By Max Dugan-Knight

Max, Class of 2016, is a Political Economy major from Toronto, ON

On October 19th Canadians were presented with a stark choice on a number of broad political questions. The difference between Stephen Harper’s Conservative Party and each of the parties contesting control of Parliament was vast and generally well understood. Many elections lead to a focus on factors other than policy, like style and personality. This election certainly had its share of personal attacks and competing styles, but the fundamentally opposing policy plans put forward by the leaders offered Canadians two very different options for the path the country should take. Canadians responded definitively by electing the opposing Liberal Party to a majority, and Justin Trudeau to Prime Minister.

Perhaps no issue presented a choice as stark as how to respond to climate change. Stephen Harper has consistently downplayed its importance and instead emphasized the need for unrestrained economic growth. (Smith 2008, Paehlke 2008) Canada became the only country to withdraw from the Kyoto protocol with his government at the helm, an accord that he criticized by saying that “It focuses on carbon dioxide, which is essential to life, rather than upon pollutants.” (Paehlke 2008, 88) That Harper did not consider carbon dioxide a “pollutant,” reflects his attitude to climate change. All opposing parties called for much greater action on climate change. Despite differences between the opposing parties’ climate platforms, it was clear that voting for Harper’s Conservatives was voting for continued inaction while voting for any of the opposing parties was supporting more ambitious climate policy. Simply put, single-issue voters that cared strongly about climate change would not have voted for Stephen Harper; those strongly opposed to climate action would have supported Harper over any other party. Harper clearly laid out his climate plan in Canada’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) submitted prior to the negotiations in Paris, and it has been criticized both internationally and by opposing Party leaders for its sluggish commitments. Who to vote for other than the Conservatives was a more difficult question facing voters looking for change that was complicated by considerations like strategic voting, but the point is that on climate change there was little ambiguity: the major divide was between Harper’s conservatives and the opposing parties.

Was it an important issue?

How important, then was climate change in determining who Canadians voted for in this election? One way to attack this question is to look at how prominently the issue featured in the lead up to the election in things like the leaders debates. There were five major leaders debates during the campaign. Some focused on specific topics like the economy or foreign policy and some were more general but all except one, featured discussion on climate change. The first debate included Elizabeth May, the leader of the Green Party who proved very effective at bringing up issues like the Keystone XL and Energy East pipelines. Though opposition leaders Mulcair and Trudeau were very careful not to make any commitments in this discussion, none held off their attack of the incumbent. The second debate focused on the economy and was the only one not to feature a discussion of climate change. In the third debate, held in French, the dynamic was similar with Bloc Québécois leader Gilles Duceppe, joining in the harsh criticism of Harper’s inaction. The fourth debate featured an important discussion on international commitments and Harper’s perceived failure in regards to Kyoto. In this debate, Trudeau outlined his intention to leave the power in the hands of the provinces. In the final debate, the discussion of “Canada’s place in the world” focused largely on climate change and failures like Kyoto.

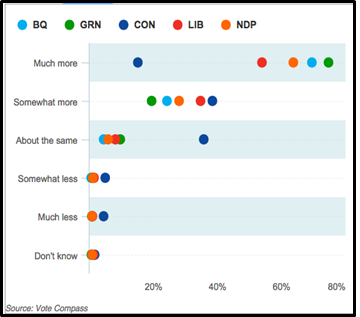

Throughout these debates there was important criticism of proposals and historical policies between the NDP and Liberal parties but the overwhelming feeling was one of Canada having lost its international reputation as result of the lethargy of Harper’s Conservatives. Climate change was by no means the most important issue in this election and I cannot think of an election anywhere, at any time, that it has been; so one useful way to analyze its importance is to compare it to other elections. For instance, in the American federal election in 2012 neither Barack Obama, nor Mitt Romney explicitly mentioned the warming of the planet until Hurricane Sandy struck just weeks before election day. (Merica Oct 30, 2012) This is in sharp contrast to the repeated, thorough discussion of climate change throughout the Canadian leaders debates. The graph below shows Canadians answers when asked how much should be done to reduce Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions. Canadians supporting each party responded very differently, but the greatest difference is unquestionably between the Conservatives and every other party.

Climate change was discussed repeatedly and Canadians’ opinion on the subject was closely linked to their party allegiance. Certainly, it was not the most important issue in the election, but it was an integral part of a broader rejection of Harper’s policies.

Climate change was discussed repeatedly and Canadians’ opinion on the subject was closely linked to their party allegiance. Certainly, it was not the most important issue in the election, but it was an integral part of a broader rejection of Harper’s policies.

Voting for Change

If climate change was an important factor in the election, the next question is what did Canadians actually vote for. They did not vote for the explicit fixed targets of the NDP. Unlike the NDP and the Green Party, the Liberals published no emissions target in their platform. Trudeau argued instead, that the provinces have already made progress without federal targets and that the next government should support and encourage the provinces in those endeavors. British Columbia has instituted a carbon tax; Ontario is set to join Quebec in a cap-and-trade system as well as having recently phased out all of its coal power plants. More information on all that the provinces are doing independently can be found here. (Stastna Apr 15, 2015) Whether they knew it or not, Canadians voted for provincial autonomy.

Again, the most important thing they voted for was not Stephen Harper. Groups across the country participated in the “Anything But Conservative” movement, informing voters who they should vote for to ensure a Conservative was not elected. (McGregor Aug 31, 2015) They voted for action over inaction and for a greater commitment to participate in international arenas like the approaching COP21. Many critics have described this election as a referendum on Harper. The Canadian parliamentary system lends itself to strategic voting meaning that if a voter decided that she wanted to remove Harper from power, she may choose to vote for the party that poses the best challenge to him instead of the one that best reflects her own preference for policy. Once the Liberal Party began to overtake the NDP in the polls, many Canadians may have made this calculation, which is one way to explain the shockingly strong support for Trudeau’s Liberals. It is difficult to definitively conclude that Canadians prefer Trudeau’s province-led climate action plan over Mulcair’s federally established target, but it is not hard to surmise that when it came to climate change, Canadians rejected Harper’s inaction.

Paris and Beyond

The next question – perhaps the most difficult to answer – is what Canadians will get. The COP21 begins in just a few days. Neither the delegates that negotiate Canada’s commitments, nor the already submitted INDC will have changed going into the conference. How then, will the dramatic electoral shift that we have seen manifest itself in this historic international agreement? First of all, the effect of Justin Trudeau not being Stephen Harper should not be underemphasized. Harper has become remarkably unpopular at international conferences and Trudeau’s presence rather than Harper’s is likely, in and of itself, to create goodwill among other countries’ delegates. Trudeau has also invited opposing party leaders as well as the premiers of the provinces and territories to the conference, and all those who are not facing an election (Newfoundland) have agreed to accompany him. Because of his heavy reliance on provincial initiative, one good signal of what Trudeau’s climate policies will look like is the current leadership in the provinces. The two most populous provinces, Ontario and Quebec have premiers from the Liberal party who have called for climate cooperation. Even Alberta, the stronghold of the Conservative Party and home to the oil sands, has new leadership in Rachel Notley who just days ago announced an economy-wide carbon tax and a cap on emissions from the oil sands. (Giovannetti Nov 22, 2015)

All this is to say that I am hopeful that the provincial autonomy approach will prove fruitful. I would be very skeptical of a similar Trudeau claim if he lacked the support from the premiers that he seems to have today. More cynically, this conference provides Trudeau with a valuable political opportunity to demonstrate his ability to create immediate change. Because of both the support that Trudeau has in the provinces, and my belief that Trudeau will be politically opportunistic in this respect, I predict decisive climate action in Canadian policy following the Paris conference.

The Canadian election took place less than two months before COP 21 in Paris, presenting a fascinating opportunity to examine the interaction between domestic politics and international agreements. Will the decisive electoral response to the choice presented to Canadians significantly influence the result in Paris? Even aside from concerns about climate change, this question gets at the effectiveness of democratic government the world over. I will be watching closely and analyzing the results in order to answer that very question.

Bibliography

- “CANADA’S INDC SUBMISSION TO THE UNFCCC.” int. 15 May 2015. Web. 1 Oct. 2015. <http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published Documents/Canada/1/INDC – Canada – English.pdf>.

- CBC News. “Vote Compass: Most Feel Government Should Do More to Combat Climate Change.” CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, 17 Oct. 2015. Web. 30 Oct. 2015.

- “Climate Change Action.” Liberal. 1 Sept. 2015. Web. 10 Oct. 2015. <https://www.liberal.ca/policy-resolutions/6-climate-change-action/>.

- Giovannetti, Justin, and Jeffrey Jones. “Alberta Carbon Plan a Major Pivot in Environmental Policy.” The Globe and Mail. November 22, 2015. Accessed November 22, 2015.

- “Le Débat Des Chefs.” YouTube. YouTube. Web. 30 Oct. 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qknqd5mbNgU

- “Munk Debate: Party Leaders Debate Climate Change.” YouTube. YouTube. Web. 30 Oct. 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tn5KA09Jbts

- Merica, Dan. “Sandy Reminds Us of Climate Change and Other Forgotten Campaign Issues – CNNPolitics.com.” CNN. October 30, 2012. Accessed November 25, 2015. http://www.cnn.com/2012/10/30/politics/forgotten-campaign-issues/index.html.

- Paehlke, Robert C. Some like it cold: the politics of climate change in Canada. Between the Lines, 2008.

- “Party Leaders and Standings.” Party Leaders and Standings. Web. 30 Oct. 2015. http://www.parl.gc.ca/parlinfo/compilations/provinceterritory/PartyStandingsAndLeaders.aspx

- “REPLAY: Maclean’s National Leaders Debate.” YouTube. YouTube. Web. 30 Oct. 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hSf2__qpeGA

- Smith, Heather A. “Political parties and Canadian climate change policy.” International Journal (2008): 47-66.

- Stastna, Kazi. “How Canada’s Provinces Are Tackling Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, 15 Apr. 2015. Web. 30 Oct. 2015.

- “TVA Federal Leaders Debate: Security & Foreign Affairs.” YouTube. YouTube. Web. 30 Oct. 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOYaLI8YLSI