian and indeed committed to failure. My actions only get to count as political provided the state does not recognize me, and as soon as I succeed in convincing someone in power to look me in the eye or indeed to act on my behalf, I cede my claim to be a political actor and become just another pawn of policy makers and the police. There is, in this sense, no such thing as getting the state right; every political breakthrough is actually a setback. To frame your program in terms of “the part that has no part” is to show contempt for those parts-with-parts, absolutely any parts, even though some of these portions will be quite meager. This has made Rancière ill-equipped to talk about what we might call the part that has little part: the native-born working classes, the rural poor, the jobless, the ineffectually enfranchised.

So can Rancière’s thinking be Gothically universalized? It is one of the more attractive features of Žižek’s thinking that he corrects Rancière at just this point and in just this fashion, insisting on the instability of the conceptual pair around which the politics of parts usually turns, inclusion-exclusion, as in: Politics is only ever out there; here there is only administration. That last sentence turns out to be untenable, for even the part that has no-part is not simply excluded. It is one of radical thought’s lazier habits to treat the word “margins” as though it meant the outside when it fact it means the space just inside the door, the page’s extremity and not the empty air that surrounds the lifted book. More: Even the word “exclusion” never refers to simple separation or distance. You have to have had some contact with a system for me to be able to say that you are excluded from it; the very concept depends on some thread or temporary node of connection. The gauchos of the Uruguayan plains may not be represented in the Danish Folketing, but they aren’t excluded from it either. “Exclusion” contains the idea of “inclusion” within itself and is not the latter’s simple opposite. Genuine apartness would require a different concept. This observation will allow Žižek to fold the old proletariat back into the category of the part that has no part. Working people and refugees are actually in similar positions of inclusion/exclusion: the grinding, mutilating condition of being swept up in a system whose inner workings nonetheless seem closed off and impossible to fathom.

One way to think about what Žižek is doing here would be to say that he is trying, within the terms dictated by contemporary European philosophy, to get us to shake off our gauchiste habit, picked up over the social democrat decades, of seeing European workers as basically First World and coddled and deleteriously white. He wants to help us retrieve “a more radical notion of the proletarian”—where more radical means not “more militant,” at least not in the first instance, but merely “more abject.” If I say now that the doctrine of we-all-are-refugees might hold the key to the emergence of a new proletariat, you might object, mildly, that this new proletariat sounds a lot like the old one—the really old one, the one that didn’t yet drive oversized Buicks, the working class stump-armed and black-lunged and blind. There is something new, however, about Žižek’s version of the wretched ones, which is that he’s pretty sure that they include us, the people who actually read his books, the people who know who Žižek is: the second-year university students, the middle-aged art historians, the underemployed web designers, the gap-year backpackers. “Today, we are all potentially homo sacer”—and then that’s a second, unusually clear instance of his Gothic universalism right there, now keyed to Agamben, who, once whammied, will produce an image of the concentration camp victim as Everyman or bare life as Ordinary Joe. To be a new-model proletarian is simply to know that your life, if not yet ghastly, is nonetheless exposed and insecure—wholly vincible. In place of Hardt and Negri’s squatters and street-partiers and Glo-Stick communards, Žižek means to fill the streets with a multitude less than human. It might take a minute for this idea to sink in. The new proletariat will be built out of homines sacri. Žižek’s thrilling and preposterous idea is that having failed to organize fast-food chains or big-box retail, we might yet organize ourselves on the basis of la vita nuda—that the Musselmänner might form a union and yet remain Musselmänner, that those who have lost even the instincts of self-preservation, who have stopped swatting the flies that lay eggs in their open sores, might be made to see the point of collective bargaining.

It has become almost obligatory over the past decade to argue that fear lives on the Right, that terror is a means of social control, that one could defeat Al Qaeda and the Patriot Act at once if only one would resolve to be unafraid, if only we could make ourselves okay with not being safe. It is against the Left machismo of those arguments, so many rehashings of the old Spinozist idea that “fear makes us womanish,” that Žižek’s accomplishment over the last decade can be measured, as he has set about to reclaim terror as one possible platform for emancipation and revolutionary equality, to help us imagine a communism for the screamers and the tearful and the scared. Not that Žižek is offering to make you any less frightened. He will not give you refuge or grab your hand or quietly sing nonsense lyrics into your ear. A politics of militant fear does not begin by offering solace. Quite the contrary: Our task will be to communicate fear and to amplify it. You have a few different options as to how you might go about this. You can issue reasoned admonitions, explain to us soberly about the threats and the thresholds and the no-going-back: two degrees Celsius, go ahead tell us again. Or you can make us feel your own foreboding, as also the grief that is fear’s come-true aftermath: Show us the photographs of Katrina graffiti—“Destroy this memory,” one picture records, in white paint on a flooded brick house, in good, teacherly cursive, no less. But it has been left to Žižek to propose a radically darkened politics, a politics that, no longer content to protest the ongoing catastrophe, has taken the disaster into itself and begun to root for ruin. We are the ones they were supposed to be afraid of. In George Romero’s Land of the Dead, the zombies are for once oddly purposeful, these animate corpses with faces torn into tragic masks, whose first, returning memories are of what it was like once to work and when not working march. You are probably already hurting. A just politics is going to hurt a whole lot worse.

MORE SOON…