By Anne Tewksbury, Environmental Policy major, Class of 2016

The Road to Bonn

The Ad-hoc Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (ADP) is a subsidiary body of the UNFCCC tasked with the creation of a draft of legally binding international agreement on climate change action to be established by COP21 this December. From October 19-23, the delegates convened in Bonn, Germany for the eleventh part of the second session of the ADP. This was the final pre-COP negotiation, the product of which would serve as the basis for COP21. Before the meeting, the ADP Co-Chairs released a 20 page “non-paper” as a starting point for the negotiations, a condensation of the 85 page document that Parties had been working off since Lima. The goal of this session was to work off of the new draft document to emerge with a “clear, concise, comprehensive, and ambitious text” (Tubiana – ADP Opening Plenary 2015) for COP21 and most importantly, one that is able to garner “broad acceptance” from the 196 Parties involved (ADP FurtherClarification 2015).

However, the “non-paper” was not very well accepted. Co-Chair Daniel Reifsnyder stated in the opening plenary session that the Parties seemed to appreciate the “brevity, clarity, and structure” of the draft document, but the “happiness [with the text] generally stops there” (ADP Opening Plenary 2015). At less than a quarter of the length of the previous version, the draft had been slimmed down significantly. In making such substantial cuts, many ideas from the prior text were sacrificed, including climate change displacement assistance, REDD+, international air & shipping emissions, and carbon markets (Darby 2015). The draft garnered much critique from Parties and was quickly denounced as the #UStext on twitter due the perceived American bias of the content (the fact that Reifsnyder is American helped fuel the condemnation). The “non-paper” was called a “non-starter” by many Parties, some of whom refused to use it as a basis for negotiations, citing an unbalance of interests reflected in the draft which would put developing countries at a disadvantage at the bargaining table.

So What Happened?

Tensions were high as the Bonn negotiations started. In light of the discontent with the state of the draft, the ADP Co-Chairs called on Parties for suggestions of “surgical insertions” to the draft which would reflect each country or coalition’s “must-have” adjustments to the text before they were willing to use it as a starting point for negotiations. The 65 submissions received on day one spurred the Co-Chairs to come up with a follow-up draft of 34 pages, which reflected the proposals. Parties commended the acceptance of the additions, which allowed them to feel more ownership over the document, yet the text was far from complete.

For the rest of the session, delegates attended meetings of nine spin-off groups, which each focused on a different sector of the agreement (mitigation, adaptation, finance, etc.). In these groups, delegates engaged in on-screen negotiations over the content and wording of the text, adding square brackets around controversial options to designate disagreement to be resolved at a later point. The goal of these spin-off groups was to come up with streamlined text through compromise, or if an issue were too divisive, crystallize options to be evaluated at Paris. However, these sessions resulted in a 51 page compilation text with almost 1500 bracketed words, phrases, and paragraphs, indicating the Parties’ inability to reach consensus on many aspects of the draft.

[Option] Overload

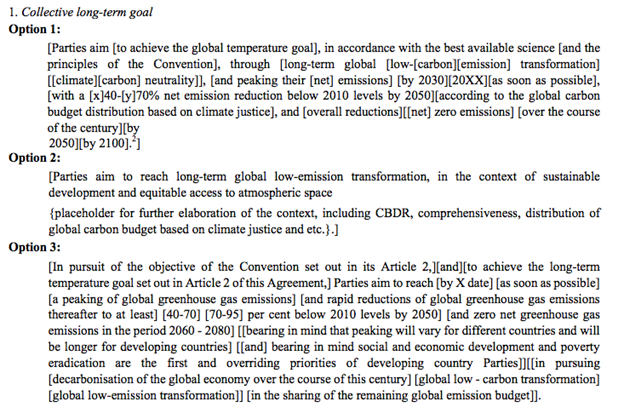

After five days of negotiations, many complex options and competing views remained in the document. Entire sections exist within brackets, including the controversial Loss and Damage portion. Further, the number of options available often prohibit any sense of direction for the text. For example, the collective long-term goal for mitigation, meant to shape the entire agreement by implementing an overarching target for emissions reductions, contains so many bracketed options that the Parties may as well be starting from scratch in Paris.

Obviously, the “brevity, clarity, and structure” of the original non-paper have disappeared almost entirely. Three options, lots of brackets, and placeholders, all in the construction of a single sentence, create nothing more than vague framework for a goal that has yet to be determined. A hodgepodge of possibilities remain in this compilation, which is supposed to be the guiding principle for the mitigation efforts. The issue of mitigation is essential to the entire agreement: stabilizing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere to a safe level is a primary goal for COP21. The current state of the section is not conducive to settling an agreement. With so many options, delegations can become so attached to particular ideas or phrasings that they lose sight of the compromise that will be necessary for consensus. When that happens, the negotiation shifts from being compromise-oriented to a “zero-sum” game, where Parties view protecting their own proposals as more important than reaching agreement (Chasek et al., 2015). With the multitude of options present throughout the document in its current state, Paris will challenge Parties to hold the vision of a globally acceptable treaty as more valuable than the pursuit of individual interests.

Moving Forward in Paris

UNFCCC Executive Secretary Christiana Figueres proclaimed at the closing plenary of the October meeting, “We now have a Party-owned text that is balanced and complete. The challenge for governments is to bring it down to a much more concise and coherent form for adoption in Paris.” Although it is not anyone’s ideal text, the new draft encompasses the perspectives of all the Parties, making it a solid baseline for productive negotiations. Now that all of the options are present in the text, Parties need to be ready to step back and bargain, even though that will require sacrificing some of the proposals they worked so hard to get into the document. Ambassador Laurence Tubiana of France warned that unwillingness to compromise, while prevalent in Bonn, will not be conducive to success in Paris (ADP Closing Plenary 2015).

On November 30, Parties are meeting again as they convene for COP21. The UNFCCC secretariat was tasked with streamlining the current draft to correct for duplication and repetition. This edit was purely editorial, with no changes made to the content of the document (which can be found here). Parties have been encouraged to embrace the “spirit of compromise” as the final round of negotiations start (Tubiana – ADP Closing Plenary 2015). Copious options have been put on the table, and now delegates will have to prioritize among their positions in working toward a consensual text as the document is inevitably slimmed down once again. Predictions are being made for the outcome of Paris, and whatever the resulting agreement, difficult decisions will have to be made. It is said that a good compromise leaves everyone unhappy, and it looks like COP21 will be no exception.

Bibliography

Pamela Chasek, Lynn Wagner, I. William Zartman. “Six Ways to Make Climate Negotiations More Effective.” Centre for International Governance Innovation. June 2015

Lawrence E. Susskind and Saleem H. Ali. Environmental Diplomacy: Negotiating more Effective Global Agreements. New York. Oxford University Press. 2015

Ariel M. Hernandez. Strategic Facilitation of Complex Decision-Making: How Process and Context Matter in Global Climate Change Negotiations, Cham. Springer International Publishing. 2014

Scott Barrett. Environment and statecraft : the strategy of environmental treaty-making. New York. Oxford University Press. 2003

Pamela Chasek. Earth negotiations : analyzing thirty years of environmental diplomacy. New York. United Nations University Press. 2001

Megan Darby. “UN releases 20-page negotiating text for climate deal.” Climate Home. October 2015. http://www.climatechangenews.com/2015/10/05/un-releases-20-page-negotiating-text-for-climate-deal/

Laurence Tubiana, “Plénière ADP–Intervention de LT,” ADP 2-11, Bonn, October 19, 2015

https://unfccc.int/files/meetings/bonn_oct_2015/application/pdf/lt_20151019_statement.pdf

ADP 2-11 Opening Plenary Webcast. UNFCCC. October 2015. http://unfccc6.meta-fusion.com/bonn_oct_2015/events/2015-10-19-10-00-ad-hoc-working-group-on-the-durban-platform-for-enhanced-action-adp

ADP 2-11 Closing Plenary Webcast. UNFCCC. October 2015. http://unfccc6.meta-fusion.com/bonn_oct_2015/events/2015-10-23-09-02-adp-closing-plenary

Earth Negotiations Bulletin. “Summary of the Bonn Climate Change Conference” Volume 12 Number 651. October 2015. http://www.iisd.ca/vol12/enb12651e.html

Eco. “Eco 5, ADP 2.11 Bonn October 2015 – PAMAMP Issue.” October 2015. http://www.climatenetwork.org/sites/default/files/eco_5_adp2-11_english.pdf

Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action. “Non-Paper.” UNFCCC. October 2015. http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/adp2/eng/8infnot.pdf

Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action. “Scenario Notes” UNFCCC. October 2015. http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/adp2/eng/8infnot.pdf

Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action. “Further Clarification on the Initial Mode of Work at ADP 2.11” UNFCCC. October 2015. https://unfccc.int/files/bodies/awg/application/pdf/further_clarification_note_mode_of_work_adp_2_11.pdf

Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action. “Draft agreement and draft decision on workstreams 1 and 2 of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action” (Advance Unedited Version). UNFCCC. October 2015. http://unfccc.int/files/bodies/application/pdf/[email protected]

Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action. “Draft agreement and draft decision on workstreams 1 and 2 of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action” (Edited Version). UNFCCC. November 2015.

http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/adp2/eng/11infnot.pdf