By Jesse Payan, Class of 2019

Introduction to Climate Finance

Since the acceptance of man-made climate change’s existence, nations around the globe have established a sense of responsibility to address the causes of climate change as well as adapt to the effects already being felt. Unfortunately, several countries have had difficulties in their attempts to accomplish the aforementioned goals. Specifically, developing nations that lack the time, resources, and money to effectively conduct research and participate in the mitigation of climate change are facing the largest problems. As a result, developing nations have begun to call on developed nations for assistance known as climate finance, which can be broadly defined as financial and technological flows from developed nations to developing nations.

What Exactly is Climate Finance?

Climate finance as defined by the World Resources Institute is as follows, “In its broadest interpretation, climate finance refers to the flow of funds toward activities that reduce greenhouse gas emissions or help society adapt to climate change’s impacts,” (Venugopal, Patel 2013). Even with these definitions being thrown around, there are still numerous different views as to what should or should not be considered climate finance. Definitions vary from what the Green Climate Fund-the green climate fund was established by the UNFCCC to assist developing nations to mitigate, as well as adapt to, the effects of climate change- can provide itself, to the total amount of climate-related flows. One thing that remains obvious, illustrated by the agreement made to drastically increase funds, is that more and more will be needed, no matter how climate finance is officially defined.

Why is Climate Finance Important?

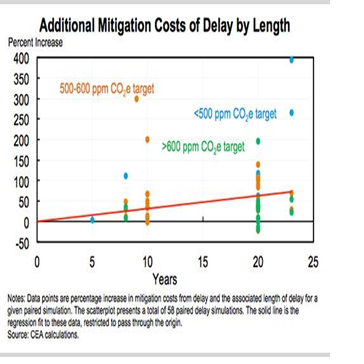

Due to the limitations in budgets of developing countries, climate finance is expected to play a key role in creating a successful global agreement in Paris when countries will be meeting for the 21st Conference of the Parties. Addressing climate change is becoming more urgent as projected costs and damages continue to rise. In the United States alone, the benefits of acting sooner rather than later range in the hundreds of billions of dollars (EPA 2015). As the effects of climate change become more prominent, developing nations are going to need more climate finance

from developed nations to effectively mitigate climate change. (Details on Figure to the Left)

What does all this mean for COP21 in Paris? For one thing, I would expect developing nations to ask developed nations for a clear timetable and outline for climate finance that will be provided in coming years. I cannot see a successful deal being struck unless progress in climate finance negotiations is made.

Climate Finance: The Goal

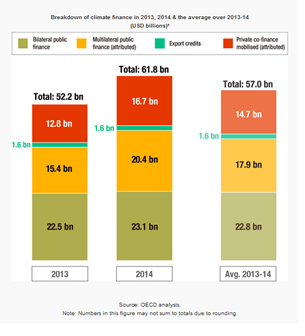

In 2009 at the 15th Conference of the Parties in Copenhagen, developed countries committed to the following goal: By 2020, 100 billion dollars in climate finance be provided to developing nations. It is important to initially point out that the goal agreed upon was quite arbitrary and was based on political reasoning rather than any scientific evidence because it highlights that we must further examine this goal throughout this paper (Cline 2011). First, it is still unclear what is considered climate finance which leads us to the question of whether or not we can achieve this goal by 2020. Next, we must address the question of more importance which is whether or not $100 billion is enough to mitigate and adapt to climate change. To do so we must analyze some recent research reports conducted and published by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, or the OECD, which recently stated that the average annual flow between 2013-2014 was $57 billion, which is pictured to the right (OECD 2015). The OECD has seen huge waves of criticism for publishing this report due to inaccuracies in reporting. Critics of this report outline that loans are included into this total number and they should not be because developed nations eventually have to pay these debts back (Williams 2015). This illustrates the importance of further analyzing this topic.

$100 Billion: Is it Possible?

In order to properly address climate change, the United Nations’ members suggested a goal of 100 billion US dollars of climate finance during COP15 in Copenhagen. In the Cancún agreement the following year, developed nations committed to the goal discussed in Copenhagen. The funds would be provided from a mixture of both public and private resources and would be regulated by the Green Climate Fund, which is the chief operating entity for mechanisms of climate finance. Upon establishment of this agreement, developing nations saw a significant increase in the average annual assistance being provided in the following few years as reported by the OECD.  Between 2013 and 2014, there was roughly a 17% increase in climate finance, increasing from US$52 billion to US$62 billion. Unfortunately, because the lack of clarity in what is to be considered climate finance, critics have made it clear that the OECD report on 2013-2014 climate finance is unreliable. This, and the fact that the current estimates of annual climate finance are significantly lower than 100 billion US dollars, raise the question of whether or not it will be possible to achieve the set goal for 2020. Several studies have been conducted by different organisations including a 2015 report by the World Resources Institute, which analyzed the projected climate finance growth in four different scenarios. Each of the four scenarios used a different definitions as to what is considered climate finance to cover most possibilities of differing definitions. If you would like to read more on these different scenarios, and I highly suggest you do as it is useful in understanding climate finance, follow this link. One of the things that seems to be consistent in each of the four scenarios is that the goal can indeed be achieved only if climate finance continues to grow annually as it has over the last few years; depending on which scenario, we will either need very rapid or steady growth (Westphal, Canfin, Ballesteros, Morgan 2015).

Between 2013 and 2014, there was roughly a 17% increase in climate finance, increasing from US$52 billion to US$62 billion. Unfortunately, because the lack of clarity in what is to be considered climate finance, critics have made it clear that the OECD report on 2013-2014 climate finance is unreliable. This, and the fact that the current estimates of annual climate finance are significantly lower than 100 billion US dollars, raise the question of whether or not it will be possible to achieve the set goal for 2020. Several studies have been conducted by different organisations including a 2015 report by the World Resources Institute, which analyzed the projected climate finance growth in four different scenarios. Each of the four scenarios used a different definitions as to what is considered climate finance to cover most possibilities of differing definitions. If you would like to read more on these different scenarios, and I highly suggest you do as it is useful in understanding climate finance, follow this link. One of the things that seems to be consistent in each of the four scenarios is that the goal can indeed be achieved only if climate finance continues to grow annually as it has over the last few years; depending on which scenario, we will either need very rapid or steady growth (Westphal, Canfin, Ballesteros, Morgan 2015).

$100 Billion: Is it Enough?

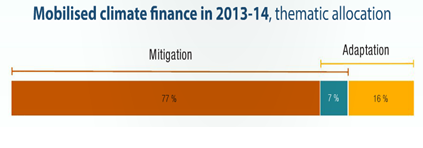

When this goal was agreed upon in Cancún, there were yet to be any technical studies on how much climate finance was necessary to mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change in the year 2020. This goes on to support the belief that the origins of this $100 billion dollar climate finance goal were purely political rather than based on scientific evidence (Cline 2011). Because the goal was politically motivated, it is no longer clear if US$100 billion is enough for developing nations to address climate change. When the Green Climate Fund was created, one of the responsibilities it was given was creating a balance in climate finance provided for mitigation costs and adaptation costs (COP15).  However, this balance does not exist. Between 2013-2014, the OECD reported(as seen above) that 77% of climate finance was for mitigation costs while only 16% was for adaptation costs and the remaining 7% was cross-cutting both sectors (OECD 2015). In 2012-2013, climate finance for adaptation reached $23-26 billion USD. Unfortunately, costs of adaptation are projected to rise up to $150 billion USD by 2025 and $250 billion USD by 2050, causing an enormous funding gap after 2020 (UNEP 2014). These figures do not take into account the climate finance necessary to achieve emission goals set in the Copenhagen Accord as well as the costs of mitigation of climate change. What we can conclude here is that $100 billion USD annually by 2020 does not seem to be enough to mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change.

However, this balance does not exist. Between 2013-2014, the OECD reported(as seen above) that 77% of climate finance was for mitigation costs while only 16% was for adaptation costs and the remaining 7% was cross-cutting both sectors (OECD 2015). In 2012-2013, climate finance for adaptation reached $23-26 billion USD. Unfortunately, costs of adaptation are projected to rise up to $150 billion USD by 2025 and $250 billion USD by 2050, causing an enormous funding gap after 2020 (UNEP 2014). These figures do not take into account the climate finance necessary to achieve emission goals set in the Copenhagen Accord as well as the costs of mitigation of climate change. What we can conclude here is that $100 billion USD annually by 2020 does not seem to be enough to mitigate and adapt to the effects of climate change.

Conclusion: Deal or No Deal

On the current pathway that we are following, we may be able to reach the goal of $100 billion USD annually in climate finance. Unfortunately, this amount does not seem to be sufficient for coming years. Unless climate finance is more strictly defined, there is a substantial increase in support being provided, and a balance between mitigation and adaptation flow is created, we are going to have a huge problem on our hands come COP21 in Paris.

Bibliography

Cline, William R. “8: Synthesis.” Carbon Abatement Costs and Climate Change Finance.

Washington, DC: Peterson Institute For International Economics, 2011. Print.

Copenhagen Accord. (COP15) “Report of the Conference of the Parties on its fifteenth session,

held in Copenhagen from 7 to 19 December 2009” 18 December 2009

EPA. 2015. Climate Change in the United States: Benefits of Global Action. United States

Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Atmospheric Programs, EPA 430-R-15-001.

M.I. Westphal, P. Canfin, A. Ballesteros, and J. Morgan. 2015. “Getting to $100 Billion: Climate

Finance Scenarios and Projections to 2020.” Working Paper. Washington, DC: WRI

OECD (2015), “Climate finance in 2013-14 and the USD 100 billion goal”, a report by the

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in collaboration with

Climate Policy Initiative (CPI).

Tirpak, Dennis, Kristen Stasio, and Letha Tawney. “Monitoring the Receipt of International

Climate Finance by Developing Countries.” Monitoring the Receipt of International

Climate Finance by Developing Countries. N.p., Aug.-Sept. 2012. Web. 13 Oct. 2015.

UNEP 2014 The Adaptation Gap Report 2014. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

Venugopal, Shally, and Shilpa Patel. “Why Is Climate Finance So Hard to Define?” Why Is

Climate Finance So Hard to Define? N.p., 08 Apr. 2013. Web. 13 Oct. 2015.

Williams, Marjorie. “A Preliminary Review of the OECD/CPI Report, “Climate Finance in

2013-14 and the USD 100 Billion Goal”” Third World Network. 30 Oct. 2015.

Web. 31 Oct. 2015